Scientist of the Day - John Lloyd Stephens

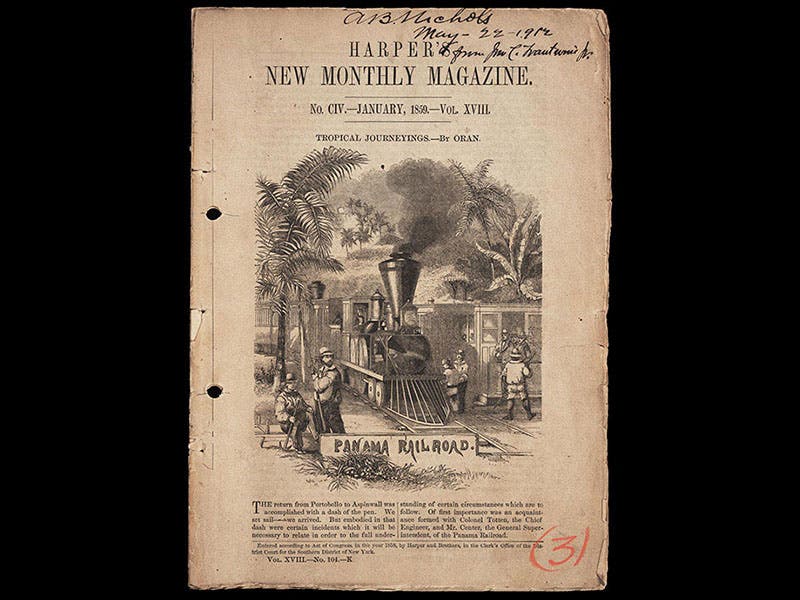

John Lloyd Stephens, an American explorer and railway builder, was born Nov. 28, 1805. In 1839, Stephens went to Central America with artist and architect Frederick Catherwood to investigate rumors of ancient ruins. They went first to Copán, then to Palenque and three dozen more sites. They found ruins in abundance. Catherwood recorded the glyphs and carvings as accurately as if he had a camera. What makes the pair special in the annals of Mesoamerican archaeology is that they recognized almost immediately that the ruins must have been built by native Mesoamericans and not by European invaders, as everyone else seemed to assume. They also realized that since the living Mayas had no such abilities or inclinations, the builders must have lived long ago, and the history of Central America must go back much further than anyone imagined. They published Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan in 1841, which was (and still is) a best-selling travel narrative. Then they returned to the Yucatan in 1842, visiting such sites as Chichén Itzá, and published a second narrative, Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, 1843. Both books are illustrated with the beautiful drawings of Catherwood (second image). We do not have either work in our Library, but the Spencer Reference Library at the nearby Nelson-Atkins Museum has a 1st edition of Travels in Yucatan, and an early edition of Travel in Central America.

