Scientist of the Day - John William Salter

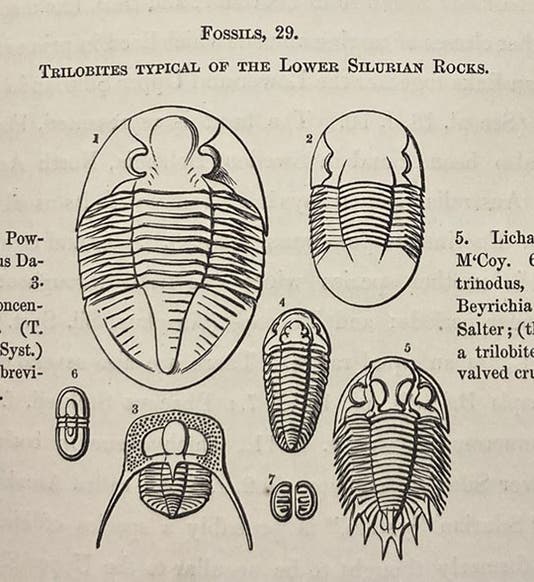

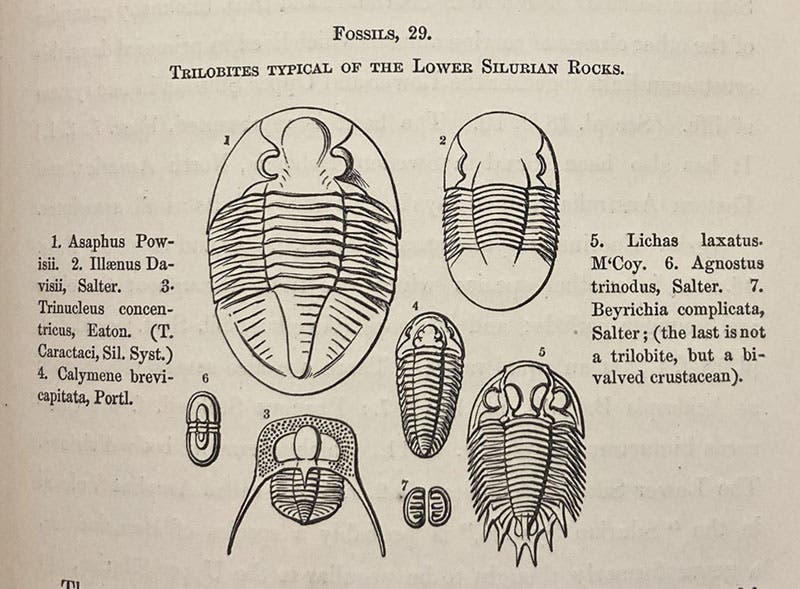

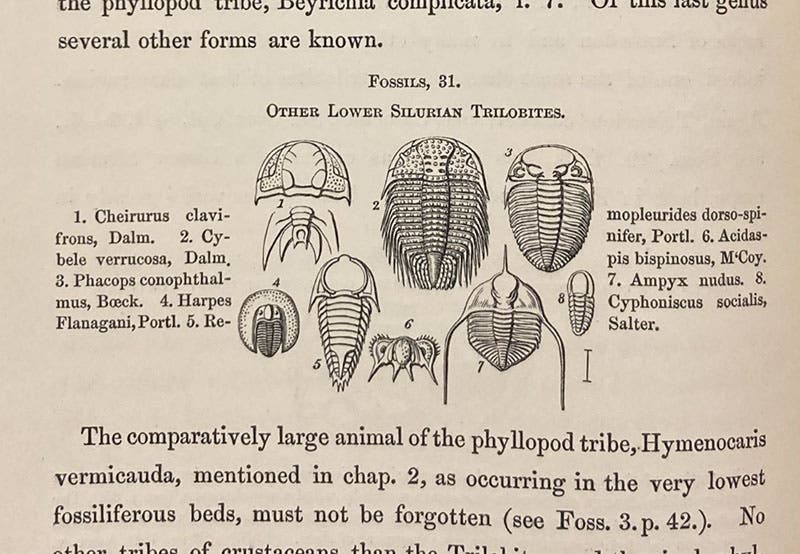

John William Salter, an English paleontologist, was born Dec. 15, 1820, into a lower middle-class family – his father was a bank clerk, just like Bob Cratchit. Young John took the unusual step of apprenticing himself to an artist and engraver, James de Carle Sowerby, in 1835, for a 7-year term. Sowerby came from a family of illustrators and engravers; his father, James, was a respected painter, collector, and engraver, and so was his brother George (who would engrave the plates for Charles Darwin's monograph on barnacles). James de Carle was at the time working on his Conchology, and was also providing the illustrations for Roderick Murchison's Silurian System (1839), and so John Salter got 7 years of exposure to shells, both living and fossil. He preferred the fossil variety. The fossils in Murchison's new Silurian system, exemplars of which came from Wales, were mostly new to paleontology. Salter became an expert on Paleozoic fossils, especially trilobites. He was or became a competent artist and learned the art of woodcutting and engraving from Sowerby as well.

