Scientist of the Day - John Turberville Needham

John Turberville Needham, an English microscopist, microbiologist, and Catholic priest, died on Dec. 30, 1781, at the age of 68. Needham is best known for a series of experiments that he published in 1748, in which he claimed that animal life could be spontaneously generated in flasks of decayed matter, even when it had been boiled and sealed. The veracity of these experiments was attacked by Lazzaro Spallanzani in 1765, who claimed that Needham simply hadn't sterilized his broth long enough, and that when done properly, no living organisms appeared in the flasks. However, we are going to defer discussion of the Needham-Spallanzani debates for a later time, and instead discuss here an earlier book by Needham that is often overlooked, and which we have in our History of Science Collections. It is called: An Account of Some New Microscopical Discoveries, and consists of 126 pages of text and 6 folding plates at the end.

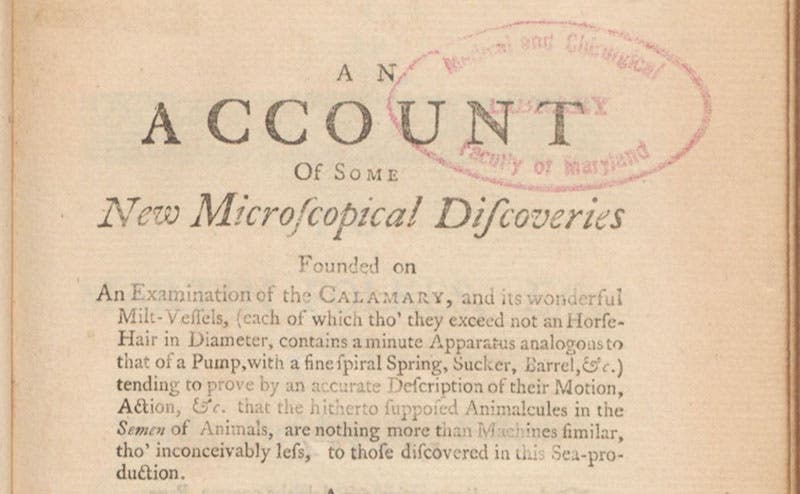

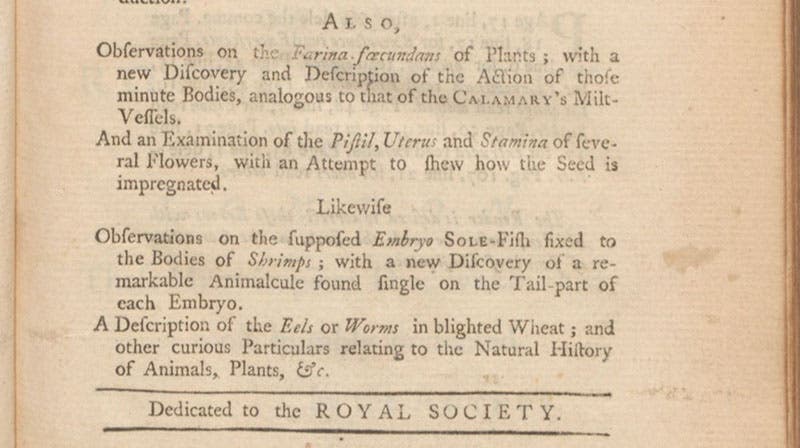

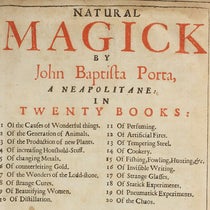

The first point I would like to make is that the title I used for Needham’s book is a mere shadow of the title that Needham used (second image). I thought I would show you details of the title page (third and fourth images) so that you can read it. It is, in fact, a table of contents disguised as a title, and broken up only by “founded on,” “also,” and “likewise.” It is rather more useful than most title pages, as, having read it, you know exactly what to expect in the book: discussions of the milt-vessels of calamari, the stamens and pistils of lilies, embryo sole-fish and their animalcules, and eels found in blighted wheat. Interestingly, in all that verbiage, Needham forgot to mention his observations on barnacles, which we will briefly bring up.

