Scientist of the Day - John Henslow

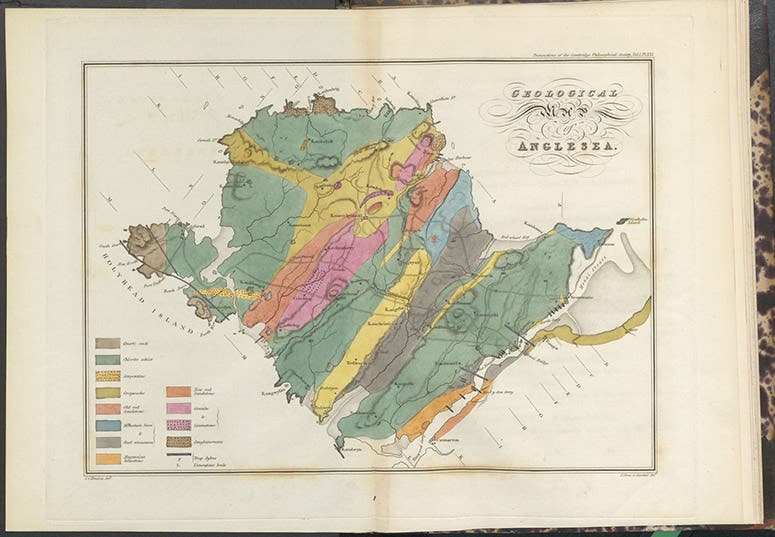

John Stevens Henslow, an English botanist, was born Feb. 6, 1796. Henslow was a professor at Cambridge University; he started out as a geologist, and one of his first papers was on the geology on Anglesea, which he published in the first volume of the Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society in 1822, with 7 handsome plates, including a hand-colored geological map of the island (second image). However, Henslow also loved to collect and study plants, and he soon gave up mineralogy and geology and concentrated on botany.

Geological map of Anglesea, hand-colored engraving of a map by John Stevens Henslow, included with his article, “Geological description of Angslesea,” Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, vol. 1, 1822 (Linda Hall Library)

More significantly, perhaps, Henslow was the most important scientific influence on Charles Darwin in his pre-Beagle days, according to Darwin himself. Darwin met Henslow in 1828, after he had enrolled at Cambridge, and he was soon taking long walks with Henslow and being invited to the Henslow household for dinner. Henslow taught Darwin the important minutiae of being a scientist – how to observe, dissect, use a microscope, take notes. It was Henslow who in 1831 recommended Darwin for the position of "captain's companion" to Robert Fitzroy on HMS Beagle (after Henslow and several others had declined the opportunity). It was Henslow to whom Darwin directed crate after crate of specimens, sent home from various Beagle ports-of-call, accompanied by many letters.

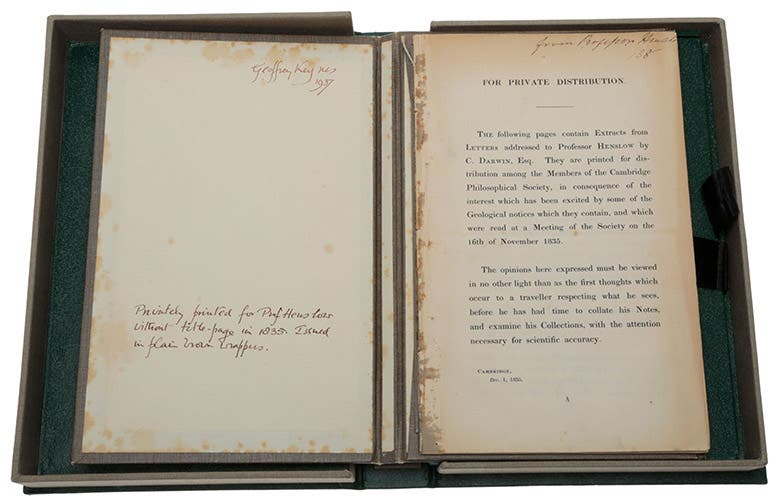

In 1835, Henslow extracted about 30 pages of notes from 10 of Darwin’s letters and arranged for them to be privately printed for distribution to the members of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. The publication is dated Dec. 1, 1835. Some of the extracts were read to a meeting of the Society, and a selection was also read to the Geological Society of London by Adam Sedgwick, professor of geology at Cambridge. Darwin was unaware of any of this activity until he received a letter from his sister, announcing the excitement running through the Shrewsbury household in the aftermath of Henslow’s publication (Darwin’s father read the pamphlet and was most impressed, for the first time realizing that Charles was not just frittering his life away). The 1835 Henslow pamphlet is one of the rarer bits of Darwiniana and does not come up for sale or auction very often; we do not have it in our library. A copy is now on the market, offered by Sophia Rare Books in Copenhagen, a copy that was not only signed by Henslow, but later owned by the great bibliographer, Geoffrey Keynes; it is the source for our third image.

