Scientist of the Day - Karl Cäsar von Leonhard

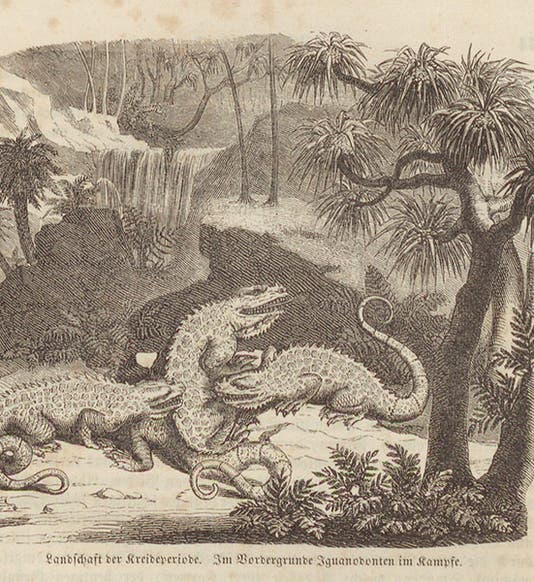

Battling Iguanodons, wood-engraved headpiece, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 2, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, a German geologist, was born Sep. 12, 1779. If Leonhard had any formal training in geology, I was unable to piece it out, but he came from a well-to-do family, so he travelled, and collected minerals, and wrote several treatises on minerals, and managed to get himself appointed to the chair of mineralogy at Heidelberg in 1818. He translated two geological works by Alexander von Humboldt for publication in 1823 (we have both in our collections), and seems to have favorably impressed Humboldt and other prominent German geologists. Leonhard was initially partial to the geological philosophy of Abraham Gottlob Werner (also an eminent mineralogist), who taught that all rocks, including basalt and granite, had an aqueous origin, and were not igneous in nature. Leonhard came to disagree with this notion, and he published in 1832 a treatise called Die Basalt-Gebilde (Basalt Formations), in which he described and illustrated a variety of basalt intrusions in rock formations all over Europe. The hand-colored engravings of these intrusions are quite lovely, and we displayed the work in our exhibition, Vulcan's Forge and Fingal's Cave: The Discovery of Geologic Time (2004). You may see the entry on Leonhard, with one of his colored diagrams, at this link.

Portrait of Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, lithograph, by Rudolf Hoffmann, ca 1860, Austrian National Library, Vienna (Wikimedia commons)

Leonhard published several influential works on geology in the 1830s and 1840s, and he co-edited an important journal, Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie and Paläontologie, beginning in 1830, all of which we have in our history of science and serials collections. But we are going to skip ahead to one of his last works, published when he was 76 years old, because it is such a wonderful example of how to write and illustrate a work of popular science and make it inviting to the reader.

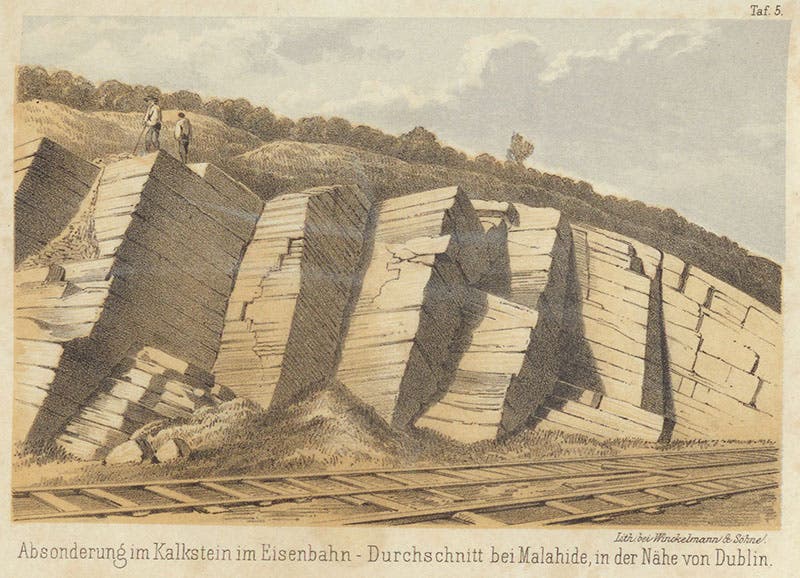

Limestone strata at a railroad cut near Dublin, tinted lithograph, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 1, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

