Scientist of the Day - Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood, an English potter, was born July 12, 1730. Wedgwood was an inaugural figure in the Industrial Revolution that radiated out from the Midlands of England in the 1760s. He developed the famous Wedgwood line of pottery and built a factory called Etruria in Staffordshire to produce this pottery. The factory lay right along the Trent and Mersey canal that Wedgwood helped sponsor, so he was able to easily import clay from Cornwall, and distribute his wares to all of Great Britain and beyond. We see below a sample of his “creamware,” in this case a “frog service” platter made for Catherine II of Russia.

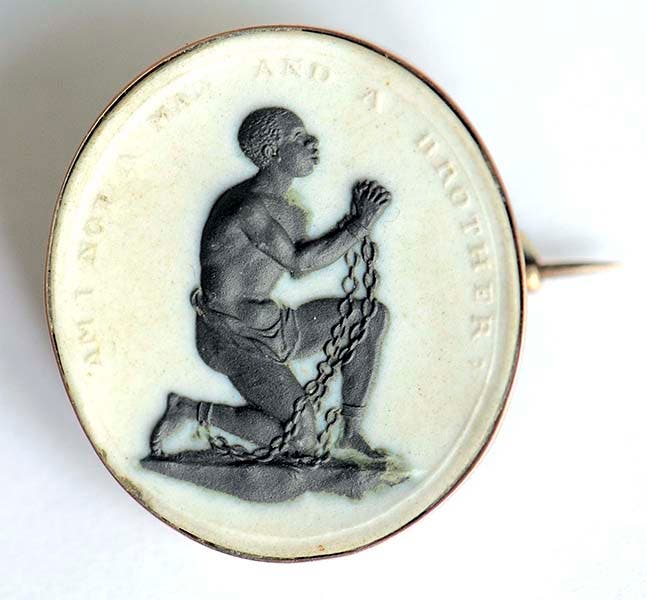

Wedgwood was a vocal opponent of slavery, and he devised a ceramic medallion for the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade that was widely distributed, depicting a slave in chains, with the motto, "Am I not a man and a brother?" (third image, below). Wedgwood was also a member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, a group that included the manufacturer Matthew Boulton and his associate James Watt, the geologist John Whitehurst, the painter Joseph Wright, and the physician Erasmus Darwin. Josiah became great friends with Erasmus, and a marriage was arranged between Josiah's daughter Susannah and Erasmus's son Robert. The most notable fruit of this union was the naturalist, Charles Darwin. Charles would later marry a Wedgwood himself, and since his new father-in-law was also named Josiah, we tend to use the name Josiah I for the founder of the pottery chain, and Josiah II for the son and father-in-law of Charles Darwin.

Josiah I made a significant contribution to science with his development of a temperature scale to measure very hot temperatures, and with the invention of a thermometer to measure those temperatures. The temperature of a pottery kiln can be 1300 degrees Fahrenheit, but since the mercury of a conventional thermometer boils at about 670°F, there was no way to measure that temperature. Knowing the temperature is important because the successful firing of porcelain is very much temperature-dependent. Wedgwood discovered that small blocks of clay would shrink in a kiln, and the amount of shrinkage was related to the temperature – the higher the temperature, the more the blocks shrank. So Wedgwood invented the clay pyrometer (the term pyrometer is used for thermometers that measure high temperatures). You put a couple of plugs in the furnace, wait a few minutes, retrieve and cool them, and then slide them into a slightly converging slot that measures their width precisely, with a scale on which the temperature can be read directly – in degrees Wedgwood! He announced his pyrometer and temperature scale in a paper read to the Royal Society of London in 1782 and published the next year in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions. The Society promptly made Wedgwood a fellow, legitimizing his new status as a man of science. We have the paper in our serials collection, and I read it, but there are no images and nothing to display here except the first page, so I did not have it scanned for this occasion.

The pyrometer was very useful, but naturally Wedgwood and all other students of thermometry wanted to know what the temperature was in degrees Fahrenheit. In a subsequent paper (1784), Wedgwood attempted to correlate the two scales, using the expansion of silver as an intermediary scale to link the two. He ended up concluding that the Wedgwood degree was equivalent to 130 Fahrenheit degrees, with a zero point at about 1080°F. Both of these were considerable over-estimates, as was later shown. But it didn’t matter, really, since the clay pyrometer did its job no matter what the real temperature was. Wedgwood gave a clay pyrometer set to any scientist who wanted one, and even offered one to King George III, which is now in the Science Museum, London. We show a set in the Galileo Museum in Florence (fourth image, above).

Staffordshire has produced many great potters and pottery firms, but in Stoke-on-Trent, or The Potteries, as it is often called, Wedgwood is hailed as the father of the entire industry. A handsome bronze statue was erected in 1862, sculpted by Edward Davies, and placed so that it was the first thing you saw when you came out of the train station at Stoke, and it still is (fifth image, above). Much later, a second bronze was cast from the original plaster mold, and it is in the courtyard of the present-day Wedgwood showrooms in Barlaston.

The next time we celebrate Wedgwood – this first post was too long in coming – we will talk about his long and ultimately successful attempt to replicate the celebrated Portland Vase in Wedgwood jasperware (he is holding a ceramic Portland Vase in the statue above), and about his decision to have his right leg amputated at mid-thigh when he was but 38 years old, a decision he never regretted.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.