Scientist of the Day - Josiah Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs, an American physical scientist, was born Feb. 11, 1839. His name is often unrecognized by the public, yet Gibbs was unarguably the greatest scientist America produced up through the end of the 19th century, and perhaps beyond. His field was thermodynamics, which might explain the poor name recognition, except that we recognize other workers in that field, such as James Joule, James Clerk Maxwell, and Lord Kelvin. Perhaps it is the mathematical nature of Gibbs’ work, and the fact that he cared little for self-promotion, that explains his low threshold of visibility.

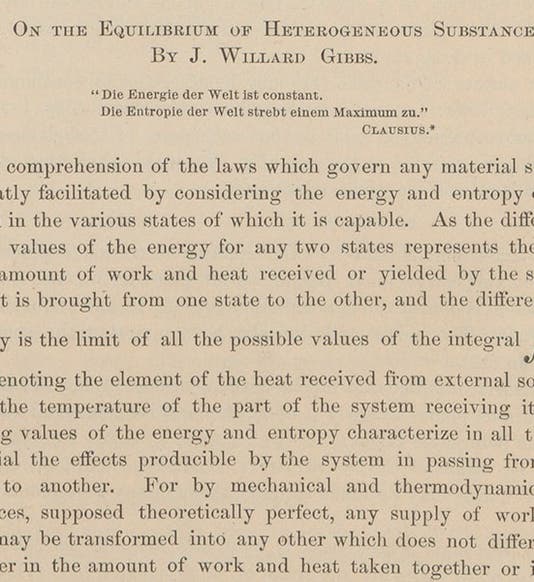

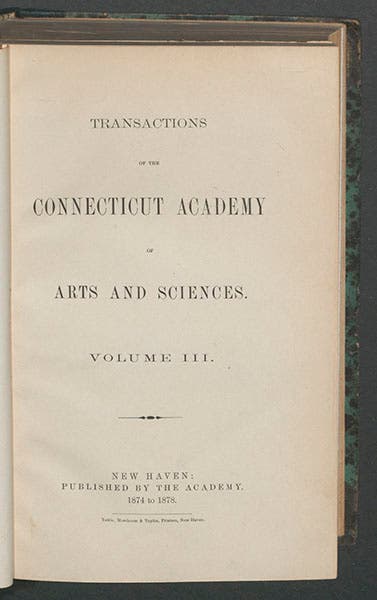

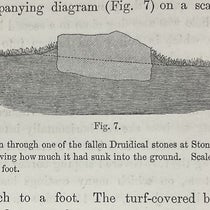

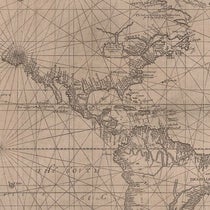

In 1876 and 1878, Gibbs published two papers that provided the first firm mathematical foundation for chemical thermodynamics (what we would now call physical chemistry); we reproduce the first page of the first paper here (first image). The papers were collectively called “On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances,” not exactly a catchy title, and both were published in the Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, a new journal that was considerably more obscure that the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (fourth image). Fortunately, Gibbs sent offprints to everyone he considered important in the field, so that Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann, for example, came to understand that a rare mathematical talent was working in the boondocks of New Haven, Connecticut. There were very few in this country, however, who were aware of Gibbs’ accomplishments, or could have understood and appreciated them, had they known.

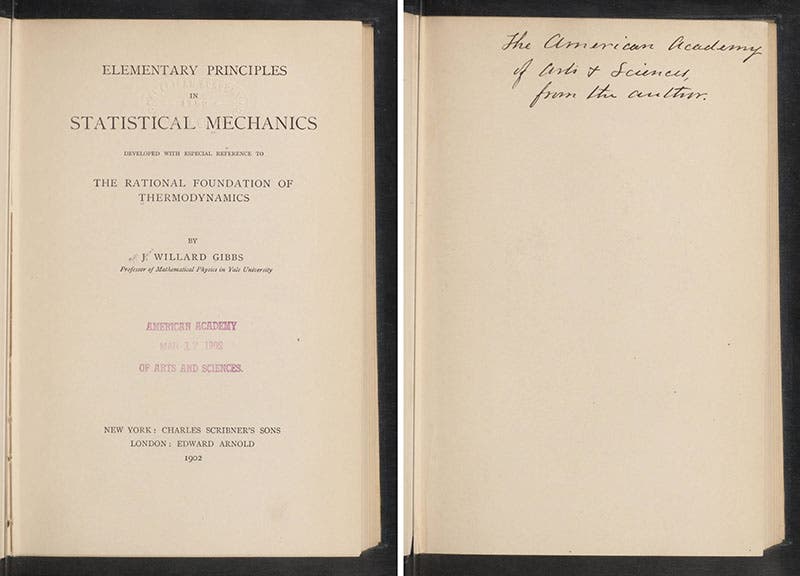

Some 25 years later, Gibbs published another bombshell, this time a book. Again, the title won’t wow you: Elementary Principles of Statistical Mechanics (1902). But it is exactly the right title, since Gibbs did indeed lay out the fundamental principles of statistical mechanics. Along with (and independently of) the Austrian Boltzmann, Gibbs showed that one can use statistics to calculate with great exactness the state of systems containing large numbers of particles (atoms and molecules), even if one doesn’t know the precise nature of those particles.

