Scientist of the Day - John Willis Griffiths

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

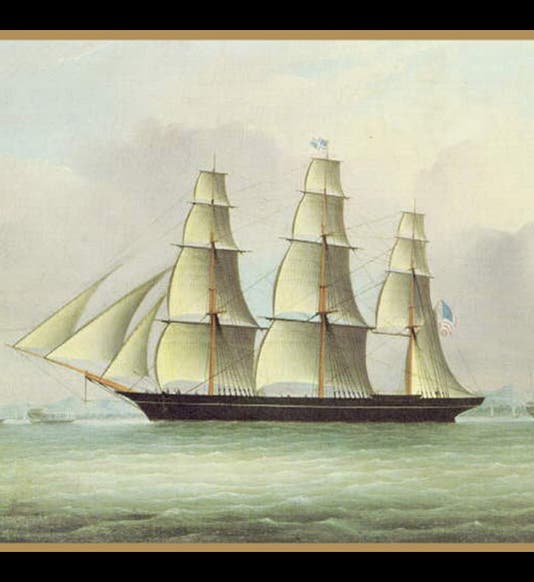

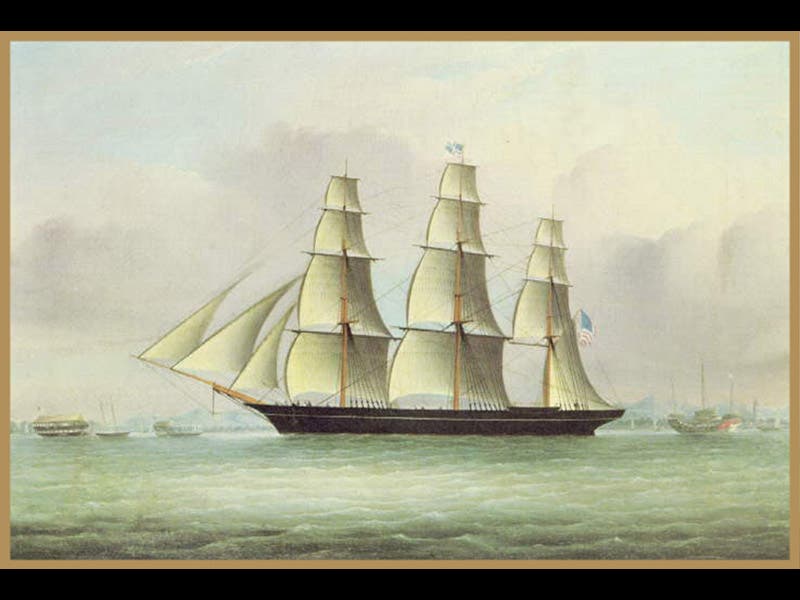

John Willis Griffiths, an American ship designer and naval architect, was born Oct. 6, 1809. In 1841, Griffiths began designing a new kind of sailing ship, the extreme clipper ship . Fast-sailing clipper ships had been constructed in England for about ten years, for the purpose of trading with China and Australia. These two countries were so far away that speed was more important than tonnage, and clipper ships could get to Australia and China and back in about a year, and they were especially suitable for carrying tea, which is not particularly heavy. From the United States, it made more sense to sail around Cape Horn to get to China, which made it an even longer trip. So Griffiths improved the clipper ship with his extreme version. Griffiths’ design had a pointy keel, curved prow and stern, and a bow that was hollowed along the waterline; not much cargo room, but tall masts and thousands of square feet of sails. Most ship builders thought such a ship could not possibly be seaworthy, but one merchant was willing to put up the money, and the shipbuilding firm of Smith & Dimon of New York was happy to build it. The result was the Rainbow, launched in 1845, with a displacement of 750 tons, that was as fast as, well, the wind. After displaying her speed, the Rainbow was put on the New York City-to-Canton run, and it made the first trip in 105 days, about 20 days faster than any previous clipper ship. The trip home was even faster. Another Griffiths’ ship was built in 1846, the Sea Witch, of which we have a painting (first image). In 1848, Sea Witch sailed from Canton to New York in 77 days, a record never beaten by any ship, ever.

