Scientist of the Day - John William Dawson

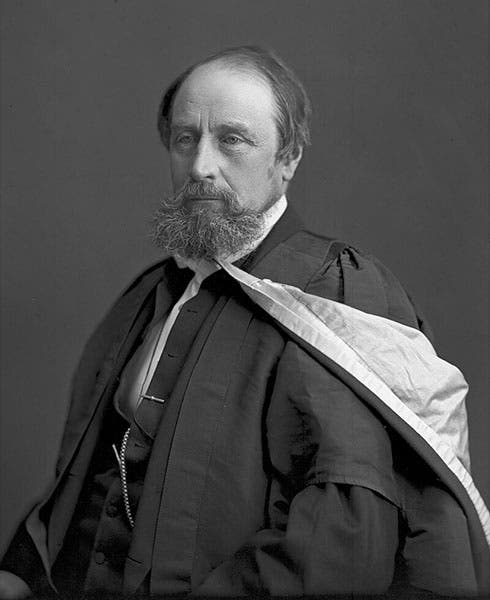

John William Dawson, a Canadian geologist, was born Oct. 13, 1820, in Pictou, Nova Scotia. Dawson went to Scotland to study geology at the University of Edinburgh, and then returned in 1842 with the distinguished Scottish geologist, Charles Lyell, who wanted to take a closer look at the Joggins Formation in northwest Nova Scotia, along the Bay of Fundy. The formation was Carboniferous in age, and had long been known as a source of coal, but several recent investigators had noted the presence of fossilized tree trunks, some still upright, among the sedimentary layers at Joggins. No one at the time knew how coal was formed, so Lyell was eager to view Joggins firsthand, and see if it might confirm (or refute) his belief that coal formed from decayed vegetation, and not under the sea, as most others believed. Young Dawson was only 21 years old at the time and had no axe to grind; he was just curious, and glad perhaps for an excuse to go home.

