Scientist of the Day - John Kendrew

John Cowdery Kendrew, an English biochemist, was born Mar. 24, 1917, in Oxford. He studied chemistry at Cambridge before war broke out in 1939, and spent much of the war working on radar, which gave him an exposure to technology that was unusual for life scientists. After 1945, he switched to biochemistry and began working with Max Perutz at what became the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology at Cambridge, looking for a way to uncover the structure of large organic molecules like hemoglobin. The only way to do this in the 1950s was with x-ray crystallography, bouncing x-rays off molecules and recording the various reflections and refractions, as Rosalind Franklin had just done with the DNA molecule in 1952. Perutz was tackling the structure of hemoglobin, an enormous molecule. Kendrew chose a protein, myoglobin, just 1/4 the size of hemoglobin. And he became an x-ray crystallographer.

The trouble with trying to map large molecules is that there are tens of thousands of data points to be analyzed. Kendrew was one of the first crystallographers to make use of the new stored-program computers just becoming available in the 1950s, while others were still relying on punched-card calculators to handle their data. Kendrew also set himself apart with his willingness to build models.

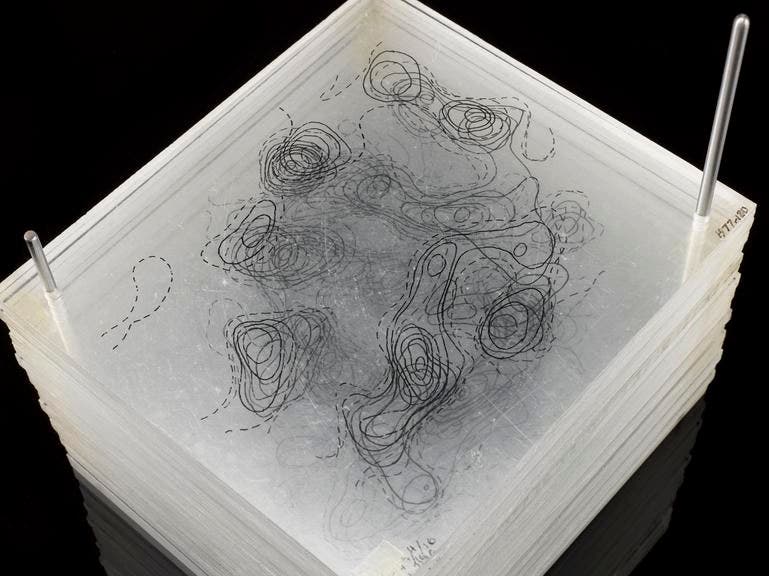

Models were not in common use in biochemistry in 1955. James Watson and Francis Crick had built a famous model of the DNA double helix in 1953, but that was more of a demonstration model, to show their hypothesis worked, than a discovery model. Kendrew used models to uncover myoglobin's structure in the first place. He made his first model, the so-called "sausage model," in 1957, using low resolution scans (third image). He was aided by electron density scans that he drew on sheets of transparent acrylic plastic and then stacked up to reveal the "sausage" within (fourth image).

