Scientist of the Day - John Vaughan Thompson

John Vaughan Thompson, an Army surgeon who dabbled in marine biology, was born Nov. 19, 1779, on Long Island in the United States, while the Revolutionary War was in full swing. When the war was over, he and his family moved back to England, to Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland, where Thompson grew up. The town is on the coast of northeast England, bordered by the sea, and it was probably where Thompson picked up his life-long interest in marine life.

Thompson attended medical school at the University of Edinburgh, where an entire school of marine biologists would arise in the 1820s (see yesterday’s post on Edward Forbes, and an earlier post on Robert Grant), but Thompson was there too early to be affected – his love for marine biology was entirely self-kindled.

Trained as a surgeon, Thompson enlisted in the Royal Army in 1799 and was sent to a variety of overseas posts, such as the West Indies and Mauritius. He apparently pursued natural history on the side, for he published a variety of papers in the Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. Then, in 1816, he was assigned to Cork in Ireland, where he became “Surgeon to the Forces” and, shortly thereafter, Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals.

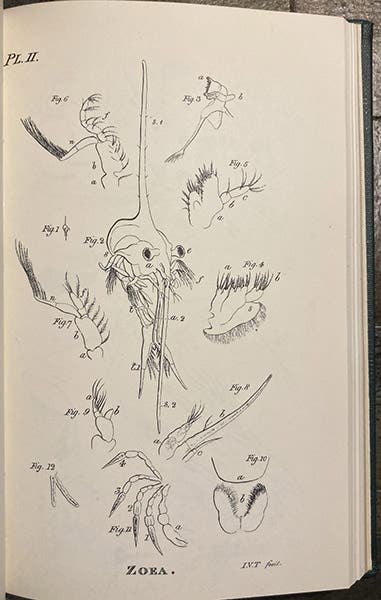

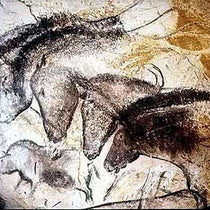

Cork is on the River Lee and not far from Cork Harbour, an estuary almost as rich in marine life as the Firth of Forth at Edinbugh. Thompson seems to have spent a lot of time there, and whenever he crossed the harbor by ferry, he dragged a plankton net from the rail. On one of those occasions, in 1823, he pulled in a tiny creature that was already known to naturalists, who called it a Zoea. It was thought to be a species in its own right. Thompson discovered, by keeping Zoea alive in seawater, that it was actually the larval stage of a crab (fourth image). Crabs, considered to be “higher crustacea,” were not thought to go through larval stages like the lower crustacea, such as insects. Thompson’s was a surprising discovery.

