Scientist of the Day - Karl Popper

Karl Raimund Popper, an Austrian/English philosopher of science, died Sep. 17, 1994, at the age of 92. Popper was born in Vienna on July 28, 1902, into an artistically and academically distinguished and former Jewish family. He had an odd education for a future philosopher, “attending” school long before enrolling in it, supporting himself as a carpenter and a teacher. Vienna was the home of a school of philosophers called the "Vienna Circle," who espoused a brand of philosophy they called logical positivism, which we will return to in a moment, and Popper was certainly exposed to the influential Circle during his years there. He also dabbled in psychoanalysis and was enthusiastic toward Marxism, until a number of his friends were killed in a protest. He eventually received a degree, and sensing the way the German wind was blowing, he looked to leave Austria. He spent several years studying in England, casting about for a new job, and eventually found one in New Zealand, where he taught for a while before moving to London for good. He eventually became professor of philosophy at the London School of Economics.

Now back to the Vienna Circle and logical positivism, with which Popper would take great exception. The logical positivists believed that science progresses by induction, reasoning logically from fact gathering and experimentation to the formulation of hypotheses for further experimentation and verification. Verification was a big deal to the positivists. Those hypotheses that were verifiable in some way proved themselves better than those that were not, and were adopted, leading to new hypotheses.

Popper would have none of this induction nonsense and the idea of verifiability. He proposed instead that a scientific theory should be measured by its "falsifiability" – its potential for being proved wrong. If it were possible to refute a hypothesis, and it was not refuted, then that was strong support for the truth of the hypothesis. The statement “All crows are black” can never be truly verified by induction, but it can easily be falsified by finding a single white crow; the fact that we have not found a white crow is evidence for the truth of the statement.

Philosophers of science at the time (and I suppose still) were also concerned with the "demarcation problem" – how does one distinguish science from pseudo-science? Popper argued that falsifiability would help us weed out pseudo-sciences, which were often based on assumptions that could not be proved or refuted. If a theory was not falsifiable, said Popper, it was not a scientific theory. Two examples he often used were astrology and psychoanalysis. Since psychoanalysis had explanations for everything, and no statement could be refuted, it was no science, for Popper.

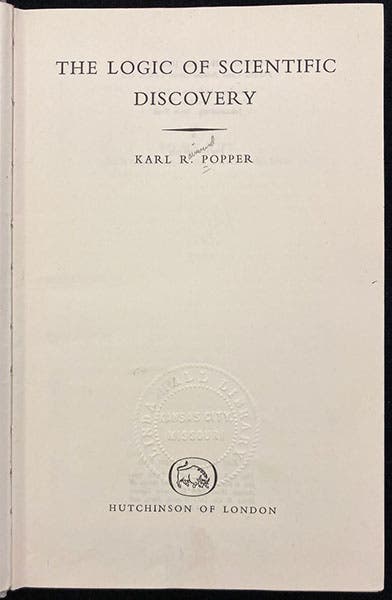

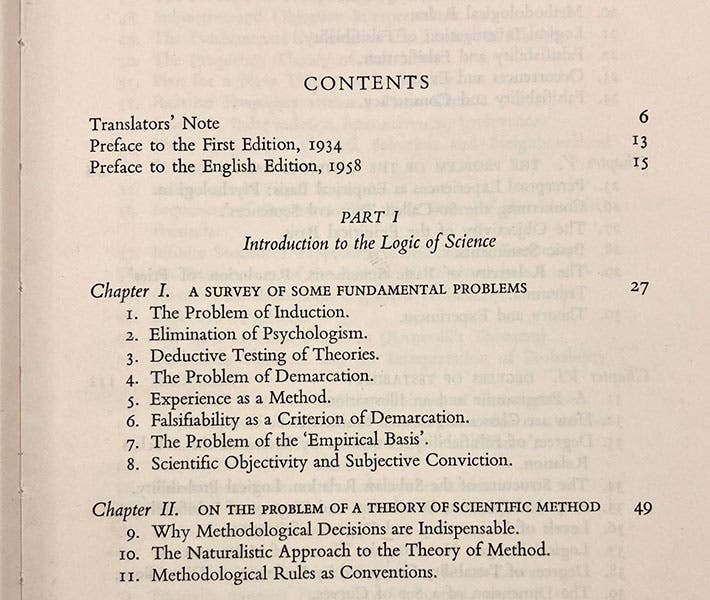

Popper published two books, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959), and Conjectures and Refutations (1962), which argued for his doctrine of falsification. The first book was originally written in German in 1934 but only a condensed version was published at the time. Popper himself translated the book into English for the 1959 publication.

The second book came out the same year as Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), which would alter the whole debate by challenging the assumption (common to both Popper and the Vienna Circle) that science was a slow, cumulative process that advanced by rational choice between theories. Kuhn argued that most scientists practiced what he called “normal science,” the gathering of facts and details to flesh out the reigning “paradigms,” and falsifiability played little role in normal science. We will defer further discussion of the difference and disagreements between Popper and Kuhn until we have a chance to write a post on Kuhn.

Queen Elizabeth didn’t care what Kuhn said. She knighted Sir Karl in 1965, and he remained intellectually active until his death in 1994. A discussion of falsifiability has a place in every philosophy of science textbook published since the 1960s.

