Scientist of the Day - Jules Verne

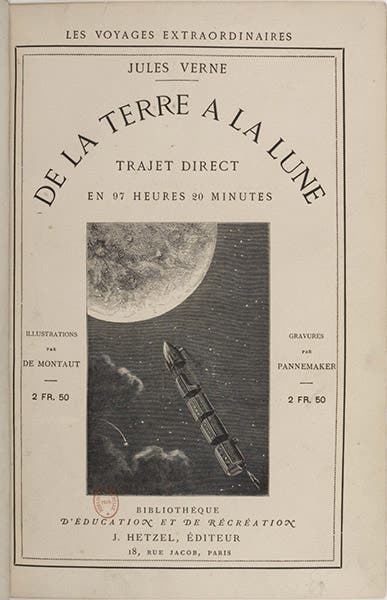

Title page with wood-engraved vignette, De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

Jules Verne, a French popular writer and novelist, was born Feb. 8, 1828. Verne has been called the father of science fiction (unless you prefer to confer that honor on Edgar Allan Poe, or perhaps Mary Shelley), and indeed many later science fiction authors, such as H.G. Wells, do seem to have taken their inspiration from Verne. His first popular work was Voyage au centre de la Terre (Journey to the Center of the Earth), 1864, followed by De la Terre à la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon), 1865; Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea), 1869; Autour de la lune (Around the Moon), 1870, a sequel to From the Earth to the Moon, and Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingt jours (Around the World in 80 Days), 1873. These formed part of a series that his publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, called Voyages extraordinaires, and which would eventually extent to over 50 volumes, with a dozen more that were unpublished until after Verne’s death. Nearly all of Verne's novels were translated into English, and nearly all were accompanied by text illustrations by well-known artists and wood engravers, and which played no small role in the popularity of Verne's books. The fact that you probably recognize the titles of all five books we have mentioned so far is a testament to both his popularity and his influence, then and now.

We have written posts on three of Verne's artists: Edward Riou, who illustrated Journey to the Center of the Earth; Emile-Antoine Bayard, who illustrated Around the Moon, and Alphonse de Neuville, who, with Riou, did the wood engravings for Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. However, except in the case of Neuville and Twenty Thousand Leagues, we haven't really engaged with any of Verne's tales. We are going to do so today with From the Earth to the Moon, which I reread for the occasion, and which I enjoyed much more than I expected I would.

Artillerymen of the Baltimore Gun Club, victims of their profession, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

Impey Barbiicane, president of the Baltimore Gun Club and mastermind of the lunar projectile project, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

The tale begins with the Baltimore Gun Club, made up of artillerymen and cannoneers, who reveled in deploying their armament during the Civil War but who were now (1865) in a state of personal crisis, with nothing to blow up. The members are caricatured by Verne, described as armless and legless, and missing other body parts, a result of cannon catastrophes and mortar mishaps. The President of the club, Impey Barbicane, conceives a grand idea of building a huge cannon to send a projectile to the Moon. The entire Gun Club is wildly enthusiastic about the plan. In typical Vernean fashion, the reader is treated to lots of plausible physics, deriving the speed a projectile would have to reach to escape the Earth, and demonstrating that such a projectile would have to be launched somewhere below the 28th parallel to have a chance of impacting the Moon. Since it is shown that the projectile would have to be fired vertically, that means the cannon will have to be buried in the ground, and since it will have to be 900 feet long to provide the desired impetus, that means digging a huge hole somewhere below the 28th parallel.

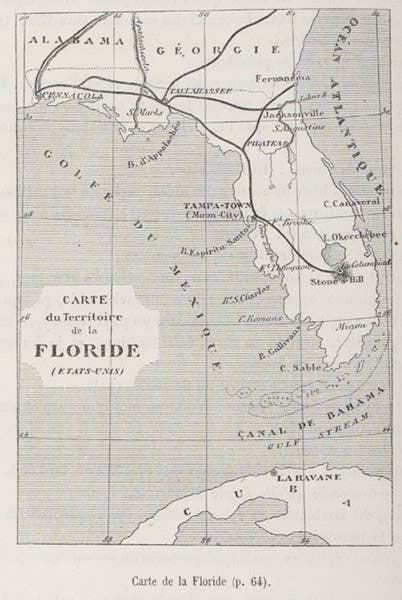

Map of southern Florida and the location of the cannon well at Stone Hill, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