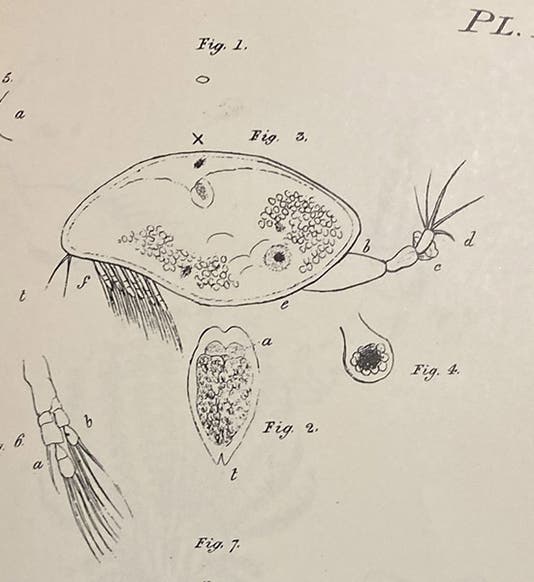

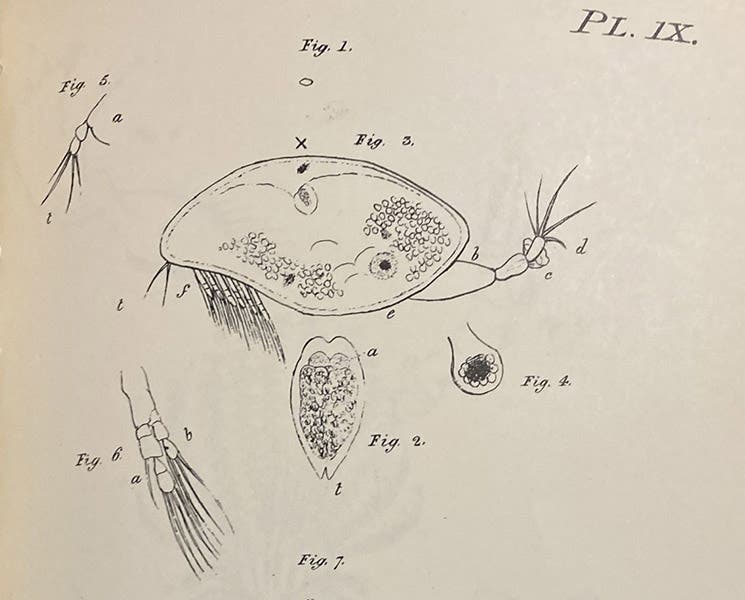

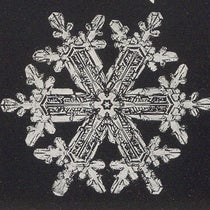

Even more surprising was another bit of plankton, this one unknown to zoologists, and found even before his Zoea, although not explained until much later (first image). This one (or rather its brethren), after years of coaxing, eventually amazed Thompson by fastening itself to the glass tank and metamorphosizing into a barnacle. Barnacles were not even thought to be crustaceans at the time – Georges Cuvier had placed them in with the mollusks, since they were not segmented and had a shell (of sorts). Thompson not only discovered the larval stage of the barnacle, but, since the larvae were clearly segmented crustaceans, also realized that the Cirripedia, as Linnaeus called barnacles, are really crustaceans.

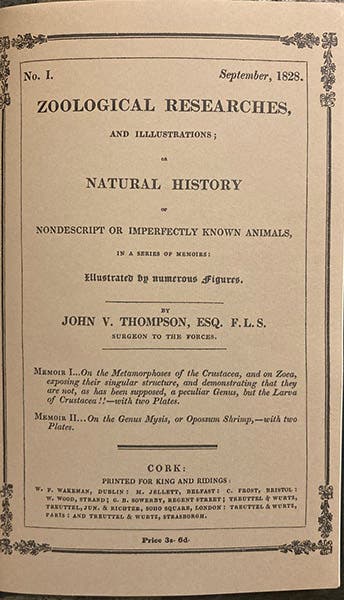

Thompson published the results of his work on crustaceans and their larval stages in a set of memoirs, printed in Cork from 1828 to 1834, called Zoological Researches and Illustrations: or, Natural History of Nondescript or Imperfectly Known Animals, in a Series of Memoirs. The set is incredibly scarce – I have never seen a copy – and I was only able to read it because the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History issued a facsimile in 1968, from which I drew our images. It was apparently not so scarce in 1831, for Darwin took the first Memoirs with him on the Beagle voyage, and must have had the later Memoirs sent to him, because he eventually had the complete set of 5 numbers. Perhaps the work was instrumental in suggesting to Dawin, 15 years later, that the world needed an even more thorough study of barnacles. Darwin’s own volumes appeared in 1851 and 1854 (see our post on Darwin’s barnacles). There were lots of comments on barnacles between those of Thompson and Darwin – Richard Owen, for example, denied that barnacles are crustaceans in 1843 – and I think we have every work relevant to barnacle anatomy and taxonomy in our collections except Thompson’s. That set of Memoirs would be a wonderful acquisition, if we could find a copy on the market.

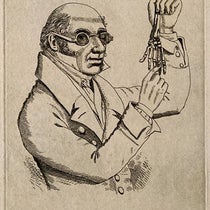

Thompson moved to Australia around 1836 and we hear no more from him on crustaceans. But he did have a portrait painted, in watercolor, which is in the Port Macquarie Museum in New South Wales (second image). It is the only known portrait of Thompson.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.