Scientist of the Day - John Theophilus Desaguliers

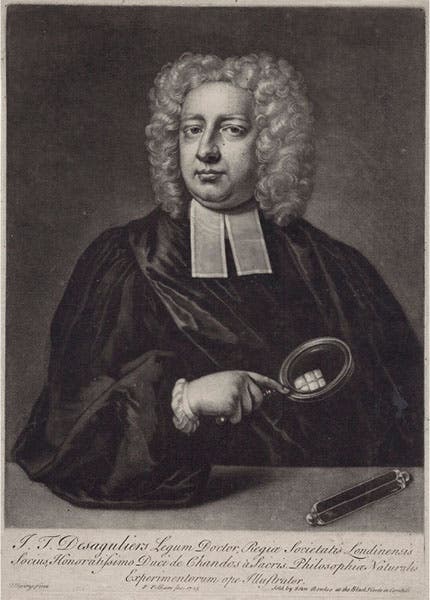

John Theophilus Desaguliers, an English experimental physicist of French origin, was born Mar. 12, 1683. He came from La Rochelle to England when he was young, apparently distinguished himself with his intelligence and industry, and made it to Oxford, from which he graduated in 1709. He liked building machines, especially those for scientific demonstrations, and he came to the attention of Francis Hauksbee the elder, who was the paid demonstrator at the Royal Society of London. Every week, for ten months of the year, Hauksbee would design and build an experiment to perform at the weekly meeting of the Royal Society. Desaguliers appears to have helped him considerably in this enterprise, so when Hauksbee died suddenly in 1713, Desaguliers was chosen to succeed him. Isaac Newton, who was president of the Society, seems to have taken a liking to young Desaguliers, who was forty years his junior, and arranged for Desaguliers to be elected Fellow of the Society in 1714, which was not customary for mere “mechanics.”

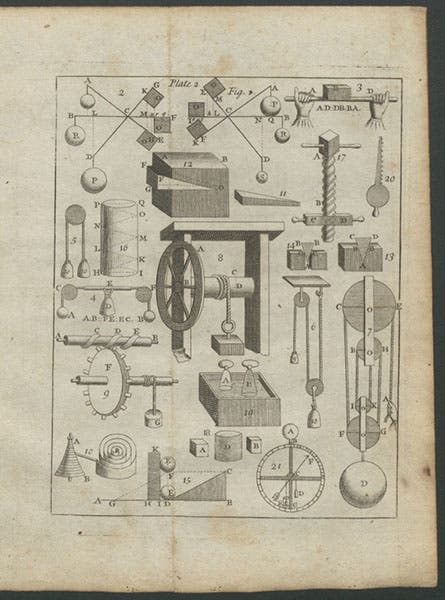

There was a vogue in early 18th-century England for public demonstrations of experimental science – people wanted to see air pumps, electrical machines, and Magdeburg spheres in action. Into the breach leapt many lower- and middle-class artisans, trying to make a living by satisfying this public desire for science education. Desaguliers was one of those, and he paired his work for the Royal Society with public lecture courses, in which he would demonstrate a variety of devices, most of which he made himself. Desaguliers was apparently very good at this. His courses became more involved and were well attended by a paying public. He drew up a set of lecture notes, and in 1717, he had them printed up for distribution to those who attended his classes and paid their enrollment fees. He also prepared 10 engraved plates with hundreds of figures to illustrate the notes. He had no intention of publishing these for a general readership, because they were his bread-and butter. These privately-printed notes are quite scarce; we do not have a copy, but there is one in the Whipple Library at Cambridge University, the title page of which you can see here.

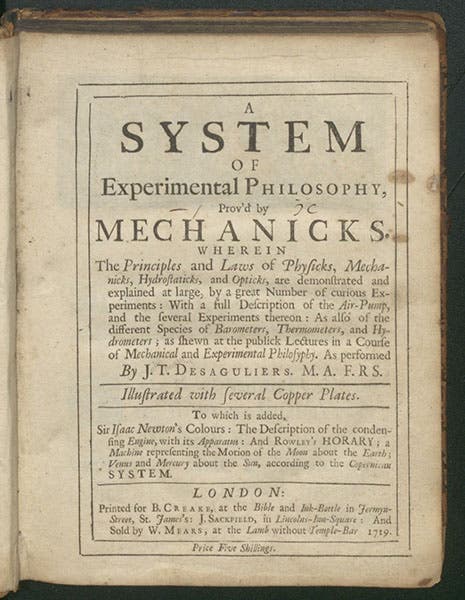

In 1719, one of Desaguliers’ students took his set of notes and engravings to a printer and had them printed up for public sale. Desaguliers’ name was on the title page, with the title A System of Experimental Philosophy, Prov’d by Mechanicks, but he was not involved in the enterprise, and he was furious when he found out about it. He angrily confronted the printers, who were apologetic and offered to make amends. Making the best of the situation, Desaguliers accepted financial compensation, and the printers agreed to let Desaguliers prepare a list of corrections (an errata sheet), which was extensive, since the book was printed hurriedly, with no competent editor. Much of the print run had already been sold, but the copies that remained were graced with a new title page, a preface by Desaguliers, and the errata sheet. The new title was: Lectures of Experimental Philosophy.