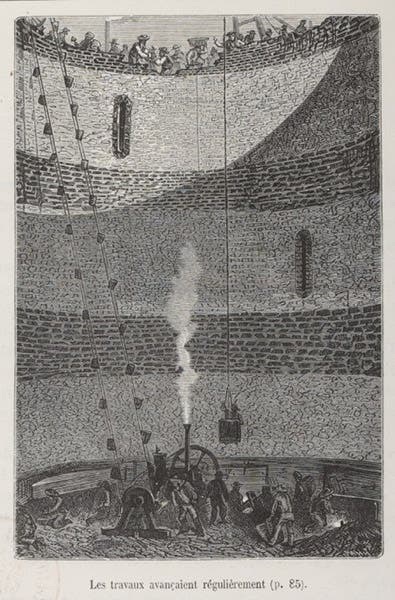

The leaders set out for Florida, with Barbicane in charge; they land in Tampa, at the time a backwater town, and proceed to search for a spot at least 900 feet above sea level, which they find at a place called Stone Hill. A crew is hired and digging begins at once (sixth image). The well has to be some 60 feet wide to accommodate the stone lining that will act as the mold for the cannon, which will be poured on site from 1200 foundries built to circle the site. All of this activity is described in graphic detail, and, I must say, the account is most thrilling, especially on the day of the “grand pour”, when all that molten iron flows down into the mold.

Digging the masonry well for the mold for the 900-foot cannon, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

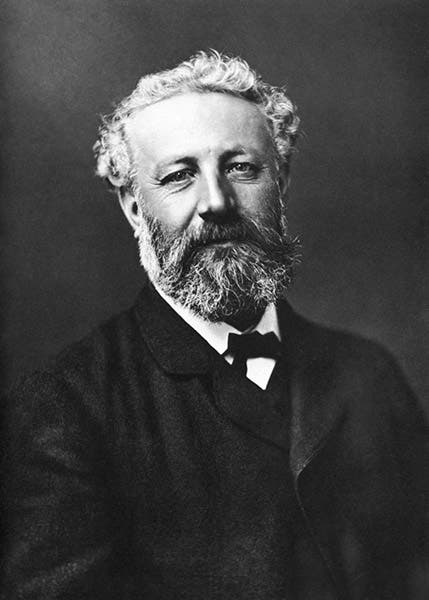

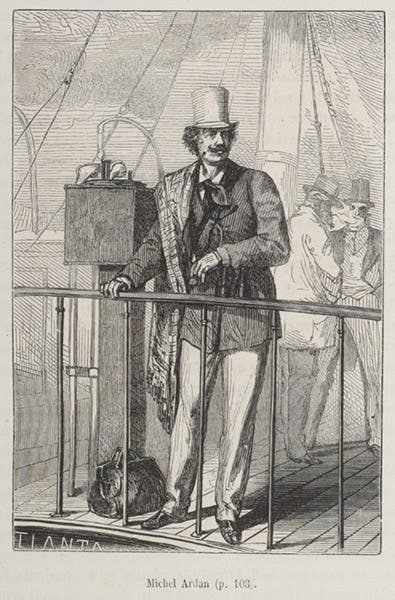

Meanwhile, Barbicane has learned that a Frenchman, Michel Ardan, has declared that he intends to ride inside the projectile to the Moon and has boarded a steamer for Florida. Barbicane is at first flummoxed, then irritated, but when Arman arrives, the two hit it off, and Barbicane agrees to the new plan, and orders a modified projectile that can hold a human passenger (as it turns out, several passengers). Ardan is a very sympathetic and attractive figure, heroic like Barbicane but of a different character, much more laid back. He is said to have been modeled on Nadar, the noted French photographer and adventurer (who will later photograph Verne, second image).

Michel Ardan, the Frenchman who volunteers to ride in the projectile to the Moon, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