The book is called Das Buch der Geologie. It is in two small volumes, although our copy has the two bound as one. All the images we show here, except for the portrait, come from this work. There are three kinds of illustrations: hand-colored lithographs, usually as frontispieces or inserted plates; engraved headpieces and tailpieces, which serve to make the book attractive; and text woodcuts, which illustrate the text. We include all three kinds. For a sample color lithograph, we chose one that shows the limestone strata left in the wake of a railroad cut outside Dublin (third image). Leonhard also included lithographs of basalt formations on Teneriffe; a waterfall in Newfoundland; and more.

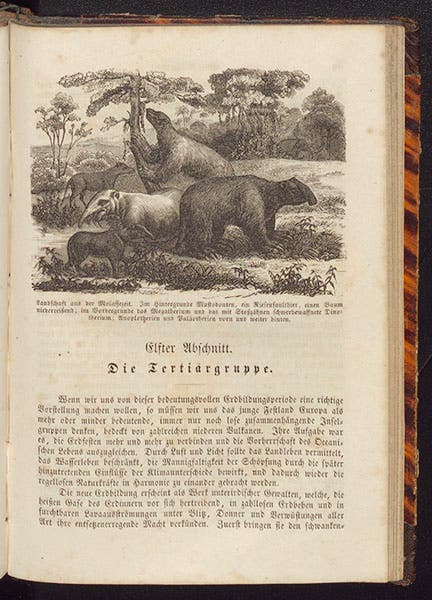

Megatherium, Deinotherium, and other Tertiary mammals, wood-engraved headpiece, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 2, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

The headpieces are especially dramatic, and we show two of them: one full-page, so that you can see that it is indeed a headpiece, depicting a variety of extinct Tertiary mammals, including a giant ground sloth and a Deinotherium (fourth image); and a second, in detail, dramatizing a trio of battling Iguanodons, which was a favorite theme of book illustrators, even though Iguanodons did not engage in such public displays of disaffection (first image). For a sample tailpiece, we show one that illustrates a glacial table – a rock, formerly lying on a glacier, which has been left in a precarious position by the melting of the glacier (fifth image). In this case, we know what inspired the illustrator, since James Forbes had published this very image in a travel book of 1843, which we illustrated in a different exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance (2008).

Glacial table, wood-engraved tailpiece, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 1, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

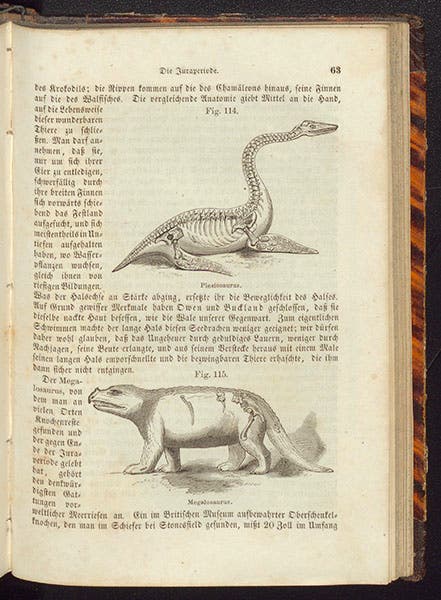

Plesiosaurus and Megalosaurus, text woodcuts, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 2, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

As a sample of the text woodcuts, we show a page with pictures of a restored Plesiosaurus and a restored Megalosaurus – the latter especially timely, since it had just been published the year before by Richard Owen in a book describing the Crystal Palace in London, which we also displayed at one time, in our exhibition Paper Dinosaurs; you can see Owen’s restoration here. The fact that many of Leonhard’s illustrations were borrowed from other books is not a criticism – that is how you illustrate textbooks – but in this case, a point of praise, since not many textbook writers are aware of professional publications that appeared just the previous year. It is interesting, by the way, that Leonhard included so many pictures of prehistoric animals – he was not a paleontologist. But he knew what interested the general reader.