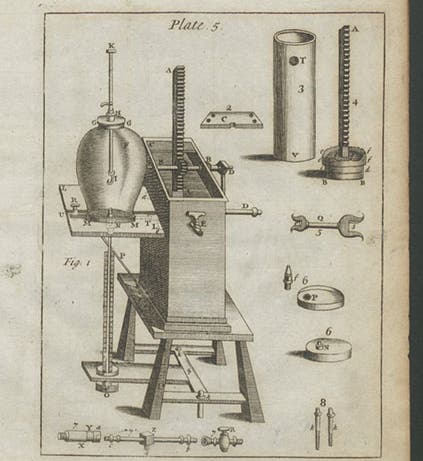

Our copy has both title pages (third and fourth images), which makes it confusing for librarians and bibliographers, as well as the errata sheet and the ten engravings. We illustrate this post with some of the engravings, since they demonstrate the experimental breadth of Desaguliers’ courses. Our first image shows an air pump (which we would call a vacuum pump), built in the manner of Robert Boyle, which was used in a number of the demonstrations, according to both title pages. Another engraving (fifth image) shows some of the so-called “simple machines” – pulley, screw, wedge – knowledge of which was basic to experimental physics.

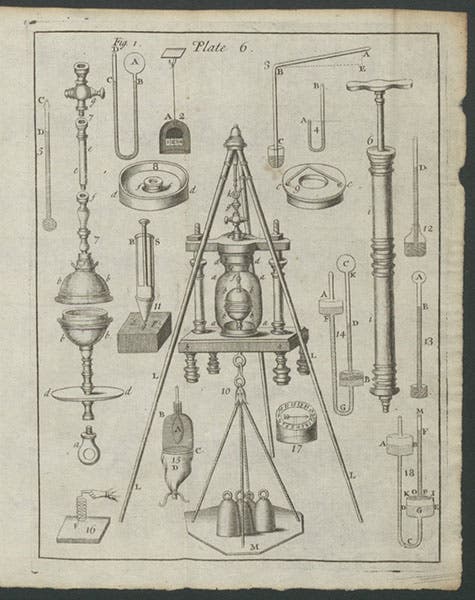

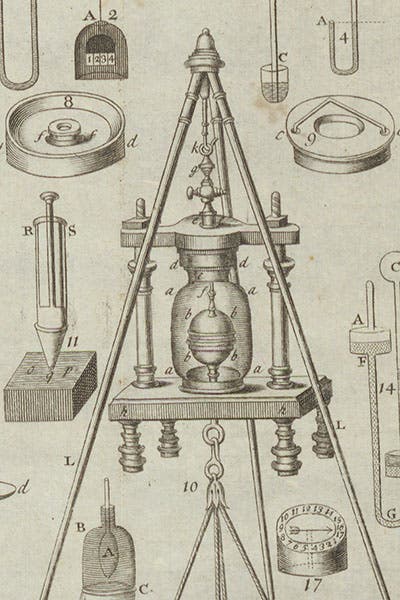

The most interesting engraving (sixth image, below, with a detail as the seventh image) depicts an elaborate set of apparatus for demonstrating the experiment of the Magdeburg spheres, first performed by Otto von Guericke in 1654 and often repeated by later experimenters. In the classical experiment, air was evacuated from two hemispheres, which remained held together by atmospheric pressure and could not be pulled apart even by two teams of horses. When air was let into the joined hemispheres, they fell apart easily. The experiment demonstrated the weight of the atmosphere and the reality of atmospheric pressure. You can see an engraving of the original demonstration at our post on Guericke.

In Desaguliers’ improved version, the hemispheres, which are small, are themselves sealed inside a glass chamber, and weights are suspended from the lower hemisphere, substituting for the horses. Now, when air is evacuated from the jar, the air pressure is gradually removed, and the hemispheres, still evacuated, will be pulled apart by the weights. It must have been quite something to see this experiment performed by Desaguliers in one of his classes.

Desaguliers would go on to have a long and prosperous career as an experimental demonstrator, writing more of his own books and translating those of other experimenters on the Continent. Perhaps we will discuss some of these later works, which we have in our collections, on another occasion.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)