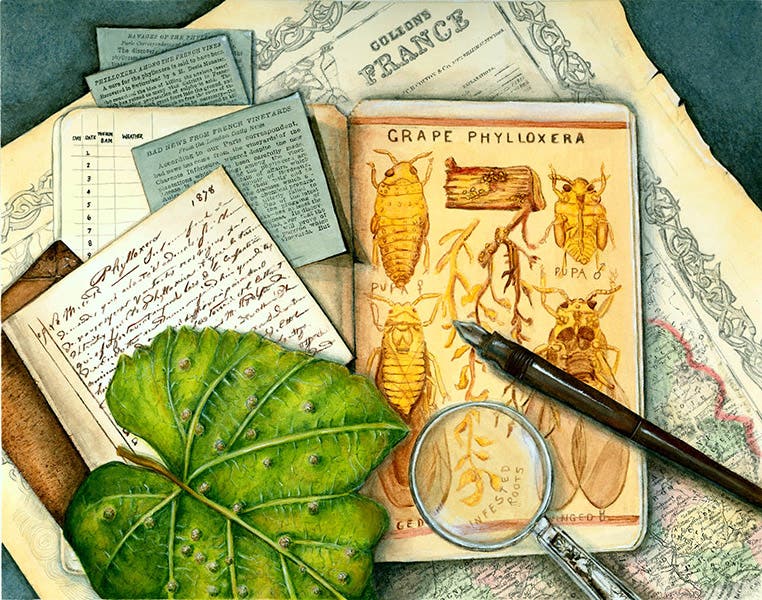

Scientist of the Day - Jules-Émile Planchon

Jules-Émile Planchon, a French botanist, was born Mar. 21, 1823. Planchon was professor of botany and pharmacy at the University of Montpellier in southern France. In 1866, French grape vines in the wine-growing regions along the Rhone River began to mysteriously wither and die. The maladie spread rapidly and sent shudders through vine owners and wine drinkers alike. The cause was not apparent from inspection of the dead plants. So Planchon was called in as part of a three-man commission in the summer of 1868.

Planchon and his team got no answers from the dead plants, but on inspecting live vines nearby, they found that the roots were infested with microscopically tiny yellow aphid-like insects. This root-louse, which the French called a puceron, and which Planchon assigned to the genus Phylloxera, was deemed by Planchon to be the cause of the blight.

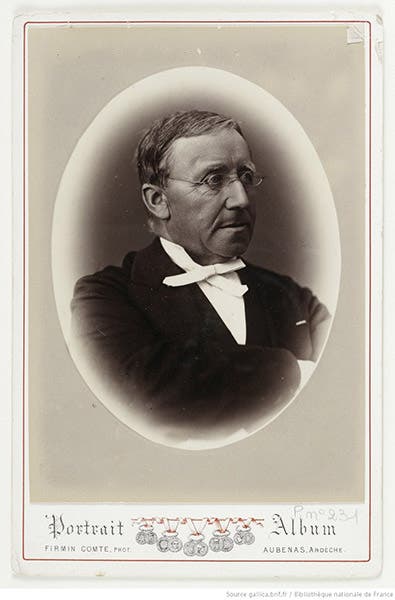

Amazingly, the scientific establishment resisted this interpretation, insisting that the lice were a symptom and not a cause – that Phylloxra attacked only plants that were already sick, and that the true cause lay elsewhere – in the soil, or in the weather, or in mistreatment of the vines. Planchon had to fight long and hard to prove that Phylloxera was the cause of the disease and not an after-effect. Planchon was visited in the early 1870s by an American entomologist, Charles V. Riley, from whom he learned that Phylloxera was common in the United States, but that American vine-roots were resistant to the louse. After making a trip to the United States in 1873 to inspect American vineyards and consult further with Riley in St. Louis, Planchon recommended that certain American vines be imported to France, not to provide the grapes (Dieu nous en préserve!), but to serve as rootstocks on which French vines could be grafted. Since Planchon had also discovered that Phylloxera crept into France from the United States in the first place, it was only fitting that America should provide the cure for the disease they inflicted on France. A grafting program was begun, and by the time of Planchon's death in 1888, the French wine industry had been saved, and Vincent Van Gogh could portray the vineyards around Arles, where the French infestation had begun 22 years earlier, as a thriving enterprise (third image).

