Scientist of the Day - John Whipple Potter Jenks

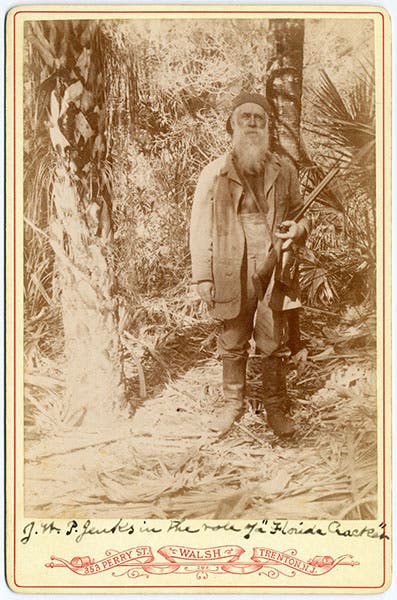

John Whipple Potter Jenks, an American naturalist and museum curator, died Sep. 26, 1894, at the age of 75. Jenks was born in West Boylston, Mass. attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and then, after a few footloose years, married into a wealthy family in Middleborough, Mass, and became, through his father-in-law’s influence, principal of Peirce Academy, a post he held for 23 years, until 1871. Then he quit and took a job – I think there was a salary involved, but maybe not – as curator of a yet-to-be-assembled natural history museum, to be housed in Rhode Island Hall on the Brown campus. He acquired specimens, some from a hunting trip to Florida in 1874, and he definitely learned taxidermy somewhere, for he taught a course at Brown on taxidermy. A wonderful group portrait shows the class posed on the steps of Rhode Island Hall with their homework in hand, and Jenks standing at the back, beaming inside, one supposes (first image).

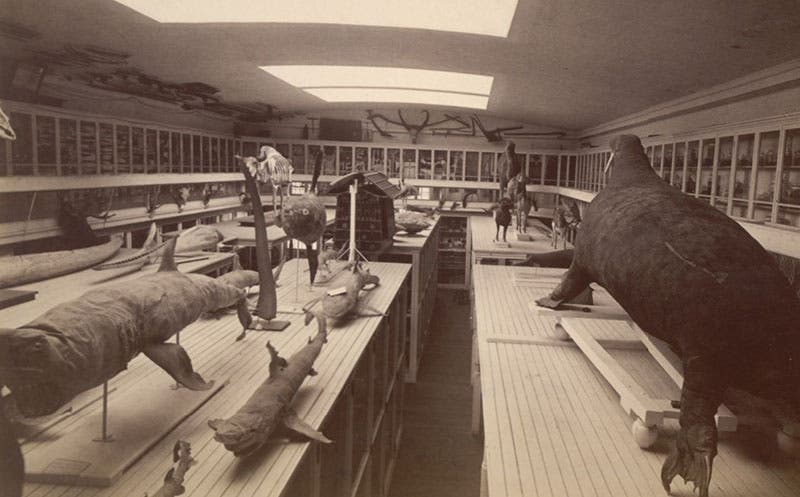

The Jenks Museum of Natural History and Anthropology grew to be quite something, if the photographs don’t lie. One photo (third image) shows the first floor with its multiple standing cases, and another shows us what appears to be the tops of the display cases, kind of a makeshift second floor, with a variety of sharks (and a giant sunfish) scattered about (fourth image). There were apparently some 50,000 specimens in place by the time Jenks was done.

Jenks’ curatorship ended surprisingly abruptly. He had just eaten lunch with friends, on this day in 1894, and dropped by Rhode Island Hall to pick up something, sat down suddenly on the front steps, and died, just like that, a man in apparent perfect health just moments before. It was quite a shock to all concerned.

The museum died a slower death. With no one in charge, it gradually grew more and more disheveled and disorganized, until finally the administration shut it down in 1915 and moved everything into storage. Thirty years later, some misguided soul decided it was high time to clean out the storage areas, and nearly all of the specimens were hauled to the dump. Should I add “unceremoniously,” as journalists always do? The Jenks Museum was history.

Well, not quite. Around 2013, a group of Brown students, motivated by faculty members who knew the story of Jenks’ Museum, decided to restore part of it, however briefly, in conjunction with the 250th anniversary of Brown University. They organized an informal group, the Jenks Society, and pored over records and located odd pieces that had been stored elsewhere, or loaned out, and had escaped the dump. They must have had a photo of Jenks’ office and workroom (I could not find one), for they recreated it for their exhibition (fifth image). And they commissioned local artists to construct “ghost” items, pale white forms, nestled in a closet, of those objects that had been carted away and disposed of. The found objects were displayed in three cases, as you can see in the photos (sixth and seventh images).

The exhibition opened in the late summer of 2014 and ran through the spring of 2015. It was called The Lost Museum, and it attracted some attention at the time, with a story in the New York Times (which provided two of our images). One of the faculty involved with the Jenks Society and The Lost Museum, Steven Lubar, has since written and published a book, Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present (Harvard University Press, 2017), which interweaves the story of Jenks’ Museum with the problems of curating a museum in general. Since it did not come up in my searches for Jenks (because, I suppose, of the unspecific title), I did not learn about it until just now. It looks to be excellent, and I am sure there is material there that I could have and should have used for this post. Perhaps we will revisit Jenks next year, after I have read Professor Lubar’s book.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.