When his indenture was over, Salter went to work for Adam Sedgwick, holder of the Woodwardian professorship at Cambridge and director of the museum there. Sedgwick had also discovered a new geological system in Wales, the Cambrian system, which underlay the Silurian system of Murchison, so he too had many unnamed fossils to describe and illustrate. Sedgwick apparently found Salter to be a valuable, indeed invaluable, assistant, both in the museum, and on the road, as the two made several trips to Wales to gather more fossils.

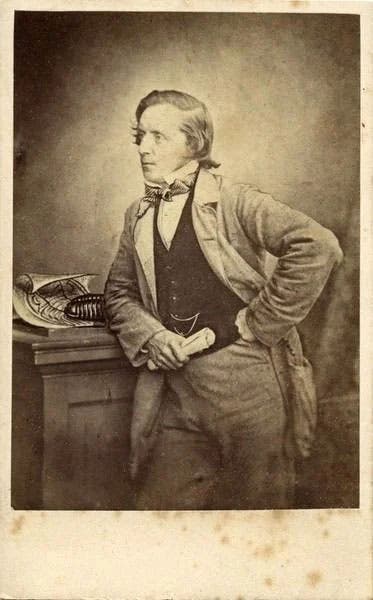

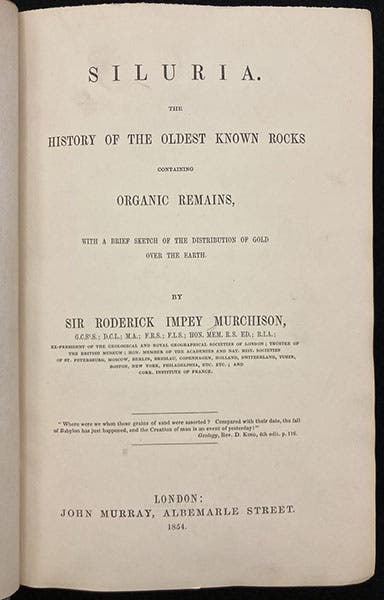

In 1846, Salter was hired away from Sedgwick to become an assistant paleontologist for the Geological Survey of Great Britain, which was headed up by Henry de la Beche, and for whom Edward Forbes had recently come to work as Chief Paleontologist. Salter was Forbes' assistant, and Forbes was quite pleased with his work. With steady employment, Salter married (one of the daughters of Sowerby), and began a family The Survey had its own Museum in London, and Salter was set to identifying the many Paleozoic fossils there, about which Forbes knew little. He also continued to assist Sedgwick in his work, and he provided descriptions and illustrations for Murchison's second book on the Silurian system, a more modest and accessible work called Siluria (first and fifth images). It was published in 1854, and reissued often thereafter. We have two editions, including the first, in our collections. In the preface to the first edition, Murchison thanks Salter for his contributions (fourth image)

In 1854, Forbes left for Edinburgh, and his job at the Survey was split up. Thomas H. Huxley came on board as lecturer at the School of Mines, run by the Survey, and Salter was given the rest of Forbes’ job as chief paleontologist. Murchison became Survey Director in 1855. This is where things began to go sideways for Salter. Salter could not manage people. He was great in the museum, but a complete washout in the office. He was also something of a religious fanatic, which irritated many of his colleagues. And as the British would say, he did not know his place. Murchison and Sedgwick were now at odds, as Murchison tried to appropriate the Cambrian system into his Silurian system (calling it lower Silurian), and at a meeting of the Geological Society in 1854, Salter actually attempted to adjudicate the rift between the two, a professor and a wealthy collector, as if he were their social equal. The fellows of the Society were most amused at such effrontery.

Unable to manage his assistants, Salter’s responsibilities were gradually reduced by Murchison, until eventually he managed no one but the fossils. And Salter began to show signs of mental instability. Some of his colleagues thought he ought to be committed to an asylum. Huxley grew impatient with Salter, and ultimately gave Murchison an ultimatum – either Salter goes, or he would. In 1863, Murchison let Salter go from the Survey.

By this time, Salter had 7 children to feed, and he was desperate for work. Sedgwick gave him some, but he needed more income. He did have friends, and they tried to help out financially, but Salter never did find another permanent job. As he grew increasingly manic, his wife left him and took the children. On Dec. 15, 1869, Salter boarded a Thames ferry with one of his sons. He gave the lad his gold watch, which had been given to him by Sedgwick, and then walked around the deck until he was out of sight, and jumped overboard, and drowned. It was a sad ending to a sad life.

There were probably lots of John Salters who lived out similar difficult lives in Victorian England, trying to earn a living as a naturalist, when there were few paying positions, and those were at a poverty level. Fortunately, Salter’s career drew the attention of a perceptive historian of science, James Secord, who wrote about Salter in his Controversy in Victorian Geology: The Cambrian-Silurian Dispute (1986), and in a separate article on Salter that he published the previous year. We have both publications in the Library.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.