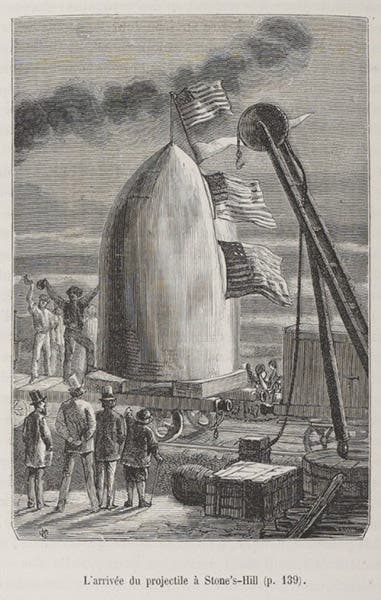

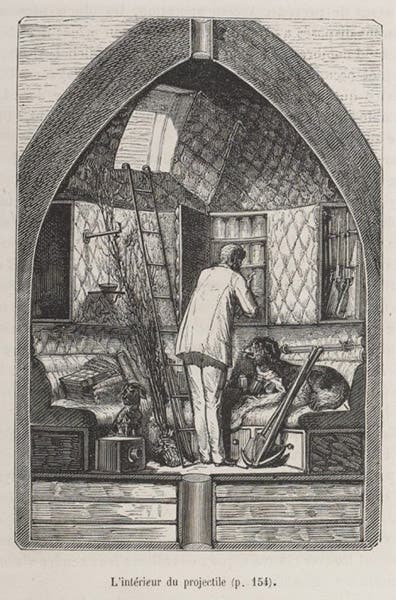

The projectile arrives at Stone Hill, and Ardan takes over the interior decorations (eighth and ninth images). It is finally agreed that the capsule will carry three passengers: Ardan, Barbicane, and a Captain Nicholl, whom we encountered by name, earlier in the book, as the principal critic of Barbicane’s scheme, and who shows up in person in Florida to challenge Barbicane, and then becomes part of the adventure.

The steel projectile arriving at Stone Hill, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

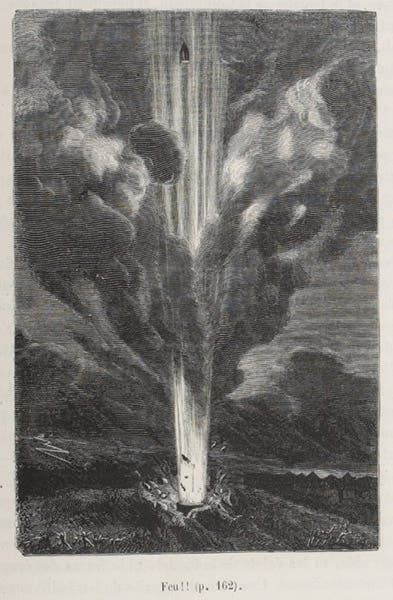

The launch occurs on schedule, as the 400,000 pounds of guncotton at the bottom of the cannon-barrel is electrically detonated, and the explosive force not only launches the capsule but lays waste to much of the countryside, leaving us to wonder how anyone survived inside the steel shell (tenth image). Barbicane had encouraged the Harvard College Observatory (here called the Cambridge Observatory) to build a huge telescope on Long’s Peak in Colorado to monitor the projectile’s path to the Moon, but the cannon fire produced so much smoke that the atmosphere was obscured for many days, even in Colorado. Finally, when the smoke clears, the fate of the launch is revealed. We are not going to tell you what that fate it, because you might want to read the book and have some suspense left in store. But the fact that there was a sequel, in which the astronauts are returned to Earth, tells us that whatever ensued, it was not disaster.

The projectile fitted out by Michel Ardan for the 97 hour journey to the Moon, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

If I had read From the Earth to the Moon in 1866, I think I would have been very excited and entertained. I would have felt scientifically educated as well, since Verne went to great lengths to show why certain things are possible, and others are not. The book incorporated recent scientific developments and discoveries, which makes it feel very current; for example, Barbicane learns about Ardan from a message than came over the new trans-Atlantic cable, which was laid the very year the book was written.

The projectile being fired toward the Moon from the underground cannon at Stone Hill, wood engraving after a design by Henri de Montaut, in De la terre à la lune, by Jules Verne, 1865, here from the 1868 ed, Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

Finally, we should mention the wood-engravings, 9 of which (out of 41) we have incorporated into this post. They were drawn by Henri de Montaut and are just delightful. I especially like the one that shows some of the leading members of the Baltimore Gun Club, with their assortment of artificial legs and hooks for hands (third image), and the one that depicts the newly decorated projectile, complete with dog (ninth image). I do have to comment on the title-page vignette, since it is the one most often reproduced (first image). It first appears in chapter 19, “A Meeting”, where it illustrates Ardan’s vision of space travel, as he explains to Barbicane and a large crowd that one day there will be “trains of projectiles” ferrying people to and from the Moon. The woodcut spawned by this prophecy was so magnificent that it was chosen to go on the title page. But it does not depict anything that happens in the book; it is not the projectile within which Barbicane and his companions travel to the Moon.

We will return to Verne one day, because we haven’t really come to grips with the question of what kind of science writer Verne was. Was he indeed a science fiction author? Or was he something different entirely? We might also wonder why he has continued to be so popular over a century after his death. And speaking of death, we have yet to show you his amazing tombstone. That should tantalize you enough to bring you back for the sequel.

If you were wondering, we do not have any works by Jules Verne in our library, as he is at present considered out of scope. It would be nice, in my opinion, if collection guidelines were broadened enough to include him.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu