Scientist of the Day - John MacEnery

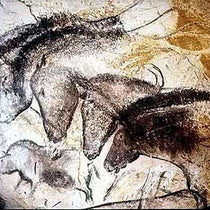

John MacEnery, an English cleric and amateur cave sleuth, was born Nov. 27, 1796. In 1825, MacEnery, who had just become the Roman Catholic chaplain at an abbey in Torquay, on the southern English coast in Devonshire, began excavating in Kent’s Cavern (also known as Kent’s Hole), a well-known cave lying along Tor Bay. Using a pick to break through the thick stalagmite crust on the floor of the cavern, he was surprised to find not only the bones of extinct animals such as mammoths and hyenas, but also flint tools that looked to be ancient human artifacts.

MacEnery initially believed he had found evidence that humans lived on earth at the same time as mammoths and cave bears, which would mean that humans were not recent additions to the earth, but were truly ancient. At the time, hardly anyone believed in human antiquity. MacEnery took the precaution of consulting William Buckland, the foremost authority on caves, and Buckland declared emphatically that the tools and the extinct animals could not possibly be contemporary. MacEnery returned to the cave twice more, but his enthusiasm for human antiquity seems to have waned, and he apparently came to believe that Buckland was right.

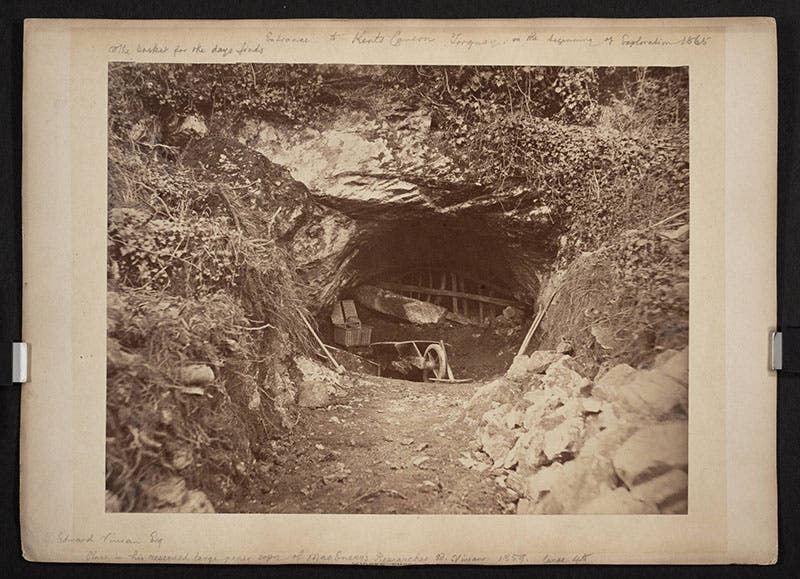

Photograph of Kent’s Cavern entrance (Linda Hall Library)

After his last visit to the cavern in 1829, MacEnery prepared a manuscript about his discoveries, but he never published it, and when he died prematurely in 1841, his collections and papers were sold at auction and dispersed. Not until 1859 was his manuscript printed, in an abbreviated form, as Cavern researches: or, Discoveries of organic remains, and of British and Roman reliques, in the caves of Kent’s Hole, edited by Edward Vivian. Ironically, this was the very year that human antiquity was first accepted by archaeologists and geologists, based on discoveries in nearby Brixham cave. We displayed MacEnery’s handsome posthumous book in our 2012 exhibition, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity.

