Scientist of the Day - Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry, an American physicist, was born Dec. 17, 1797. Henry began teaching science at the Albany Academy in 1826, and moved to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1832. Henry is well known for the work he did in the 1830s on electricity; he discovered electromagnetic induction – that a current is induced in a conductor when it is moved across a magnetic field. This discovery, made independently by Michael Faraday in England (who published first and usually gets more of the credit) made possible the design and construction of electric generators and electric motors. However, it was Henry alone who invented the electromagnetic relay (1835), which effectively allowed one to amplify an electric current, thus making the telegraph of Samuel F.B. Morse a possibility instead of a dream.

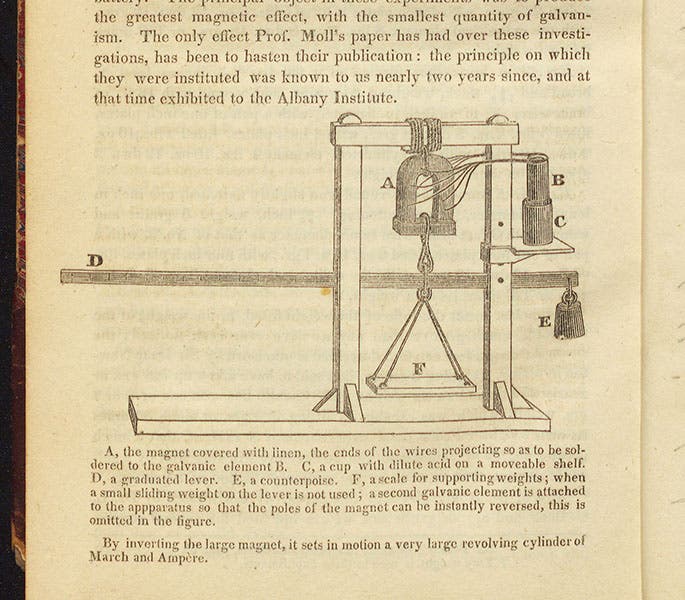

Much of Henry’s early work in electricity appeared in papers published in the American Journal of Science, commonly known as Silliman’s Journal, after the name of its editor, Benjamin Silliman, a professor at Yale College. One of Henry’s first papers discussed a powerful electromagnet that Henry constructed at Albany, and the paper included a wood engraving of his device (second image, just above). The next electromagnet he made was presented to Silliman at Yale, and Henry described it, but did not illustrate it, in the next issue of the journal (third image, just below). So we show a photo of the still-surviving coil (fourth image), by way of introducing you to the Joseph Henry Project at Princeton, which is filled with information and images – everything you could possibly want to know about Henry, and considerably more. Here is a link to the page on the Yale electromagnet.

Henry's greatest legacy may be the Smithsonian Institution. When the Institution was formally founded by Congress in 1846, Henry was appointed the first Secretary (in essence, the Director), and during his tenure of 32 years, ended only by his death in 1878, Henry largely determined the shape and scope of that Institution, as well as the best way for the government to promote science. For a scientific bureaucrat, Henry was amazingly popular. On the day of his funeral, the entire government shut down, and the President, Vice-President, Justices of the Supreme Court, and all the members of Congress attended the service. Henry is now commemorated by a statue near the northwest entrance to the Smithsonian Castle, sculpted in bronze by William Wetmore Story. For the occasion of the unveiling of the statue in 1883, John Philip Sousa was commissioned to write a march, which he did, naming it the Transit of Venus March, after the just-passed astronomical event of 1882. Why it was not called the Joseph Henry March, I cannot say.

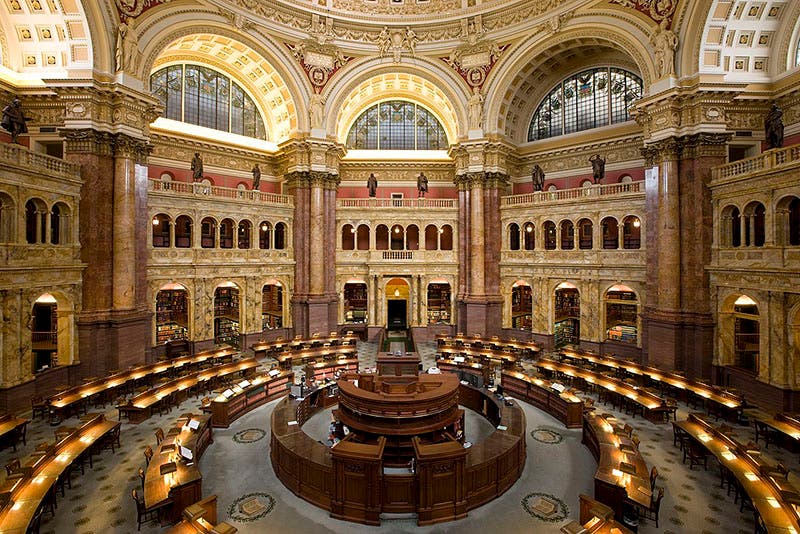

Henry was honored once more when the first Library of Congress building was opened in 1897 (it is now called the Thomas Jefferson Building). Sixteen bronze portrait statues were placed around the main Reading Room, under the dome; in a wide view, you can see 8 of the statues (but not Henry’s) (sixth image, just below). Eight disciplines were represented by two statues each; so, for example, there are two artists (Michelangelo and Beethoven), two poets (Homer and Shakespeare), two religious figures (Moses and Paul), and two scientists. The two scientists chosen were Isaac Newton and Joseph Henry. Henry’s statue is our opening image.

Henry was buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C., where there is a typically modest memorial stone.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.