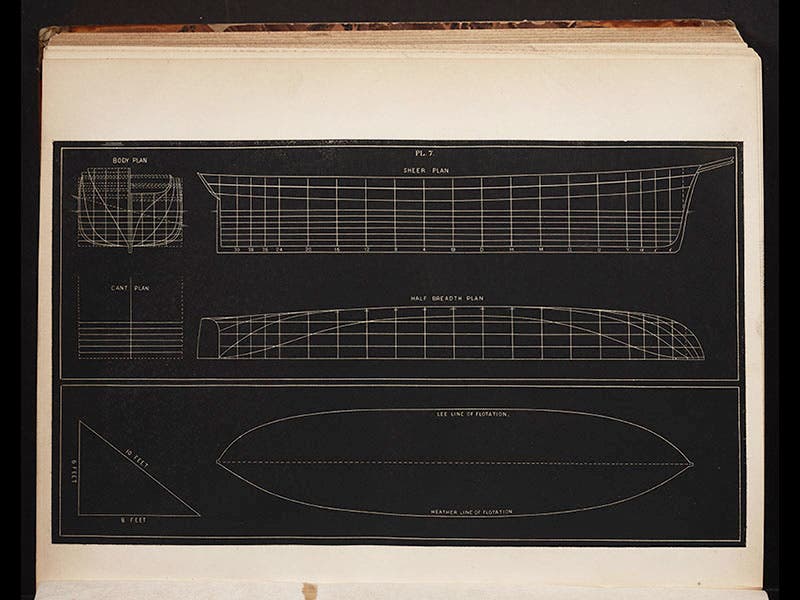

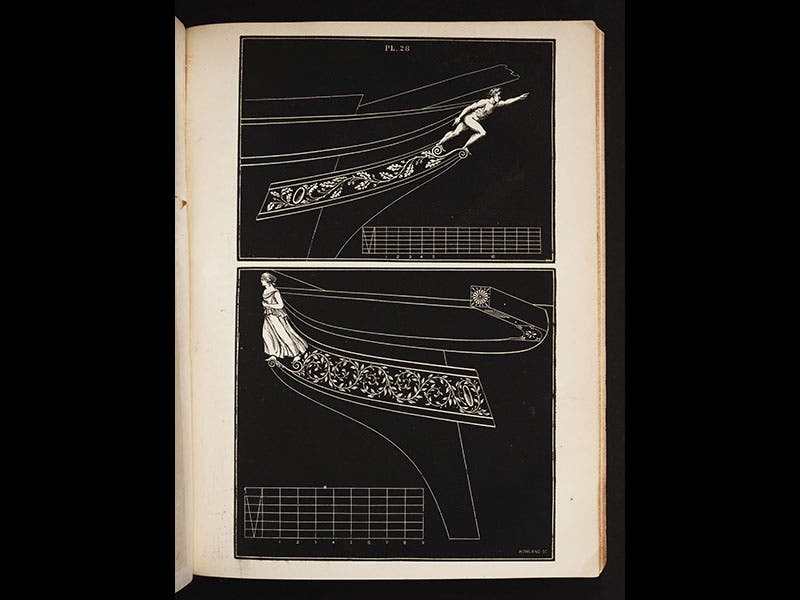

Griffiths’ ships were suddenly in high demand, and he responded not only with more designs, but with a book, Treatise on Marine and Naval Architecture, or, Theory and Practice blended in Ship Building. It has been called the first great American book on marine architecture, and we have a copy in our History of Science Collection. Our copy is dated 1850 and appears to be a first edition, but there may be copies with a date of 1849. The book has 45 plates, mostly line diagrams of hull sections, curious because they are printed like blueprints, white on black. None of them are especially striking unless, perhaps, you are a naval architect. We see two of them, and the title page, above.

