Scientist of the Day - Joseph Christmas Ives

Ordinarily, if you were a scientist born on Christmas, you could never be a Scientist of the Day, because the Library does not normally add new posts on holidays. But if you were born on Christmas, and were also named after Christmas, and did something notable, surely someone would make an exception for you. Today we are making that exception, to accommodate Joseph Christmas Ives, born Dec. 25, 1829, in New York City. Ives graduated from West Point, joined the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1854, and promptly took part in several surveying expeditions into the American West. In 1857, now a first lieutenant in the Corps, Ives was commissioned to mount an expedition to explore up the Colorado River, from the Gulf of Mexico to the limit of navigability. To fulfill this charge, Ives had a paddlewheel steamboat constructed in Philadelphia, dismantled, and shipped to the west coast.

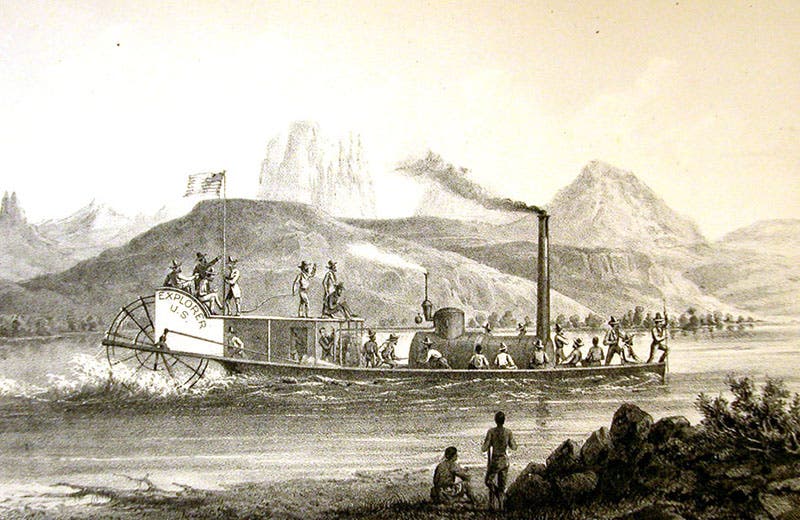

Cognizant as we are of the time it takes to get anything done in the enlightened 21st century, it is of note that Ives received his assignment in early June of 1857, and he had a shipyard building his boat within the month. The craft, named the U.S. Explorer, was finished and ready for shipment by mid-August, was loaded onto an Atlantic steamship and taken to Panama, where it was disembarked and ferried across the Isthmus by the Panama Railroad, and then taken by a second ship to San Francisco, where it arrived on Oct. 1. By Nov. 1, the party had been assembled and Ives was on his way to the Gulf of California, with his ship, still in pieces, on the deck of his transport. It took nearly a month to reach the mouth of the Colorado, where they arrived on Nov. 29. By Dec. 21, the Explorer had been re-assembled and tested, the boiler was fired up, and the expedition was underway, a little over six months since the Secretary of War had first envisioned the project (second image).

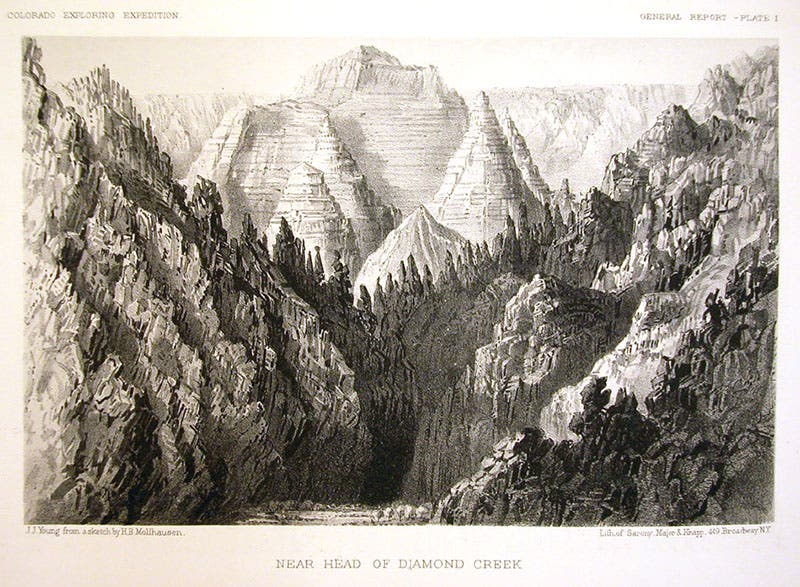

The Explorer would steam its way up the Colorado River all the way to the Black Canyon before it ran out of steerage way. The men then proceeded on foot and reached the Grand Canyon proper before turning back. When Ives returned in 1858, he promptly wrote a narrative of the expedition, which was delayed in publication and did not appear until 1861, as Report upon the Colorado River of the West, Explored in 1857 and 1858. The Report benefitted greatly from the presence on the expedition of J.J. Young, an American artist; Balduin Möllhausen, a German artist, and Frederick W. von Egloffstein, a German-born cartographer. Young and Möllhausen made drawings, Egloffstein made maps, and the Report is illustrated with both.

We show here several examples of the work of Young and Möllhausen. Most of our images here are details, but the fourth image, showing Diamond Creek in Arizona, is a full plate, with the attribution to Young and Möllhausen visible at the bottom. The fifth image is a detail showing some of the Moquis (Hopi) pueblos they passed in Arizona, and the sixth shows part of the Grand Canyon that they explored on foot.

We do not show any of the maps of Egloffstein, because we do not have any of them scanned, and we cannot make new scans right now. But his maps are quite remarkable, utilizing a half-tone technique that he developed, even before half-tone was supposedly invented. Perhaps we will have a chance to obtain some scans before Egloffstein’s birthday next May, and if so, he will have his own chance to be a Scientist of the Day.

For those of you who write trivia contest questions, and I know at least one of you who does, try this one at your next event: What was the first ship to cross the Isthmus of Panama? If a contestant is well informed, he or she might say, the SS Ancon, on Aug. 15, 1914, the day the canal opened. A wiser player might respond, no, it was the Alexandre La Valley, a crane boat, which navigated the entire canal six months earlier, in January of 1914. But the winner will reply, the Ives steamship Explorer, in September of 1857. Granted, it was in pieces, and riding on a series of railroad flatcars, but the complete steamboat was there, and it did traverse the entire Isthmus, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. So far as I know, the first to point this out was our own former Rare Book Librarian, Bruce Bradley, in the section that he curated of the Library’s 2014 exhibition, The Land Divided, The World United: Building the Panama Canal. You can read his account here, if you scroll down about three screens.

Finally, I put the lithograph of the Colorado Plateau encampment first in this post, because it looks rather festive, in a holiday kind of way. It gives me the chance to wish all of you either merry Christmas or happy holidays, with the hopes that the New Year will bring a much brighter 2021.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.