Scientist of the Day - John White

John White, an English painter and colonist, was born sometime in the 16th century, but we know not when. He had a daughter Eleanor, but her birthdate is also unknown, as is the date of her marriage to Ananias Dare, a tile-layer. The couple had a daughter, and fortunately, the date and place of birth of the grandchild are matters of public record, so we now have a reason to talk about John White on this day. The child was born Aug. 18, 1587, in the newly founded Roanoke colony on Chesapeake Bay, in what was then called Virginia. John White's granddaughter was named Virginia Dare.

You may have learned about Virginia Dare in grade school or middle school; you were certainly told about her if you attended an American school. Virginia was the first person of English descent born in the American colonies. The Roanoke colony was short-lived – it was there in 1587, when John White, the governor and new grandfather, was sent back to England for supplies. When he returned in 1590, the colony was gone with very few traces. White was delayed in his return to Roanoke by the threat of the Spanish Armada, which prevented all shipments from England to the New World for several years. So we don't know if Virginia and her mother and father survived Virginia's third year, although statues of a full-grown Virginia dot the southeast.

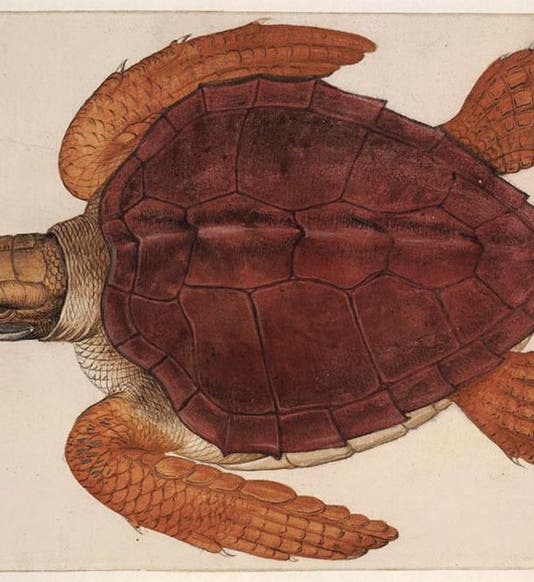

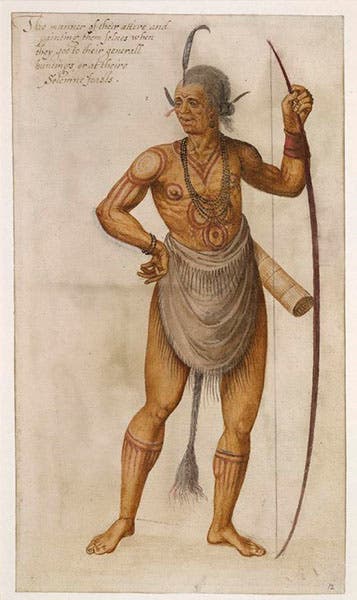

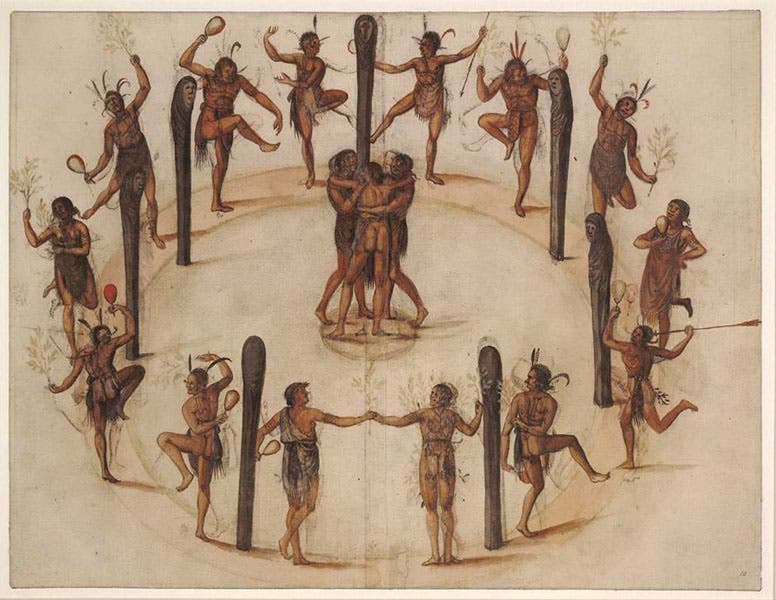

John White, however, did survive. Before the loss of his family, he had painted watercolors of New World animals, plants, the native Algonquins, and various aspects of their lifestyle. He brought these back with him when he returned for provisions, and the watercolors survived. In fact, they still survive, one of the treasures of the British Museum in London. Our first image shows a White drawing of a loggerhead turtle, one of his many natural history drawings, and we follow with a watercolor of the local chieftain, his wife and daughter, a couple dining (“Theire sitting at meate”), and a native dance. These are the first depictions of New World peoples that were made without preconceptions, capturing their culture without judgement. The British Museum has 236 John White related items, many of them watercolors, and you can find thumbnails of all of them on this webpage (click on “Related Objects” at top left.

