Scientist of the Day - Joseph Priestley

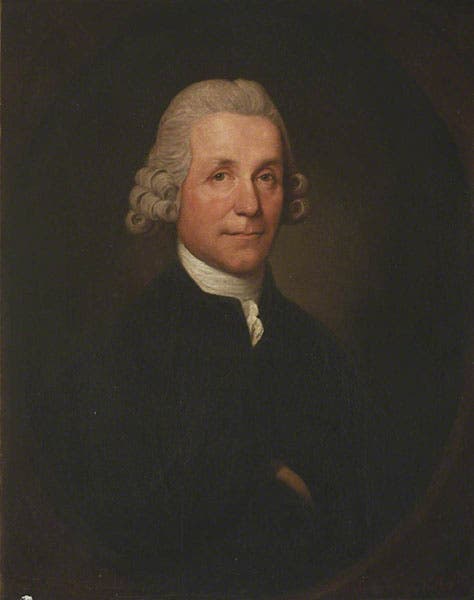

Joseph Priestley, an English (and later American) religious dissenter and natural philosopher, was born Mar. 13, 1733, in West Yorkshire. Born into a dissenting family, Priestley was educated by tutors and in dissenting academies, with a large modicum of self-education mixed in. After a near-fatal illness as a child, he decided that religion should be rational, like philosophy, that salvation should be achievable by anyone, and that education was the key to it all. After several unsuccessful positions in parishes, he set up his own school in Suffolk. He was an innovative teacher, writing his own English grammar, and devising aids like wall-chart timelines to help his students. This school was so successful, that he received an invitation to teach at Warrington Academy, then part of Lancashire (but now in Cheshire), which was a distinguished dissenting academy. It was while at Warrington that Priestley decided to write a history of electrical science, which would be his first scientific treatise.

By the 1760s, electricity was becoming a mature science, after a series of discoveries and inventions that began about 1720 with Francis Hauksbee inventing the first powerful electrostatic generator, followed by important discoveries by Charles du Fay and Stephen Gray in the 1730s of electrical conduction, and the fact that there are two kinds of electricity, and then accelerating rapidly in the 1740s with the discovery of the Leyden jar by Pieter van Musschenbroek, and the invention of prime conductors that could be charged by electrostatic generators. Benjamin Franklin flew his kite in 1752 and published Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1751-54), in which he offered up the first useful theory of a single electrical fluid, explaining in the process how Leyden jars worked.

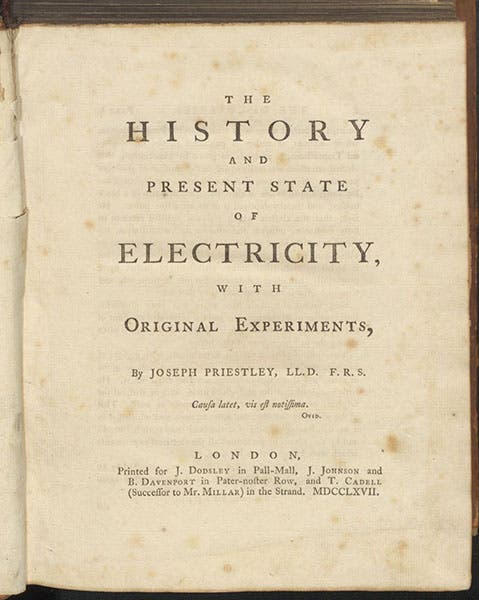

By 1764, when Priestley got interested, the principal electrical experimenters in England were William Watson, John Canton, and, for many months of the year, Benjamin Franklin. Priestley managed to get introduced to all of them and soon was begging them for books – apparently the library at Warrington Academy was not well stocked with treatises on experimental natural philosophy. He managed to secure a Hauksbee-style electrical generator, and a bank of Leyden Jars, and he carefully worked his way through 40 years of electrical experimentation. He decided that since no one had written a history of electrical discoveries (and indeed, no one had), he would do so himself, even though he had made no important discoveries of his own. He compiled his treatise rapidly, for it emerged from the press in 1767 as The History and Present State of Electricity, with Original Experiments. We have two copies of this thick quarto in our collection, one from the Honeyman Collection, which we bought at auction in 1980, and the other from the Library of the Engineering Societies of New York, which we acquired in 1995. Our images for this post come from copy 1, the Honeyman copy.

Priestley divided the history of electricity into ten periods. The first was everything before Francis Hauksbee, which means William Gilbert and Otto von Guericke (period 1); then Hauksbee (period 2); Grey and du Fay (periods 3-5); John Desaguliers (period 6); the experiments of “the Germans” (period 7); the discovery of the Leyden jar (period 8); Franklin’s discoveries (period 9); and the present day since Franklin (period 10). Covering all 10 periods took him about 430 pages. Then, in the second part (300 more pages), Priestley discussed theories of electricity, of which there were many, but none that were superior, in his opinion, to that of Franklin. He also offered up a variety of original discoveries of his own, mostly minor ones.

