Scientist of the Day - John Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler, an American physicist, was born July 9, 1911. He grew up in Youngstown, Ohio; both of his parents were librarians (as would be two of his three siblings). He attended Johns Hopkins University, where he received his PhD in physics in 1933, then secured several fellowships, one of which allowed him to study with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen. After several years teaching at the University of North Carolina, he accepted an offer from Princeton in 1938 to become an assistant professor in their physics department.

His interest at the time (which would change) was particle physics and quantum mechanics. By 1938, the neutron had been discovered (1932) and the neutrino predicted (1933), and artificial transmutation had been detected (1935). Also, unbeknownst to anyone in the U.S., the atom had been split, by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in Berlin (1938). Particle physics was popular and thriving. Wheeler had already made several important contributions, working with Bohr.

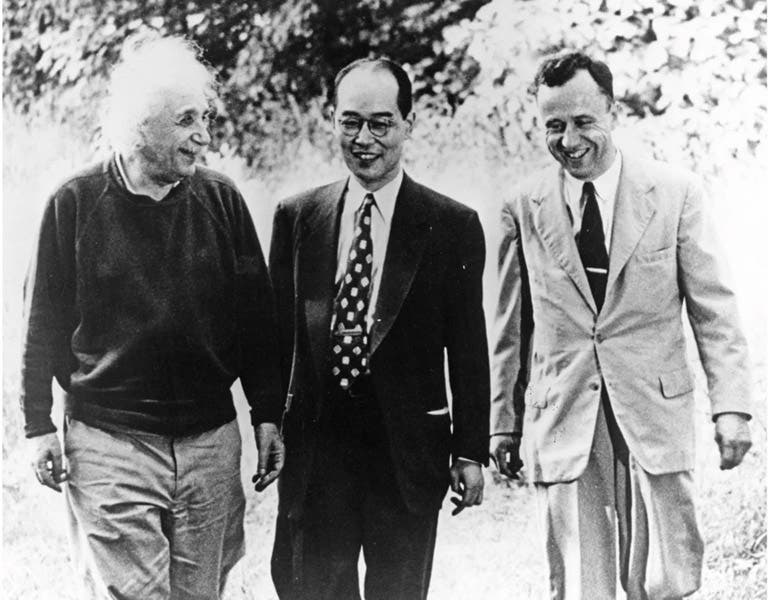

In the fall of 1939, a new Princeton graduate student was appointed to be the TA for Wheeler's course in mechanics, and he was invited to an introductory meeting. His name was Richard Feynman. He was only 6 years younger than Wheeler. Wheeler happened to be engaged in a time-motion study, trying to determine how much time he spent on research, in the classroom, and with students, so as Feynman sat down, Wheeler pulled out and started his stop watch and put it on the table between them. The meeting apparently went well – Feynman was clearly a sharp cookie. At their second meeting, as Feynman sat down, Wheeler pulled out his watch. Feynman then reached into his pocket and pulled out a pocket watch of his own and put it on the table in front of him. Wheeler stared at it for a second, then burst out laughing, as did Feynman, and the two were immediately friends, and would be so for the rest of their lives.

Wheeler tells the story in his autobiography, Geons, Black Holes, and Quantum Foam: A Life in Physics (with Kenneth Ford, 1998) – I don't think Feynmann told it in his two autobiographical narratives. But he did tell a different story involving Wheeler. Wheeler told Feynman it was time for him to lead his first seminar, on a thought experiment the two had done involving electrons moving backward through time. Eugene Wigner was the other physicist at Princeton, and just before the seminar, Wigner told Feynman that he had invited Henry Norris Russell (in his day (which wasn't that day), one of the great American astronomers), John von Neumann (probably the greatest living mathematician), and that Wolfgang Pauli, formulator of the uncertainty principle, who was visiting from Switzerland, would drop by, and by the way, Einstein never comes to our seminars, but this topic interests him, so he will attend as well. Feynman, to his credit, was undaunted and made it through, and fortunately, during the question period, Einstein and Pauli got into an animated discussion, and Feynman was spared further questions. Wheeler was supposed to give a follow-up seminar, working out the quantum-mechanical details, but he wisely never did.

Wheeler was right there on the dock in New York City in January of 1939, when Bohr steamed in from Copenhagen and told American physicists that Germany had split the atom and a weapon might be a possibility (although Bohr himself at first did not think a weapon was feasible). Wheeler went on to work for the Hanford Engineering Works (the branch of the Manhattan Project that built nuclear reactors in the state of Washington to make plutonium for the first atomic bomb). After the War, he returned to Princeton and found his interest shifting to general relativity, in which Einstein was still interested but which appealed to few other physicists, since it did not seem to have an experimental basis. But Wheeler thought it was important, and he left quantum electrodynamics to Feynman and his colleagues, who did not seem to need his help.

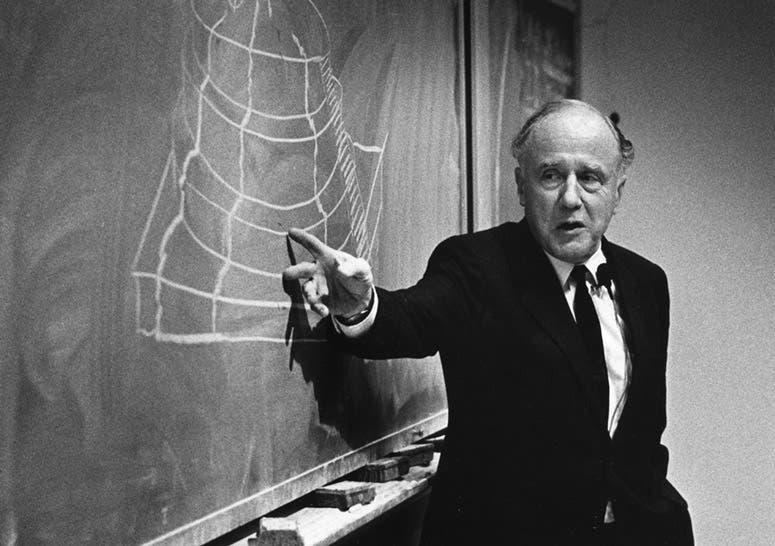

As fortune would have it, the fifties and sixties were a golden age for general relativity, with the prediction and later discovery of black holes. A black hole, an object that has gravitationally contracted to a point singularity and is surrounded by an event horizon, from which no light or radiation of any kind can escape, is a direct prediction from general relativity, a prediction that was first worked out by Robert Oppenheimer in 1939. But no one at the time thought such objects could really exist. Wheeler drummed up renewed interest in the physics of black holes in the 1960s, and even coined the term black hole itself. Wheeler, like William Whewell a century earlier, had a way with words, and is also credited with the terms geon and quantum foam, which you probably will not encounter in your New York Times crossword, and wormhole, which you might. Wheeler, in a lecture, also uttered the memorable phrase, “Black holes have no hair,” a way of pointing out that when anything enters the event horizon of a black hole, its entire personal history is wiped out, except for its mass, charge, and angular momentum.

When Wheeler reached the mandatory retirement age at Princeton in 1976, he pulled up stakes and moved to the University of Texas at Austin, where he worked for another 10 years. He was encouraged to make the move by his wife Janette, with whom he seems to have shared a remarkable marriage (fifth image). She passed away in the fall of 2007, age 96, and as often seems to happen in such marriages, Wheeler died the following spring, also age 96. He never won a Nobel Prize, but he left behind more well-trained physicists than perhaps any other physicist of his generation.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.