Scientist of the Day - Jules Lissajous

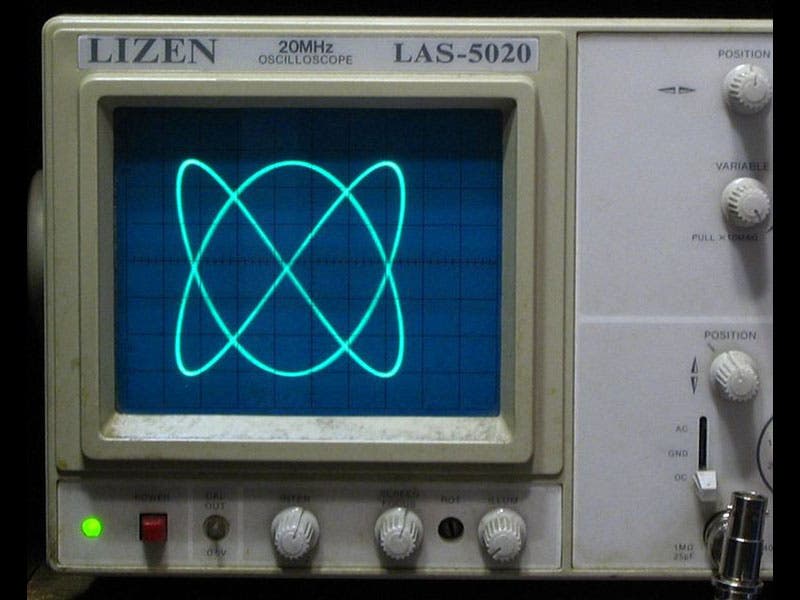

Jules Lissajous, a French mathematician, was born Mar. 4, 1822. If you have ever watched older submarine or science fiction movies that involve personnel looking at oscilloscopes or cathode ray tube (CRT) screens, you have probably noticed that the screens typically show revolving patterns of circles, hourglass figures, or changing sine waves (second image above). These are called Lissajous figures, and they were invented by our honoree back in 1855. Lissajous figures are regularly used by movie makers whenever CRTs are visible, because they are pretty, and they move around in an attractive manner, even if they are the last thing you would see on a radar screen if you were looking for enemy submarines. But there were no CRTs in 1855, so what exactly did Lissajous invent?

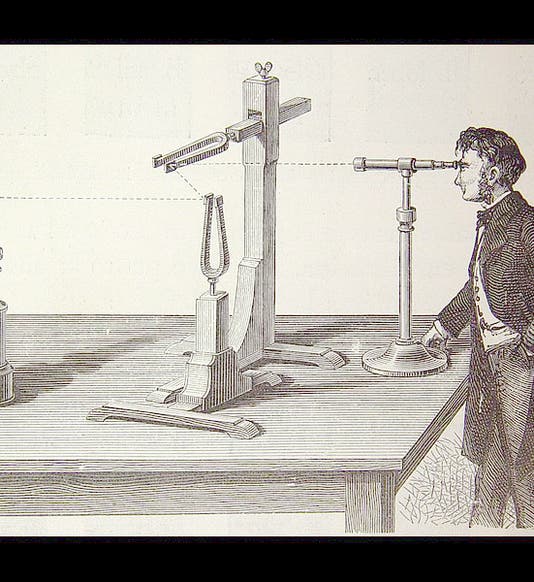

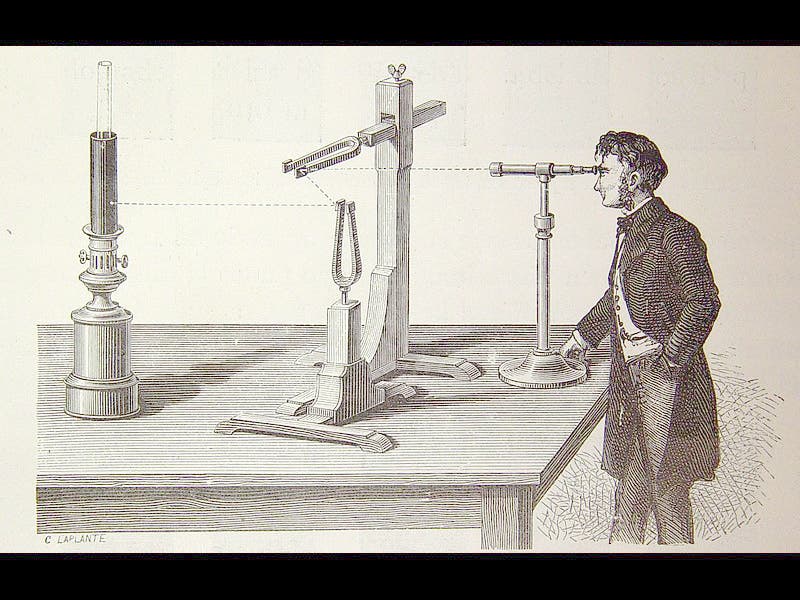

Lissajous was working with sound waves-- with sound produced by tuning forks, to be specific. He discovered that if you attach a tiny mirror to a tuning fork, and bounce a light beam off it and onto the wall, you get a visual display of the vibration (a sine wave, in fact, just like on the oscilloscope). And then he found that if you reflect the light from the first fork onto a mirror on a second tuning fork, tilted 90ᵒ to the first, and then onto the wall, you get something quite different--a perfect circle. That would have been the case if the two forks were identical in frequency. But if one vibrated a little faster than the other, then the circle would oscillate, becoming an ellipse, a diagonal line, an ellipse again, and then back to a circle. This was the first Lissajous figure (see first image; the figure in the illustration is actually Lissajous himself, and he views his figures with a microscope, instead of projecting them on the wall). If the frequencies are double or triple one another, you get entirely different figures, and if the frequencies are not exactly even multiples, the figures will rotate slowly or oscillate. The third image shows just a few of the thousands of possible Lissajous patterns.

In the last half of the 19th century, instrument makers had a field day inventing demonstration devices to generate Lissajous figures, using either tuning forks, as Lissajous did, or pairs of pendulums swinging in different planes, which, if attached to pens, will produce complicated Lissajous patterns on paper. With the invention of the CRT in the early 20th century, these ingenious demonstration devices disappeared. Fortuntely the name of Lissajous lingers on as a descriptive adjective.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.