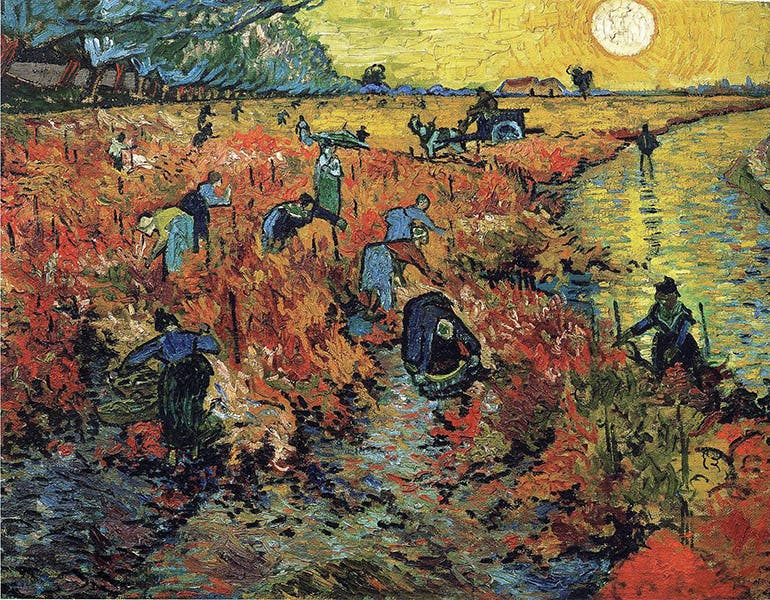

Planchon is still a hero to winegrowers in France, especially in his home city of Montpellier, where they erected a monument to him in a city park in 1894 (fourth image). Planchon is the bust at the top; the other stone figure is an appreciative vigneron or vineyard worker.

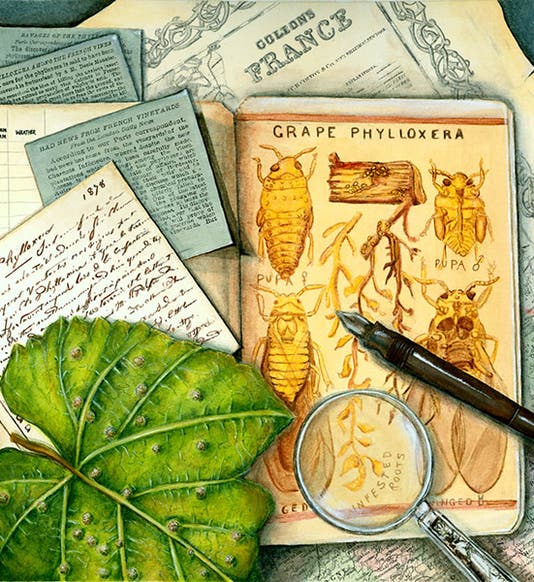

The story of the French battle with Phylloxera has been told several times; our favorite book is Dying on the Vine: How Phylloxera Transformed Wine (2011), a lively, well-written account by George Gale, a retired philosopher of science and a former colleague of mine at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Our opening image is a gouache by Melisa Beveridge, who utilized many artifacts of the battle with Phylloxera, including a painting of grape Phylloxera by Riley, which is still in the archives of the Department of Entomology at Kansas State University. We showed several others of Riley’s paintings at our post on Riley. Ms. Beveridge’s painting was used as the dust-jacket art for Professor Gale’s book. You may see more of her natural history illustrations at her website.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.