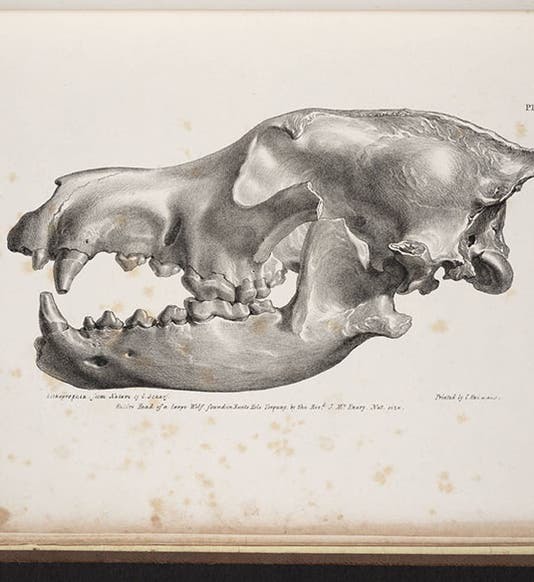

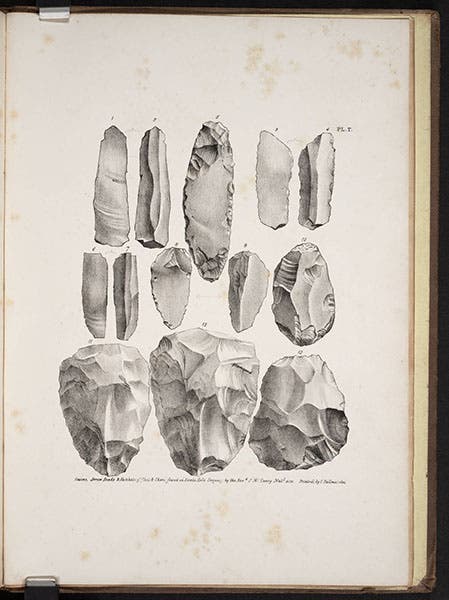

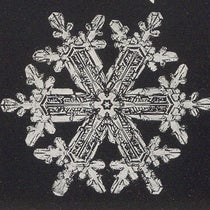

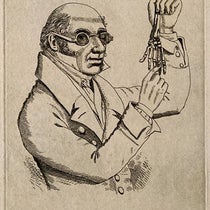

Our copy of Cavern researches just happens to have once been the personal copy of the editor, Edward Vivian, with his penciled signature on the front endpaper and additional annotations, and with some inserted material, including a large photograph of Kent's Cavern (third Image). Two images from MacEnery’s book show a cave bear skull (first image) and a collection of stone tools (second image) from Kent’s Cavern.

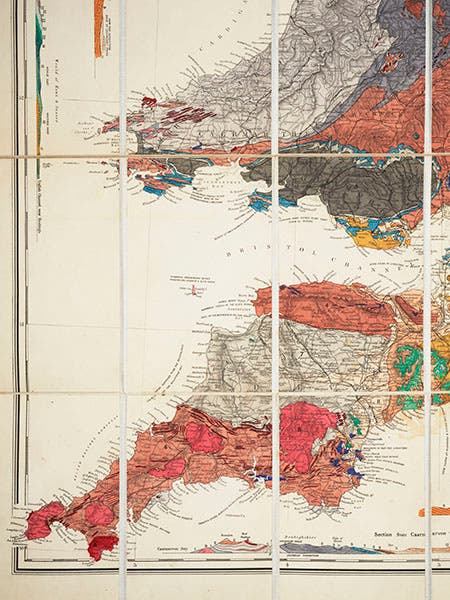

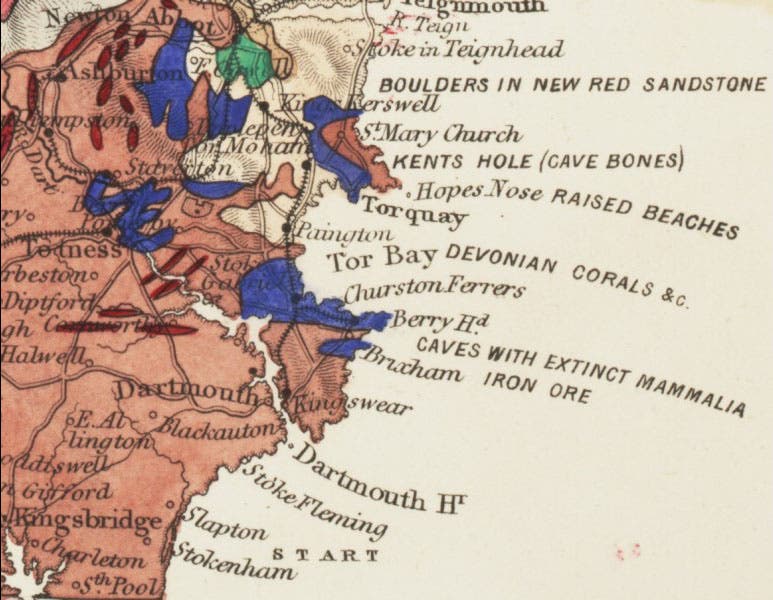

We also include a detail of a contemporary geological map of southwestern England (fourth image) and an ultra-detail from that map, showing Tor Bay and Kent’s Hole, at the top of the bay (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.