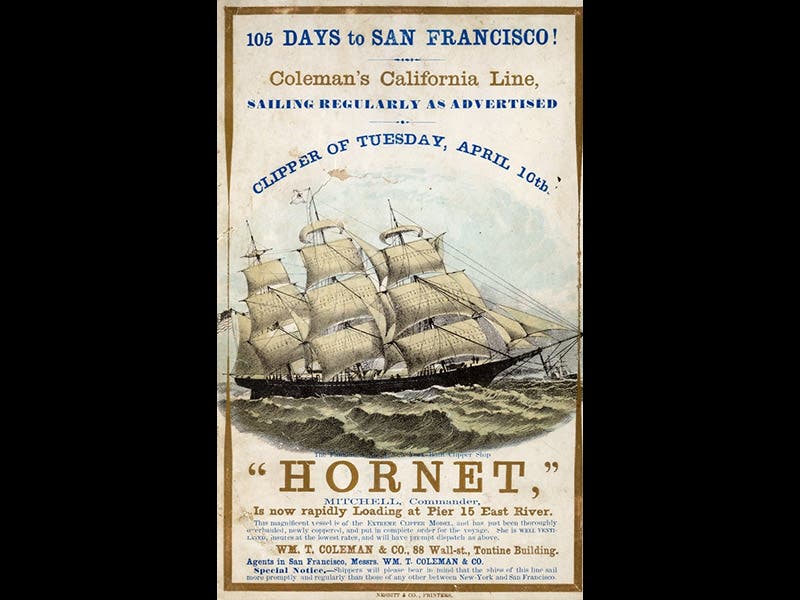

The age of the extreme clipper was a brief one. They grew in popularity when gold was discovered in California in 1848, since the clippers could get from New York to San Francisco faster than anything overland; we see above an extreme clipper of 1851, the Hornet, built for the San Francisco run (fifth image). But the opening of the Panama Railroad in 1855 put a damper on ship travel, and the simultaneous completion of the Suez Canal and the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 made the clipper ship nearly instantly obsolete. None of the early clipper ships survive; the only physical remnant we have of that great age is the Cutty Sark, built 24 years after the Rainbow, and on view today at a mooring in Greenwich, England.

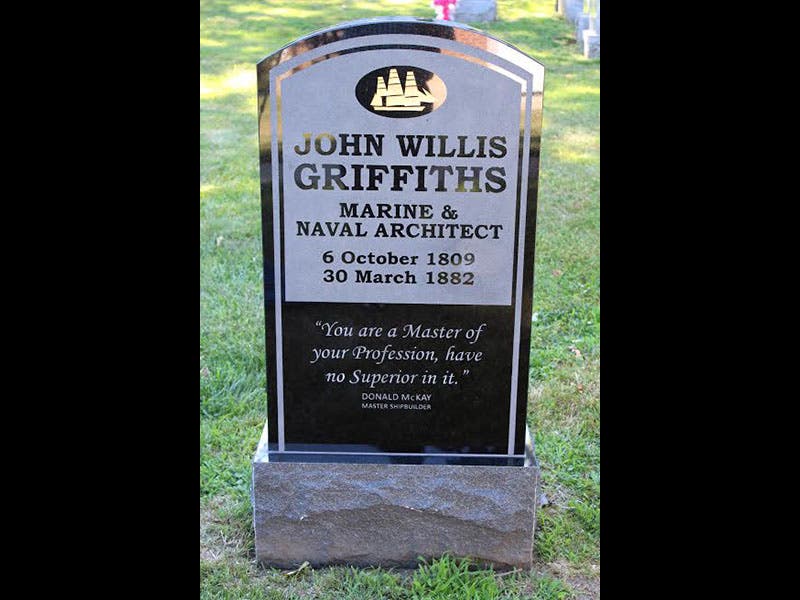

Griffiths died in 1882, having lived a life that was exactly coincident, in years, with that of Charles Darwin. He was buried in a cemetery in Ridgewood, Queens County, New York, and then his grave was neglected and lost over the next century. In 2016, concerned marine historians and ship design buffs, who view Griffiths as a major figure, raised the funds to erect a new memorial in Ridgewood (sixth image). The portrait above (seventh image) is used whenever a picture of Griffiths is needed, but we have yet to determine where it is, and whether it has been authenticated.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.