My favorite falsifiability story actually predates The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Wolfgang Pauli, the German pioneer in quantum theory, was brutally intolerant of shoddy science. The story is often told that Pauli, presented with a paper proposing some pseudo-scientific nonsense, said of it: “That is not only not right, it is not even wrong!” If it can't be falsified, it is not science. One would presume that Popper understood and agreed with Pauli's reaction.

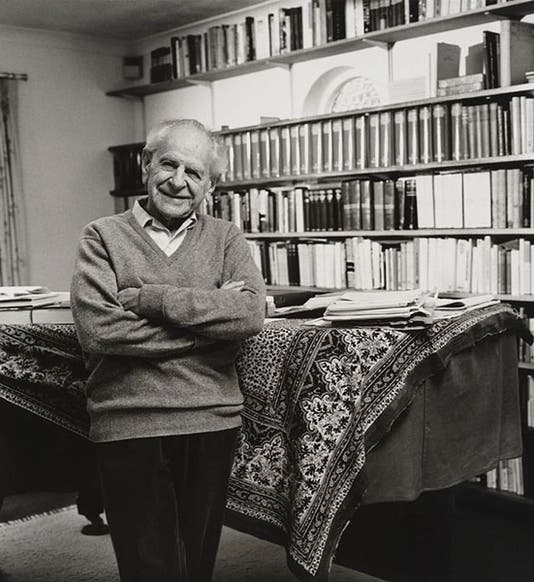

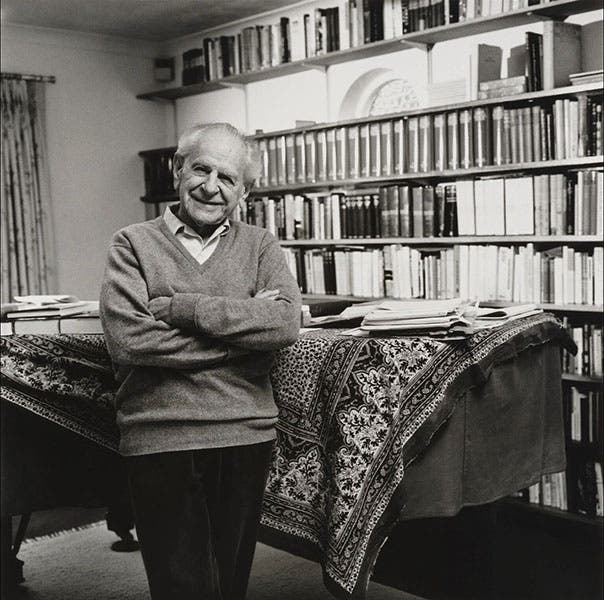

For some reason, there are few photos in circulation of Popper as a young or even a middle-aged philosopher. But then, he was old for over 40 years. My favorite is a photo by Lucinda Douglas-Menzies, taken in 1988, when Popper was 86 years old, and now in the National Portrait Gallery, London (first image).

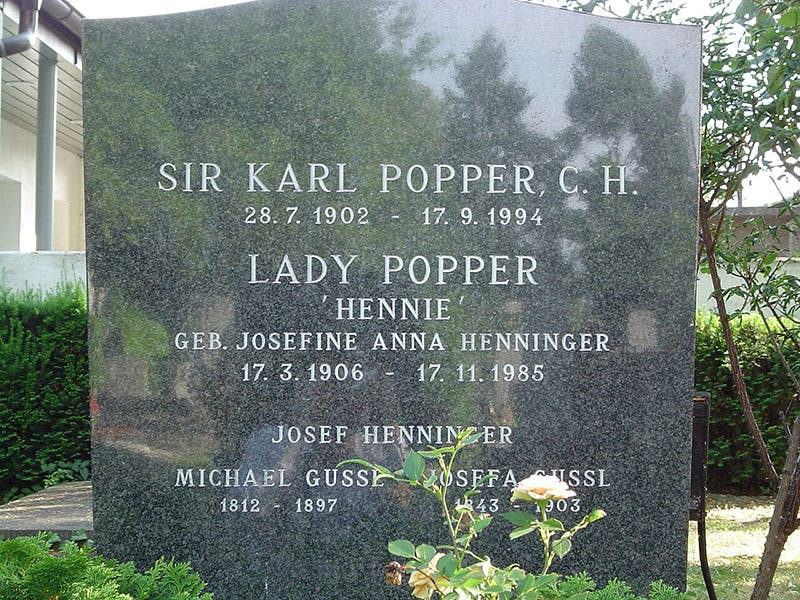

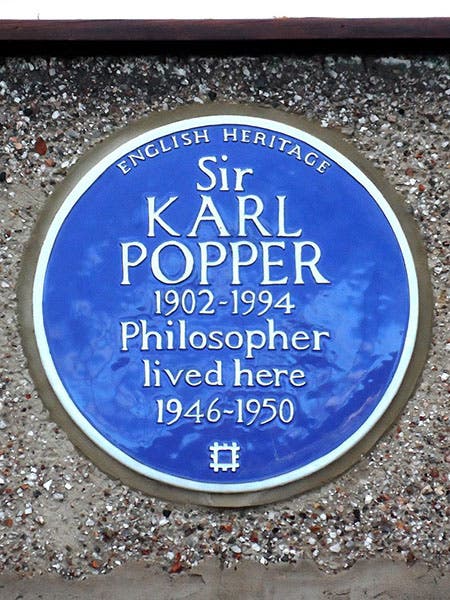

Popper is buried alongside his wife in Lainzer Friedhof, just outside Vienna (fifth image). There is a blue plaque in London at the site of one his residences (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.