Scientist of the Day - Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, a French inventor, was born Mar. 7, 1765. Niépce (pronounced Nee-EPS) invented an internal combustion engine and a velocipede, but he is best remembered (or not remembered) for the invention of photography. It was about 1822 that Niépce discovered how to make a permanent record of a pattern of light. He first covered a sheet of pewter with a solution containing bitumen (asphalt). When the solvent dried, the plate was covered with a thin layer of bitumen. It the plate were exposed to light (for example, in a camera obscura), those areas of bitumen that received light exposure would harden. If the tin plate were then washed again with solvent, the unexposed bitumen would dissolve and wash away, while the hardened bitumen, now insoluble, would remain. The result was a picture, and it could be viewed directly, or it could be used as a relief plate to print a copy of the image. Niépce called his images heliographs--sun pictures.

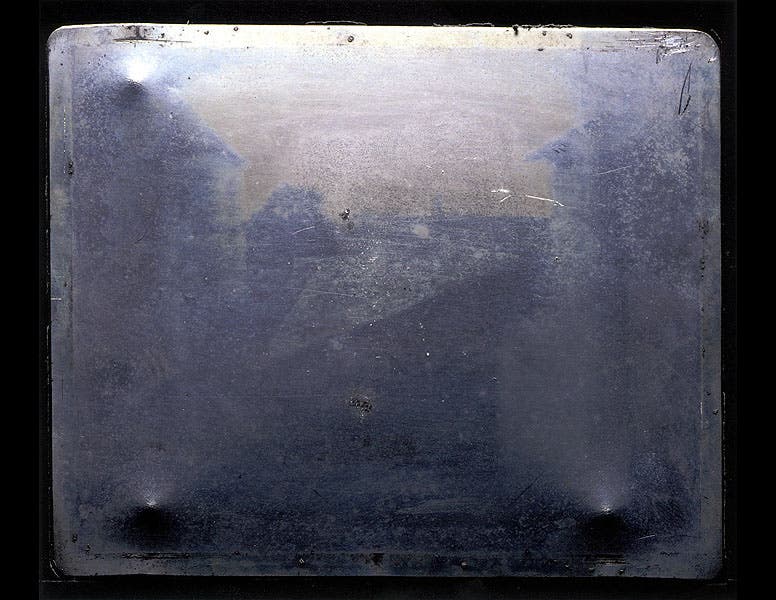

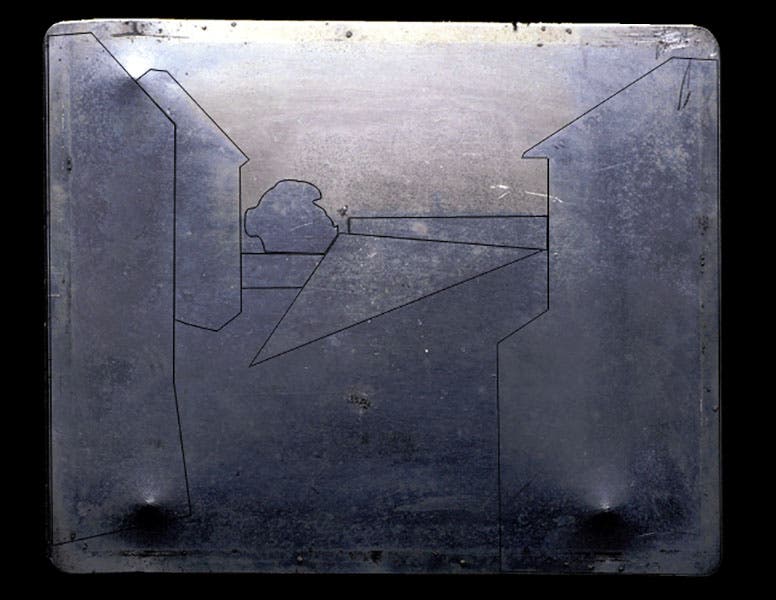

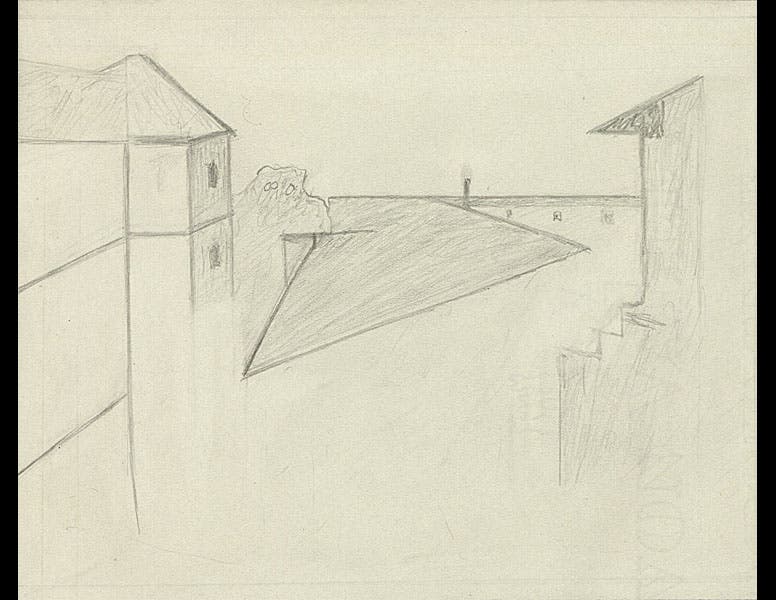

In 1826 or 1827, Niépce made an exposure from his window, known as View from the Window at Le Gras, which took several days. It is the earliest photograph from nature that survives (second image), and you can see it in a special booth in the lobby of the Harry Ransom Center (HRC) at the University of Texas at Austin (first image). It is almost impossible to make out any details in the original; an enhancement helps (third image). In 1952, when the original came into the hands of Helmut Gernsheim, a gelatin silver print that was made directly from the original; it gives you an idea of what the original captures: a view out a window, showing some neighboring buildings, a roofline, and a tree (fourth image). And if you prefer a less subtle approach, the HRC has a drawing that Hernsheim made when he first acquired the photograph (fifth image).

Why then is the invention of photography usually credited do Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot? It is a convoluted and sad story. Niépce travelled to England in 1827 to tend to his mentally ill brother, and he brought several heliographs with him. He met people who were quite interested in his process, and he tried to arrange to give a demonstration to the Royal Society of London. However, everything went wrong, and it really was no one's fault. The Royal Society was practically dysfunctional at the time, as the president, Humphry Davy, was dying, and there was considerable scrambling to determine his successor. John Herschel, who would be a photographic pioneer himself in the 1830s, was so disgusted with the Society that he resigned his position as secretary and refused to attend meetings. The upshot was that the presentation never came to pass, and the people who would have been the most interested in Niépce’s demonstration, like Herschel, never met Niépce or saw his work. Niépce returned home, his heliotypes still in his luggage, and although he lived until 1833, and collaborated at the end with Louis Daguerre, he gradually disappeared from public view. When the Daguerrotype (a different type of photographic process) was first demonstrated to a revitalized Royal Society in 1839, Niépce's name was all but forgotten. Niépce did all the right things, but he never reached the right people. Had he made his trip to England a year earlier, or even a year later, he might have found a receptive audience, and the history of photography might have played out quite differently. Life is like that, sometimes. Fortunately, that one exposed pewter plate is still with us, reminding all who see it that Niépce deserves more than posterity has provided him.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.