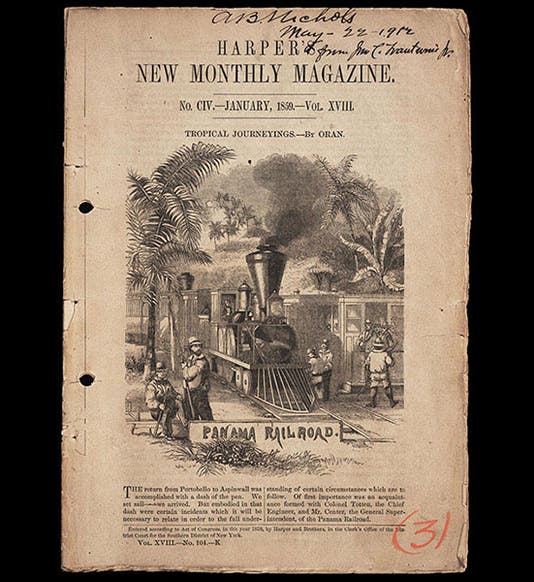

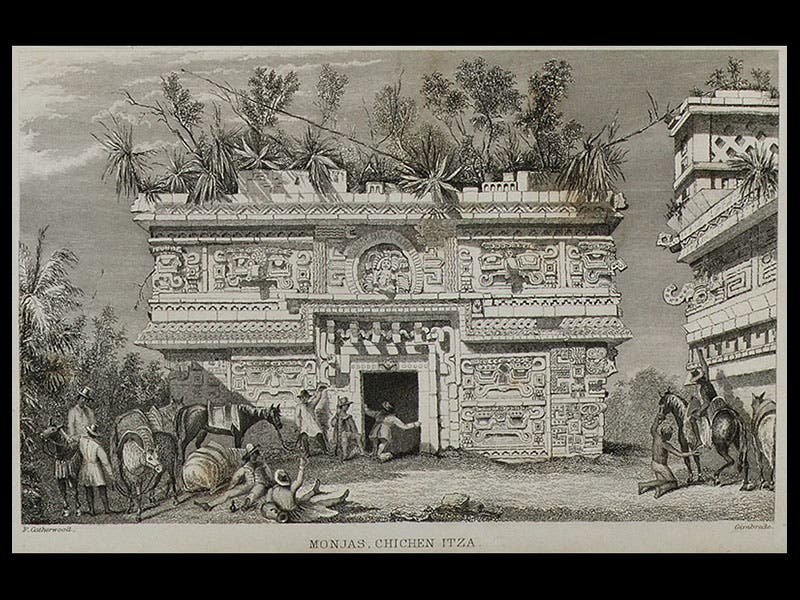

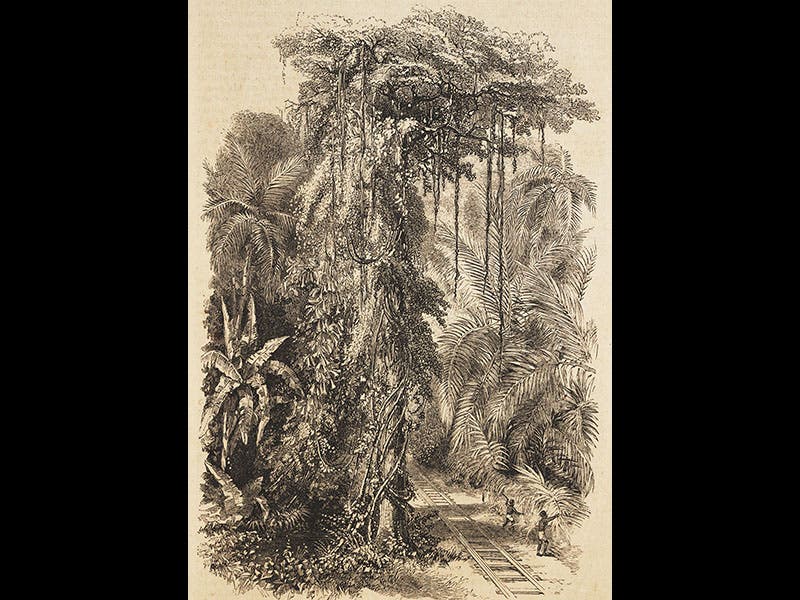

For all his fame as the one of the pioneers of Maya studies, Stephens is equally acclaimed as the father of the first Panama Railroad. There were several desultory attempts to build a railway across the Isthmus of Panama in the 1840s, so that prospective settlers of California would not have to make the long journey overland or the even longer voyage around the Horn. But the need and desirability for the railroad accelerated ten-fold with the discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill in 1848. Stephens surveyed the route for the railroad, found a pass across the mountains at Culebra, negotiated a 99 year lease with Columbia, and even arranged the $600,000 payment to secure the lease--all in six months in 1848. When the U.S. government declined to back the railway financially, Stephens and his two fellow entrepreneurs went ahead anyway. Stephens supervised the laying of every foot of track, for the rest of his short life, from his headquarters midway across the Isthmus. The Panama Railroad was completed in 1855. A copy of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine from 1859, in the collection of later Panama Canal engineer A.B. Nichols, shows the railroad in operation. The Nichols collection of Panama Canal materials is held at the Library and provided much of the display material for our 2014 centennial exhibition, The Land Divided, the World United: Building the Panama Canal.

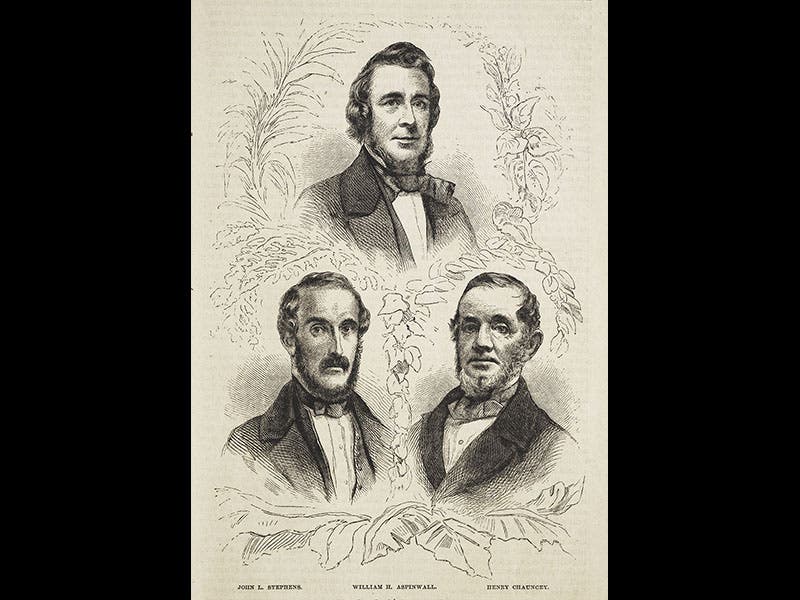

Stephens was very ill during most of the railroad work, suffering from what was then called Chagres fever, a blanket term that covered malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and a host of other tropical diseases, and in Stephens’ case was made worse by complications from a fall from a mule that often left him unable to walk. He died in 1852 and did not live to see the completion of the railway. Local tradition had it that he expired under a tree along the line of the railroad, a tree that he had conserved, even though it lay right next to the track. In fact, he died back at his home in New York, but the tree occupied a special place in Panama lore and was carefully preserved during all later developments, right up through the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914. Two photographs of Stephens’ Tree, as it came to be called, were displayed in our exhibition; we show one of them above (third image). We also displayed a page showing portraits of Stephens and his two financial backers. We reproduce those portraits here as well (fourth image); Stephens is at lower left.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.