Because of the pamphlet and its wide circulation, when Darwin returned to England in the fall of 1836, he found himself mildly famous in natural history circles, much to his great surprise (and delight), which greatly eased his entrance into scientific society. Henslow was fully responsible for that. Darwin's best friend, Joseph Hooker, later married Henslow's daughter, so the Henslows remained in Darwin's extended circle for a long time, although Henslow moved from Cambridge to Hitcham in Suffolk in 1839 (without resigning his professorship, a neat trick) and took up a new calling as parish rector.

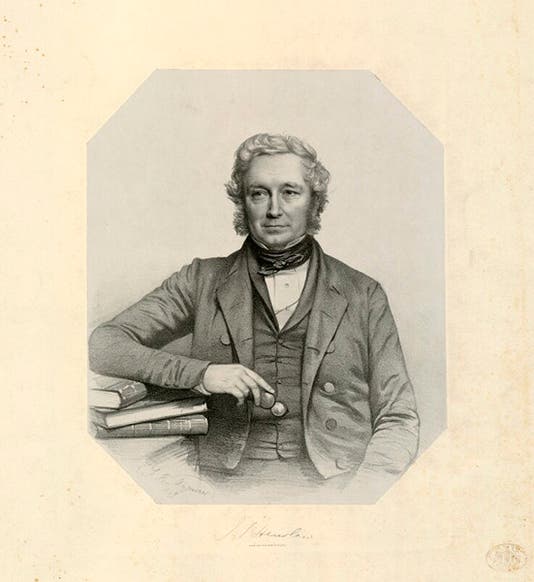

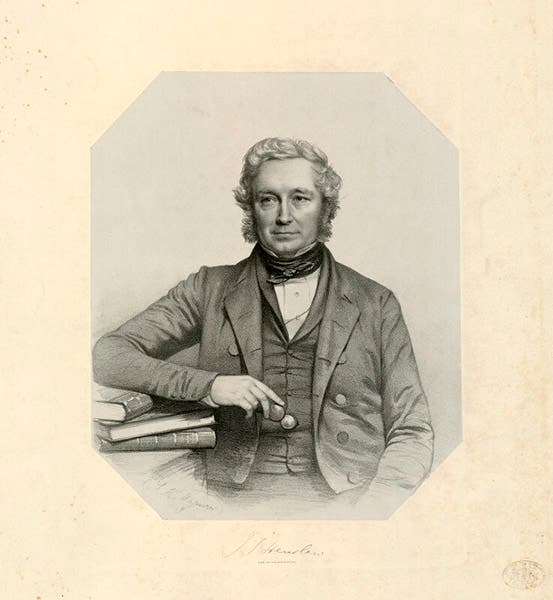

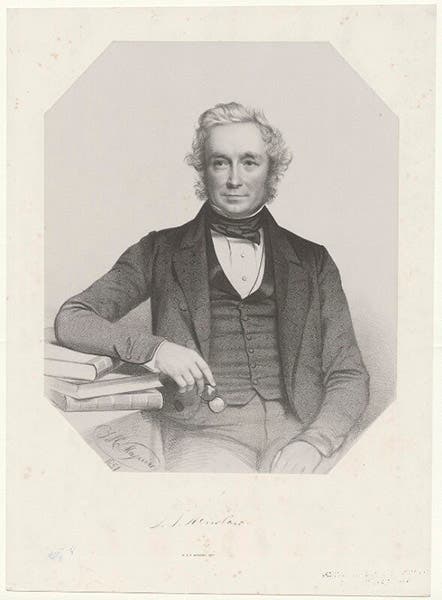

In 1849, the portrait artist Thomas Maguire did a large lithograph portrait of Henslow that captures much of what Darwin admired about Henslow (first image). This was one of a series of at least 64 portraits that Maguire did of Victorian scientists under a commission from the Ipswich Museum (I say “at least” because the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia (ANSP) has a collection of portraits that contains 64 of Maguire’s Ipswich lithographs). Curiously, Maguire did a second portrait of Henslow in 1851 (fourth image), which is the one most often reproduced, but it is less charming, in my opinion, than the 1849 version, where Henslow’s eyes have a mischievous, sardonic look. The ANSP has only the 1849 portrait, but the National Portrait Gallery in London has both.

We have shown many Maguire portraits in this series; he is by far my favorite portrait artist, at least with respect to scientists. You can see some of these at our entries on Charles Darwin, Robert Grant, Prideaux John Selby, Joseph Dalton Hooker, George Busk, and Henry De la Beche – the De la Beche being the only original Maguire portrait we actually own.

Henslow’s last act of note was to chair the special session of the 1860 Oxford meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where Thomas Huxley and Bishop Wilberforce famously debated Darwinian evolution. Henslow died the next year, on May 16, 1861, at his home in Hitcham. He is buried in the graveyard there, with a tombstone befitting his modest but influential character (fifth image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.