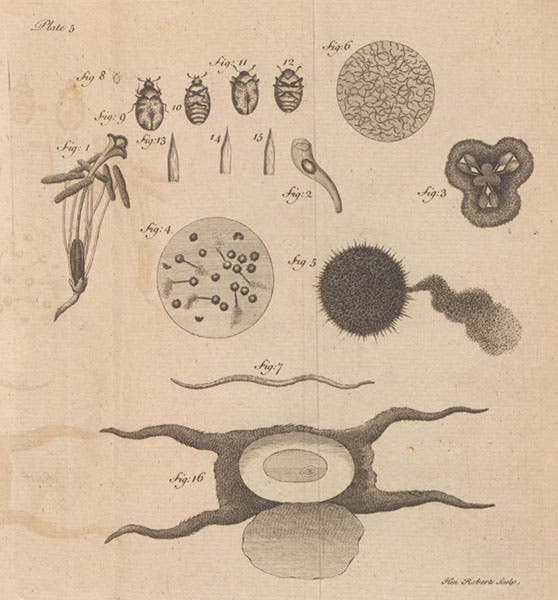

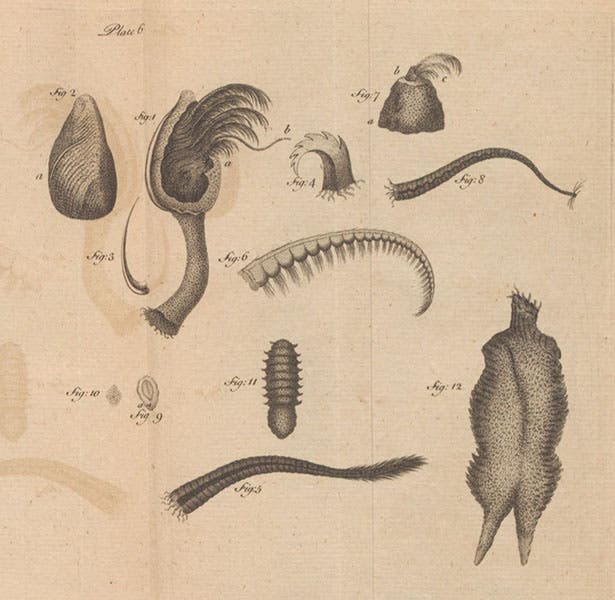

Microscopic examination of living things had begun in the 1660s with the work of Robert Hooke, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Jan Swammerdam, and several others, but it had not progressed much further by Needham’s time. Daphnia had been observed, and a few copepods, but not much more. So when Needham examined sole-embryos on shrimp, and then found a 16-legged “animalcule” on the sole-embryo, he was practicing a kind of microbiology that had few precedents. The idea that certain kinds of shrimp produce embryos that eventually grow into soles (the fish) was a fisherman’s tale from France and England that Needham was examining (and did not prove or disprove). In his sixth plate (sixth image), of which we include a detail (seventh image), he shows the supposed sole-embryo, unmagnified, as fig. 9, and denotes the hanger-on with the letter “a,” and then in fig. 11, he depicts the animalcule as seen through the microscope. I have no idea what it really is, as I did not find any mention of it in the literature on 18th-century microscopy, although Needham is insistent that it was found on every single sole-embryo he examined.

The other, more recognizable, creature found on plate 6 (sixth image) is the barnacle, two of which are depicted as figs. 1 (closed up), 2 (cut-away), and 7 (a smaller barnacle). Even though he did not mention barnacles on his title page, I noticed them immediately, because the 19th-century’s most famous naturalist, Charles Darwin, published four volumes on barnacles (1851-54) before he got around to composing On the Origin of Species. I do not know if Darwin was aware of Needham’s drawings.

You can see at the bottom of our fourth image that Needham dedicated his book to the Royal Society of London. The ploy worked; he was elected as a fellow in 1747, and was supposedly the first Catholic priest to be so selected.

We will continue our discussion of Needham on his birthday, Sep. 10, when we will look at the spontaneous generation affair of Needham and Spallanzani.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.