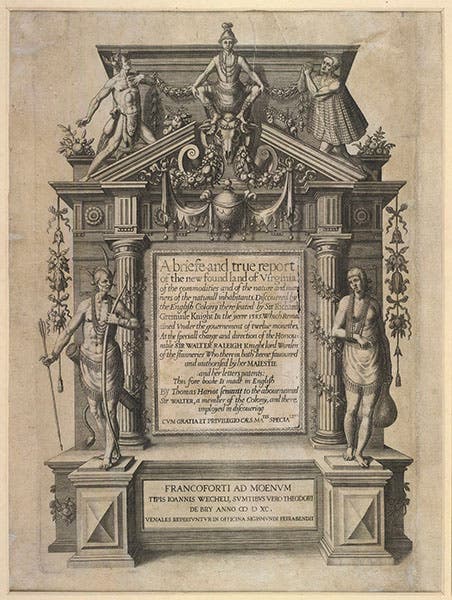

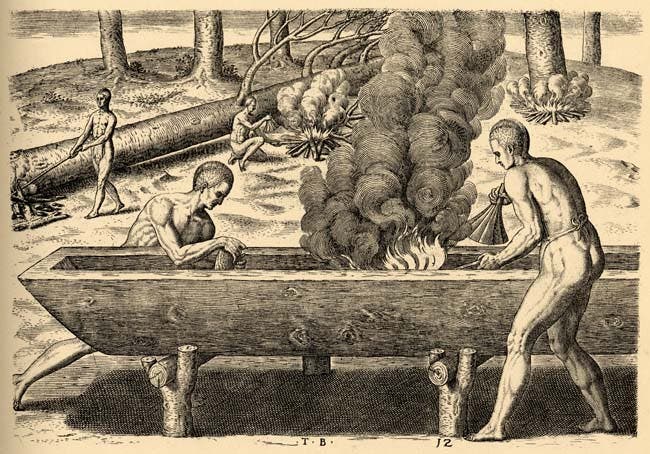

All this artwork might well have disappeared with White (we know no more of his whereabouts after 1593); fortunately, the German engraver and publisher Theodor de Bry was looking for images to illustrate the first volume of his Great Voyages, and somehow, he heard about White and his drawings. Some kind of a deal was made, and many of White's watercolors were converted to engravings and appear in that first volume, which was titled: A Briefe and True Report of the new found land of Virginia (1590), with text by Thomas Harriot. We include here the engraved title page (sixth image), featuring White’s drawings of the chieftain and his wife (the child was left on the engraving room floor). I particularly like a de Bry engraving showing the crafting of a dugout canoe (seventh image), not only because making a boat in such a fashion was unheard of to Europeans, but because the White watercolor on which it was based does not survive, so this is the only evidence we have of this particular White observation. We do not own Harriot’s book, so our images of de Bry’s engravings were drawn from online sources.

In an unexpected leap of vision, White wondered whether early Europeans, such as Britons or Picts, might have had a culture like the Algonquins he had studied, and he made several speculative drawings depicting what these ancient peoples might have looked like. Since it was customary in 1590 to portray ancient Europeans as people just like ourselves, civilized and cultured, White's daring depictions of primitive ancestors are considered to mark the rebirth of the idea of primitivism in the West, helped out by the fact that De Bry included engravings of Picts and Britons, made from White’s drawings, at the end of A Briefe and True Report.

When the Wedgwood pottery firm in 1985 celebrated the 400th anniversary of the first attempt to found a Roanoke colony (in 1585), they issued special commemorative table ware. The images on the plates and bowls were taken from de Bry’s engravings of John White’s watercolors; we show you one (ninth image), which you will now recognize.

Surprisingly, for an artist, John White left no self-portrait behind among his watercolors, so we have no idea what he looked like in his own eyes. But we are fortunate to know what he saw through those eyes when he looked at the rest of the world, especially the New World. His watercolors are a unique treasure.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.