Scientist of the Day - Joseph Bramah

Joseph Bramah, an English mechanic and inventor, was born Apr. 13, 1748. Bramah invented many things – an improved water closet, a banknote numbering press, and a hydraulic press. But he is best known for his unpickable lock. He went into the lock business in 1784, with a new kind of lock that was very secure. In 1789 he hired an 18-year-old budding mechanical engineer named Henry Maudslay, who would go on the become one of the great precision engineers of the early 19th century. But in 1789, he had only potential, which Bramah was astute enough to recognize. He gave Maudslay the challenge of helping him design and build a lock that could not be picked. By 1790, they had their baby. The lock looked like a modern padlock, although bigger and heaver (first image). The key was not notched on the side like modern padlock keys, but instead had 18 slots of varying depths cut into the end. When the key was inserted, the notches pushed 18 "sliders" down to different depths, which then allowed the key to rotate and release the hasp. Most Bramah locks of this type had 4-6 sliders, with 4-6 slots cut into the keys; we show a photo of three of these simpler keys as our third image, below. Eighteen 18 notches for 18 sliders was quite a bit more complicated, and much harder to pick.

Bramah displayed the new lock in the front window of his shop with a black wooden placard sporting the following challenge in gold ink: "The Artist who can make an Instrument that will pick or Open this Lock shall Receive 200 Guineas the Moment it is produced." The lock came to be known as the Challenge Lock and it stood in the window, unpicked, through Bramah's death in 1814. The lock still survives, and until recently was on display in a reproduction of the store window in the Science Museum, London (fourth image, below). I understand that the lock has now been removed to a separate location.

Bramah's sons took over the business, and the lock stayed where it was in the window until August of 1851, when it was successfully opened by an American locksmith, Alfred Charles Hobbs, who was representing his American employer, Day & Newell, at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. However, it took Hobbs 51 hours of picking, spread over 16 days, and a whole host of very specialized tools, to open the lock. We told the story in our post on Hobbs, where you may also see a view of the Challenge Lock key, removed from the lock. If anything, the reputation of Bramah & Sons was only strengthened by the difficulty Hobbes had in picking the Challenge Lock.

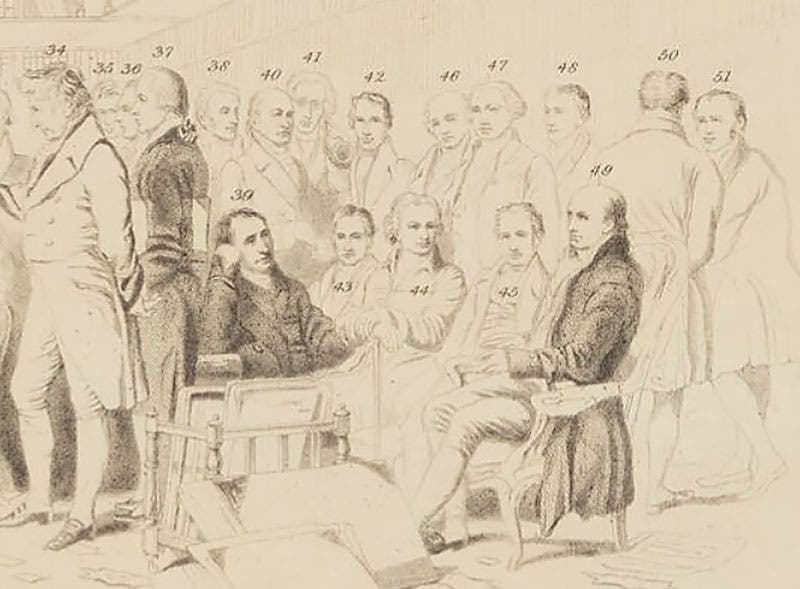

The portrait of Bramah we show here is in the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (second image). Most other portraits that you see online seem to have been derived from this one. The portrait seems not to have been known to John Gilbert (or perhaps did not yet exist) when he sketched out his drawing, “Distinguished Men of Science Living in 1807-08,” in 1862. We have shown the drawing or the engraving that came from it, many times in these posts, most recently when we featured Davies Gilbert and, before that, Edward Charles Howard. We know that John Gilbert wanted to include Bramah in his panorama, because he did include him, but since he had no idea what he looked like, he depicted him with his back turned, at the far right, no. 50, talking to Richard Trevithick, no. 51 (fifth image, below). Our detail is from the numbered key to the engraving, made by William Walker and held by the National Portrait Gallery in London. You can see the complete pencil drawing, the complete engraving, and the complete numbered key at the links. Bramah is the second from the right in all of them. In the complete numbered key, you can see a list of the sitters below, with no. 50 identified as “Joseph Bramah of whom there is no portrait extant”.

Bramah was buried in St. Mary’s Paddington Green Churchyard, in Paddington, Westminster. There is no photo of his memorial on findagrave.com, or anywhere else that I could find. He does have a blue plaque in his hometown of Barnsley, in Yorkshire.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.