Scientist of the Day - Joris Hoefnagel

Joris Hoefnagel, a Flemish painter, miniaturist, and topographical artist, was born in Antwerp in 1542 and died on July 24, 1600, in Vienna (or so it is thought). Joris's father was a merchant, and Joris was intended for that profession, but somewhere along the line he learned to paint. He may have been self-trained, or he may have studied with the painter Hans Bol, a miniaturist himself. In 1576, Antwerp was sacked by Spanish soldiers, the family fortune was plundered, and Hoefnagel became an ex-patriate. He had already traveled to and studied in France, Spain, and England; now he headed to Italy with Abraham Ortelius, the cartographer. His artistic talents were apparently well evident, for he was invited to stay in Italy as a court painter, but instead he chose to accept an invitation to paint at the court of Duke Albert V in Bavaria. Munich cleansed itself of Protestants in 1591, so Hoefnagel moved to the imperial court of Rudolf II, residing first at Frankfurt, and then later at Vienna and Prague. He never did return to Antwerp, although he formed a friendship with fellow exile Carolus Clusius, who perhaps taught him how to paint flowers and fruits.

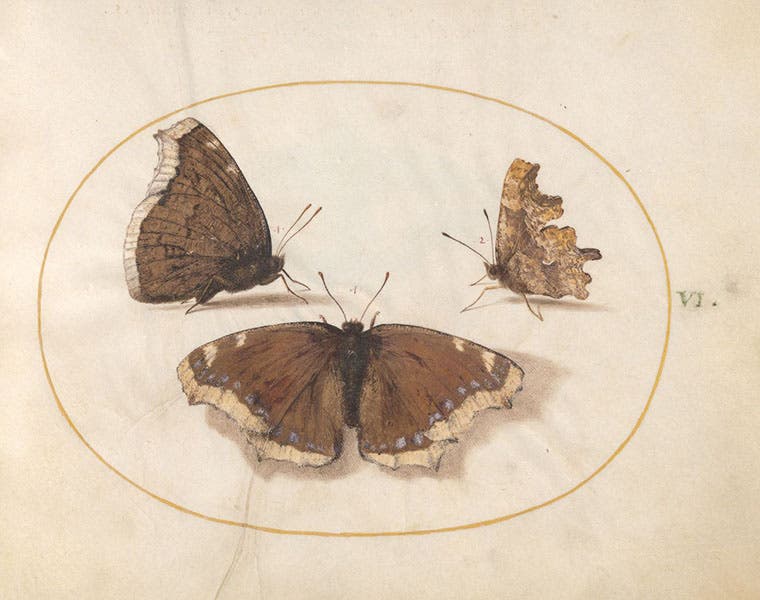

Hoefnagel painted full-size paintings, and large landscape views for cartographical projects, but he seems to have preferred naturalistic miniature painting, and emblems, and their combination, over other forms of artistic expression. We are going to concentrate today on two collections of miniatures. The first is a set of four volumes that now resides in the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, D.C., which is usually called the Four Elements, because its four volumes are titled: Terra, Aqua, Ignis, and Aeir. Each volume contains small (7 x 5 1/2") watercolor and gouache paintings on vellum of living things appropriate for that element, so that mammals and reptiles are in Terra, fish and water animals in Aqua, birds in Aier, and insects in the volume for the element nobody wants, Ignis. Each painting is a group of animals, artfully arranged and delicately colored. Proverbs, adages, and emblematic mottos are written in by hand, in red and black, above and below the painted scene.

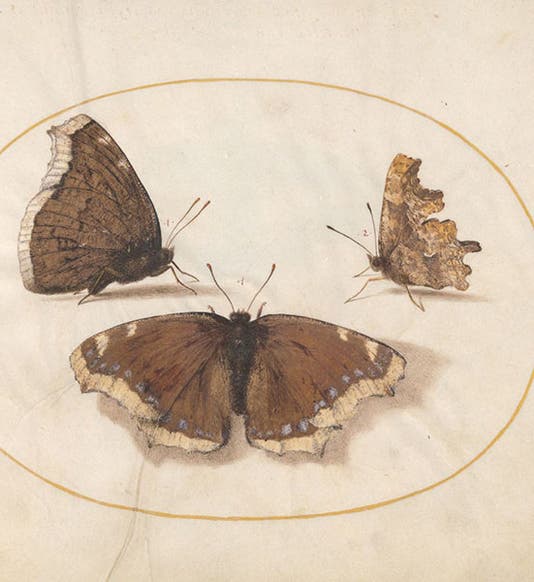

All of the 276 paintings are available on the NGA website (here is a link to vol. 1, Ignis), and all are wonderful, so it was difficult to choose four for reproduction here. I tried to pick some that are not often reproduced. I lead with the mourning cloak butterfly (known in England since Moses Harris in 1766 as the Camberwell beauty), because it just cries out for a close-up detail, which we provide (fifth image), and which reveals the incredible artistry of Hoefnagel’s brush.