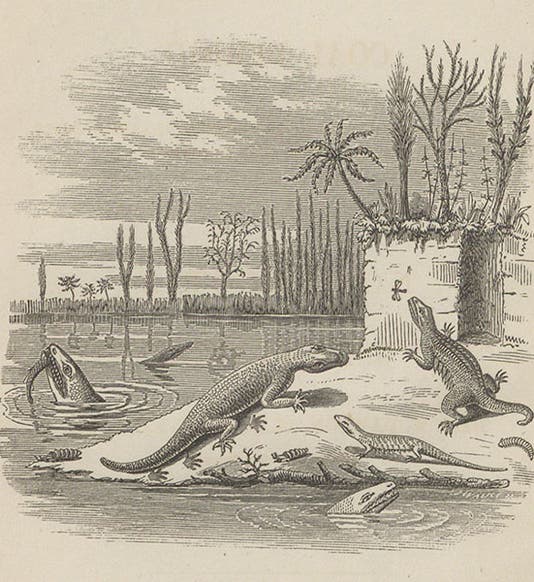

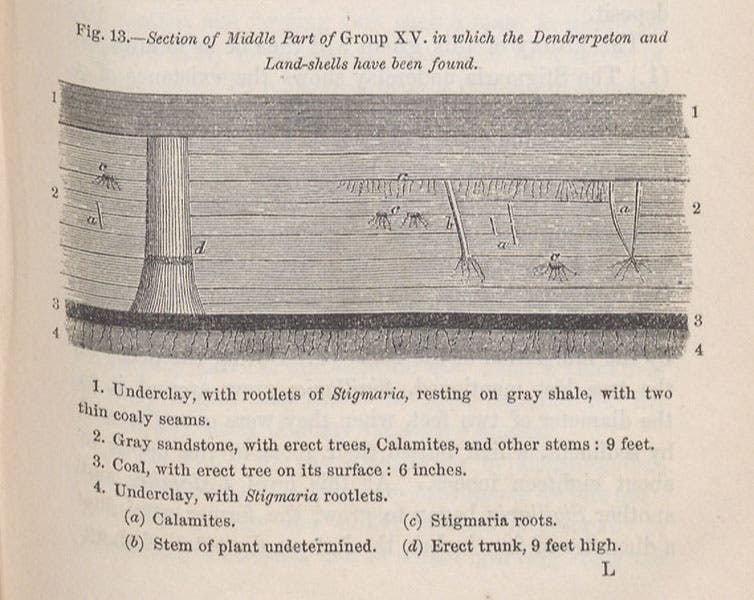

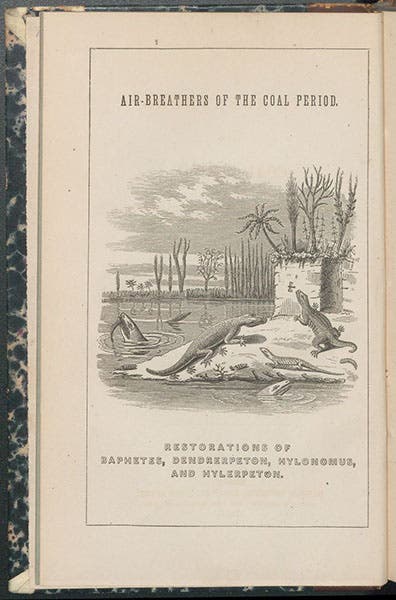

Lyell was happy to find evidence that the coal formed from the forests that once grew there, for which the tree trunks provided evidence (fourth image). Lyell returned to Joggins in 1852, and again met up with Dawson, who had stayed in Nova Scotia. The two mapped the Joggins Formation in detail, and Dawson found, in one of the semi-petrified tree trunks, the bones of what looked like an amphibian, the first Carboniferous amphibian ever found (fifth image). It was named Dendrerpeton (by Richard Owen, who had no business naming it, since he had nothing to do with finding it). Lyell went back home and never saw America again, but Dawson remained and became professor of geology at McGill University in Montreal, and he returned to Joggins again and again. He found other species of amphibians, including one in the oldest strata at Joggins, which he named, after Lyell, Hylonomus lyelli. You can see both Dendrerpeton and Hylonomus on the frontispiece to Dawson's Air-breathers of the coal period (1863; first image), which we have in our collections, although I cannot tell you which is which, since the only captions, below the wood engraving (sixth image) give no indication what label goes with which reconstructed specimen.

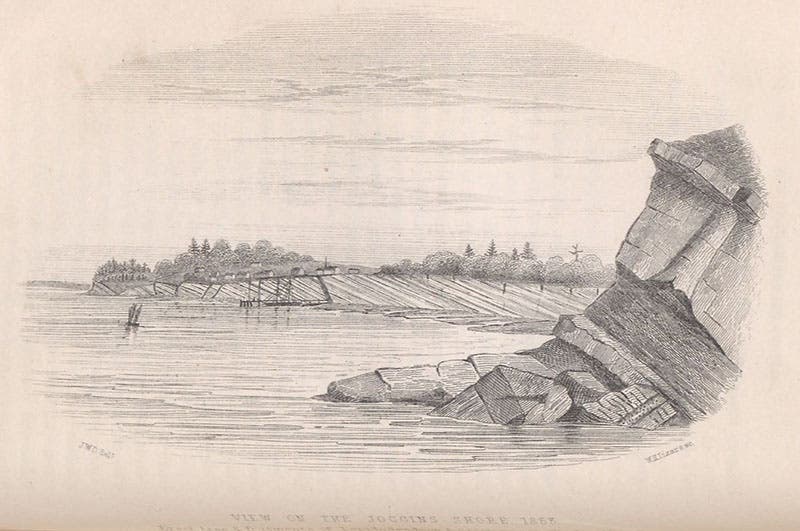

Earlier, soon after his 1852 trip to Joggins, Dawson had published an entire book, Acadian Geology, about the geology of Nova Scotia. We have that in our collections as well. Our scenic view of Joggins (third image) and the two wood engravings depicting a section of Joggins with standing tree intact (fourth image), and the jaw of Dendrerpeton (fifth image), were taken from this book.

In 1865, Dawson claimed to have found evidence of microscopic life in the Laurentian Formation, considered some of the oldest rocks on earth. He published his drawings in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London in 1855 (seventh image) He called his tiny organisms Eozoön canadense. Lots of people, including Charles Darwin, were excited by this, but it turned our that what looked like cells under the microscope were in fact crystal formations that had an inorganic origin. This has happened many times to many people, including most recently, the first investigators of the meteorite ALH 84001, which bounced all the way to Earth from Mars, and which one scientific team, in 1996, claimed held nano-bacteria from Mars. The life-life fossil organisms they identified, as with Eozoön canadense, turned out to be inorganic in origin.

Dawson was precocious in some of his geological conclusions, and a bit reactionary in others, as he resisted Darwinian evolution right up to his dying days. He was not alone. But he deserves credit for his finds at Joggins. Because of the discoveries by Dawson and Lyell, Joggins was listed in 2008 as World Heritage Site #1285, Joggins Fossil Cliffs, the best place in the world to find Carboniferous fossils. You can see quite a few modern photographs of the formations, and a map locating Joggins in Nova Scotia and eastern Canada, on the WHS webpage.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.