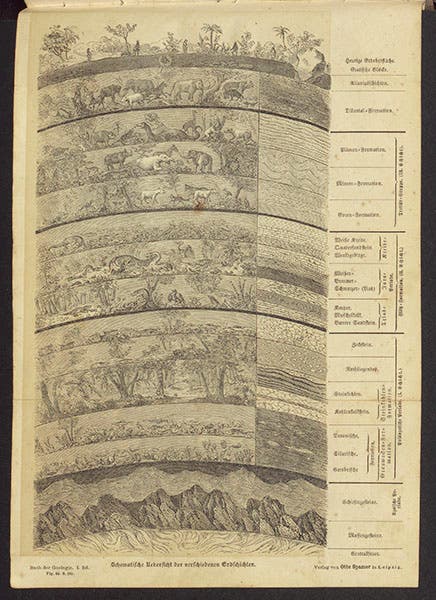

Geological section with added prehistoric scenes, folding woodcut, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 1, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

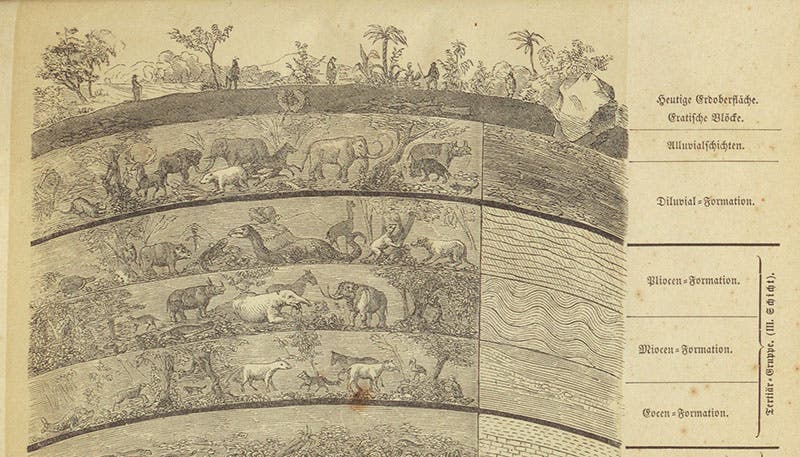

It is hard to categorize our last example from Leonhard’s book, since it is so unusual. It is a large folding woodcut (seventh image). It is captioned: “Schematische Übersicht der verschiedenen Erdschichten” (“Schematic overview of the different layers of the Earth”). The right side shows a geological section, and this is conventional in geology textbooks, with the present-day Earth at the top, and the Tertiary, Secondary, and Primary formations descending below – a section through time, if you will. The unusual part is on the left, where we see recreated scenes of the animals and plants that lived on Earth at the time that the corresponding rock formations, like the Jurassic, were being deposited. We include a detail of the top third of the woodcut, showing the Tertiary scenes, below (eighth image). Such an illustration is not unprecedented, but I have never seen it done like this, with so much detail, and for the entirely of Earth history. It seems to be original. Perhaps Leonhard borrowed it from some previous work, but if so, it is unknown to me.

Detail of seventh image, 5 scenes of prehistoric life, from present-day at top down to the Eocene, Karl Cäsar von Leonhard, Das Buch der Geologie, vol. 1, 1855 (Linda Hall Library)

Leonhard died in 1862, having been made a Teutonic knight at some point, since the word “Ritter” (knight) accompanies his name on the title page of Das Buch der Geologie. We have a portrait of a young Leonhard that served as a frontispiece to another of his books in our library, Charakteristik der Felsarten (1823), but he looks positively fierce in that engraving, so I will reserve it for another time. I show instead an engraving of an older and kindlier Leonhard, which seems appropriate to accompany a post about a book written when he in his twilight years (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.