The two otters and the otter-like beaver are just charming, and so is the armada of nine sharks, both in the Aqua volume (third and fourth images). I do not have room to include any of the pages that show the smaller insects, such as flies and beetles, but it is evident that Hoefnagel has some sort of magnifying aid to see the detail that he drew. It also seems likely that Hoefnagel’s arrangements of bugs, flowers, fruits, and small animals might have had a strong influence on Dutch still-life painting of the 17th century.

The stag beetle, in the Ignis volume, is regularly reproduced in discussions of Hoefnagel, but we include it here (sixth image) to make the point that Hoefnagel copied many of his figures from the works of other naturalistically-included artists, such as, in this case, Albrecht Dürer. I just discovered that our post on Dürer’s animal and plant drawings discusses only his rhinoceros, so we need to return to him soon, so you can see the original of the stag beetle.

The Four Elements is an artistic wonder, but you need not go seek it out, because by stipulation of the donor, Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald, no one may touch it except a curator, and then only using a delicate metal wand to turn the pages. But you have another recourse if you wish. There is a wonderful book about Joris Hoefnagel, his life, and the composition and evolution of the Four Elements volumes at the National Gallery of Art, published not so long ago by Marisa Anne Bass and called Insect Artifice: Nature and Art in the Dutch Revolt (Princeton University Press, 2019). Dr. Bass connects Hoefnagel’s miniatures to the tumultuous times of the Netherlands under Spanish occupation, providing a social history of the Four Elements, which is invigorating. But the book also includes a centerfold of plates, reproducing 39 of the NGA miniatures at natural size, and including the facing pages with their inscriptions and proverbs, which are almost never shown, even on the NGA website.

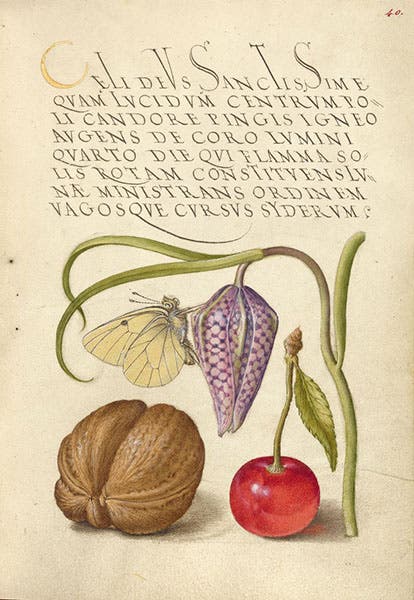

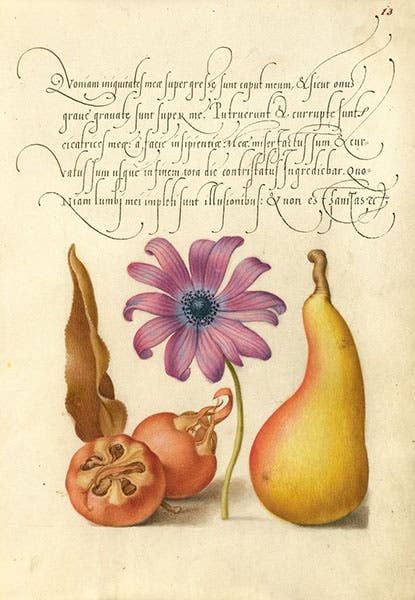

Hoefnagel did lots of other paintings, and we have included here, as our last two images, two Hoefnagel illuminations from another volume, this one on the other side of the country, in the J. Paul Getty Museum. The Mira calligraphiae monumenta was originally a display of calligraphy, created by Georg Bockskay around 1562, and the calligraphy is amazing. But in the early 1590s, long after Bocksay had died, Emperor Rudolf II asked Joris to illuminate it, and that Joris did, with a passion, as if to show that images are better than text any day. These illuminations are charming because they combine zoological and botanical subjects, usually cleverly, and with some stunning color combinations, as in our last image, showing a medlar, poppy anemone, and a pear.

The Mira illuminations were published by the Getty Museum in 1992, edited by Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg, but we do not have that book in our library, nor do I own it. I do however own a small companion publication, Nature Illuminated, by the same authors, which was I suspect a promo for the complete reproduction, but it does include several dozen full-color reproductions of Hoefnagel’s work in the Mira. You can also find all of Hoefnagel’s Mira illuminations online on the Getty Museum website. But like all illuminations, they look better on a printed page.

We do not have anything by Joris Hoefnagel in our library. But Joris had a son, Jacob, with whom he collaborated, and who later published a set of insect engravings based on their work together, which we do have in our collections. So this post can serve to announce a feature post, on Jacob, which we will present in the near future.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.