We have in the Library Gibbs’ early papers on thermodynamics – the volume of the Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Sciences that contains them rests in the History of Science Collection vault, not too far from his 1902 monograph on statistical mechanics. Our copy of the 1902 book was originally presented by Gibbs to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston; the title page carries the Academy's date stamp (Mar. 17, 1902), and the first free end-paper has the inscription "from the author," probably not in Gibbs’ hand, but possibly so (fifth and sixth images). When the Academy collection came to our Library in 1946, this book, along with the Connecticut Academy Transactions, took up residence in Kansas City.

Before the Nobel Prizes were established, the highest award a scientist could hope to attain was the Copley Medal of the Royal Society, and Gibbs received this honor in 1901. The first Nobel Prizes were given that same year, and had Gibbs lived just a little longer (he died in 1903), he would almost certainly have received one, although there would have been some debate as to whether it should be in Chemistry or Physics.

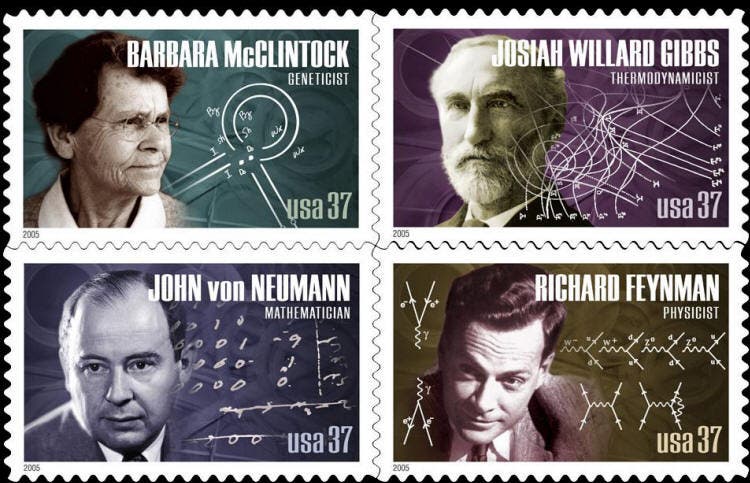

When the U. S. Postal Service issued its first series of American Scientists postage stamps in 2005, Gibbs was one of the first four chosen to be honored. He is in the upper right of the block of four (seventh image).

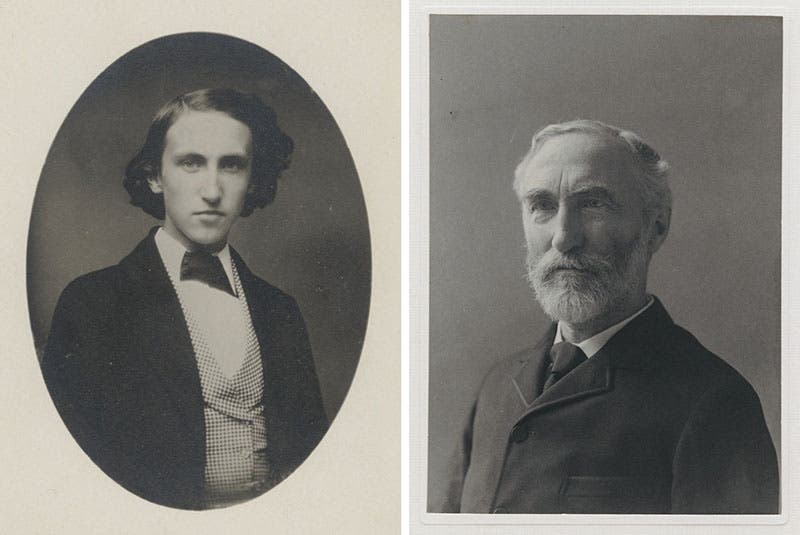

Gibbs was buried in Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut, right next to his beloved Yale University, where his memorial slab still lies (eighth image). The two charming portraits (second and third images) are in Yale’s Beinecke Library.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.