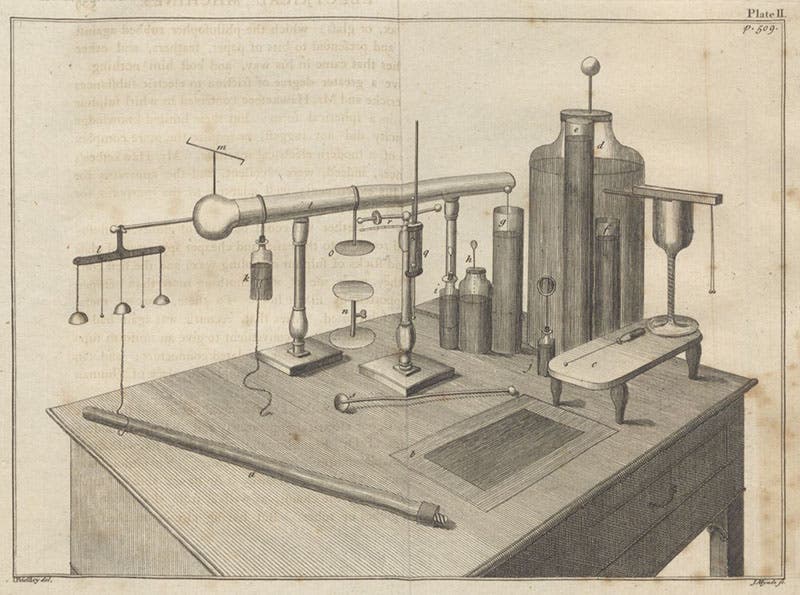

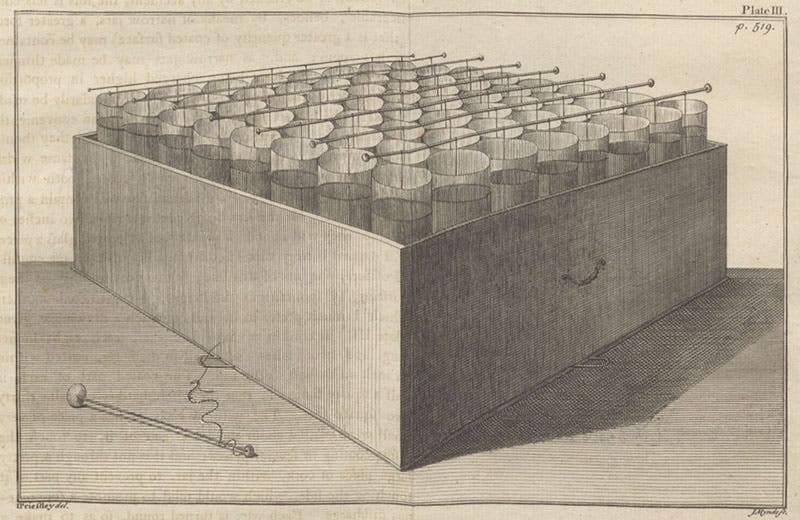

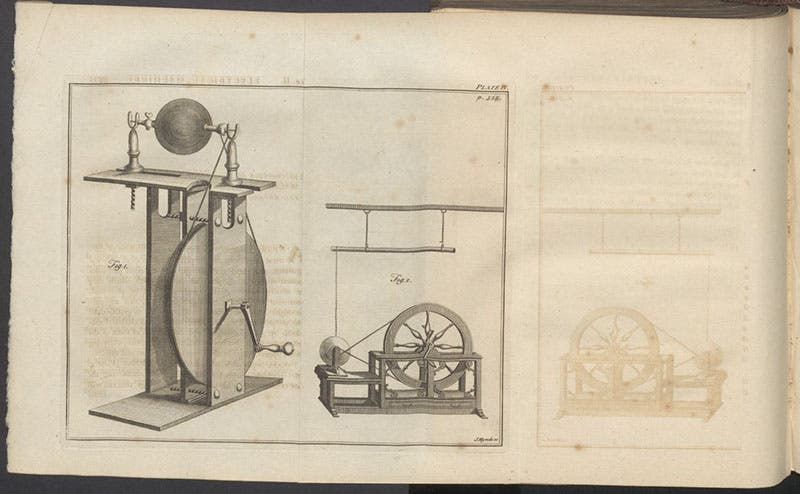

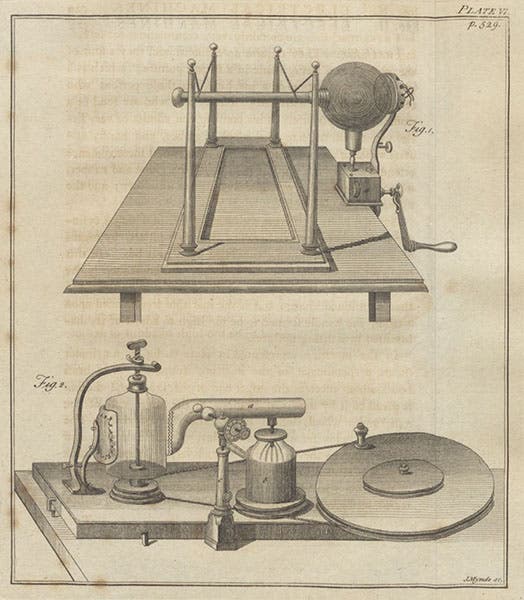

Priestley accompanied his text with 7 folding engravings, which he drew himself, and which were engraved by the Royal Society engraver, James Mynde (Priestley had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1766, thanks to the efforts of Watson, Canton, and Franklin, and perhaps this gave him access to their engraver). We include four of those plates here, showing: a table full of Leyden jars, with a prime conductor (first image); a bank of Leyden jars, linked together in parallel to produce quite a discharge (fourth image); a Hauksbee-style electrical generator (fifth image), and two electrical machines of his own devising (sixth image).

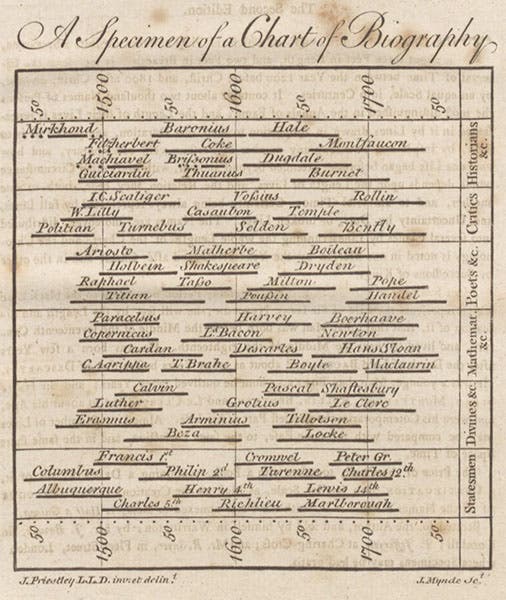

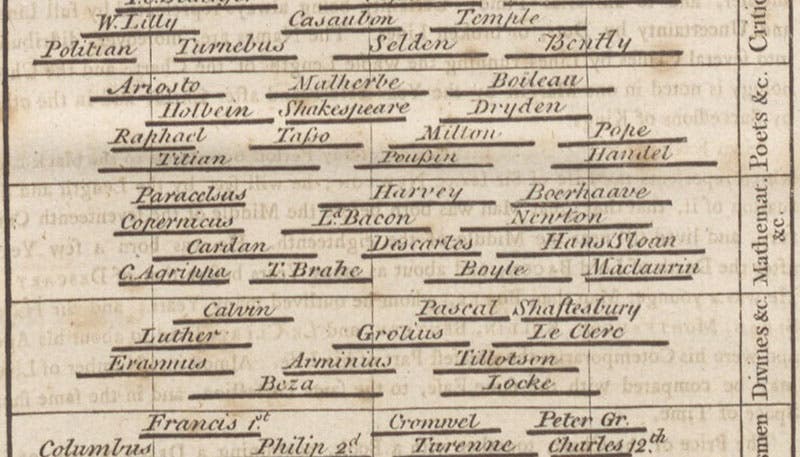

At the very end of the book, after even the Index, Priestley appended a small “Specimen of a Chart of Biography.” The chart from which it was taken was a wall chart that Priestley used in his classes at Warrington, which were later widely distributed throughout England. Since it is unusual, and unexpected, we reproduce here the entire specimen (seventh image) and a detail, where you can read the names (and see the life-lines) of Newton, Bacon, Copernicus, and others. I was interested to see Hans Sloan promoted to the ranks of the mathematicians.

We acquired our copy of Priestley’s Electricity at the sixth auction of the Robert Honeyman collection, on Nov. 11, 1980. As our last image, I show a detail of the inside front cover (called the front paste-down), where you can see Honeyman’s notes at upper left of his acquisition of the book in 1930 at a Sotheby auction; the bookplate of the original 18th-century owner, Philip Puleston of Eclusham in Wales; Honeyman’s red, gold-tooled, leather bookplate, and the bookplate of our Library. They make an attractive array of acquisition history.

Priestley is better known for his later chemical investigations, which included his independent discovery of oxygen in 1774, and for his move to the United States after his Birmingham home was torched by an anti-dissenting mob in 1791. You may learn about this part of his life at a previous post on Priestley in 2020, and a post before that in 2015.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.