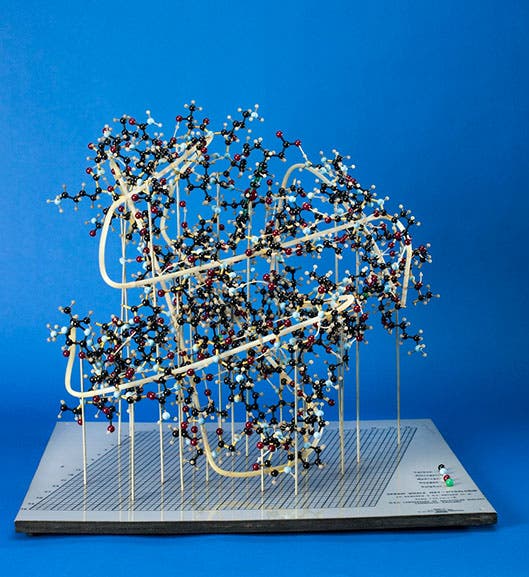

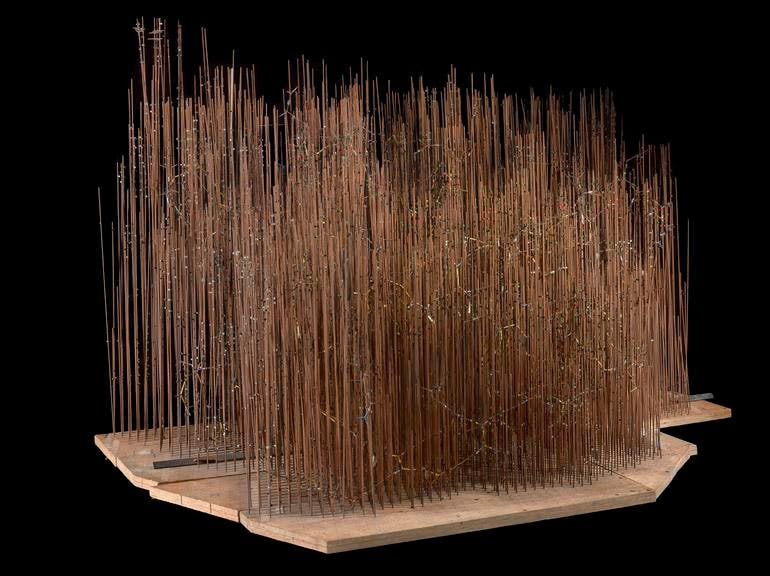

With higher resolution scans, Kendrew used more complicated kinds of models, especially one called the "forest of rods," where thousands of rods were set into a base plate and regions of higher density were indicated by attaching colored markers along the rods, like creating a three-dimensional graph paper (fifth image). The models helped Kendrew unravel the intricate structure of myoglobin, which he announced in 1959. It was quickly recognized that these models were themselves historic, and they have been preserved (unlike Watson and Crick’s original DNA model, of which only a few pieces survived, so it had to be reconstructed). The BBC even filmed a special program, Shapes of Life, in 1960, for which all these various models were gathered together in one room, demonstrating tactilely the value of model-building.

Kendrew was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962 for the discovery of the structure of myoglobin, sharing it with Perutz, who discovered the structure of hemoglobin. The group photo of the awardees for 1962 (sixth image) shows quite an array of molecular biology talent, since Watson and Crick also received the Prize for their work on DNA, along with Maurice Wilkins. I have always felt sorry for John Steinbeck, who had to dine with these men and explain that Of Mice and Men had nothing to do with a biological laboratory.

Group photograph of the 1962 Nobel Prize winners in Stockholm, with John Kendrew at far right, next to James Watson. The three on the left are Maurice Wilkins, Max Perutz, and Francis Crick. Novelist John Steinbeck, third from right, looks quite uncomfortable in the company of men who speak an entirely different language (www.achievement.org)

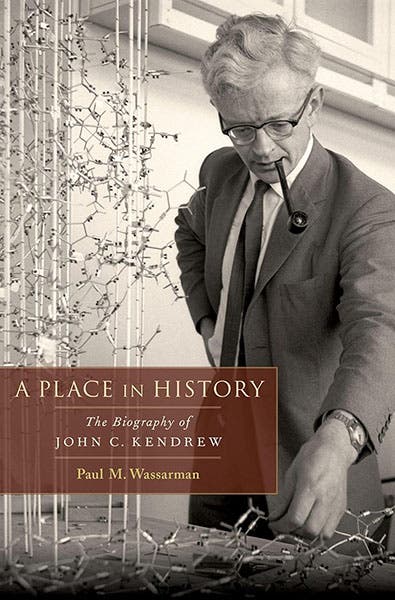

There is a recent biography of Kendrew, A Place in History: A Biography of John C. Kendrew, by Paul M. Wassarman, Oxford Univ. Pr., 2020. I have not read it, because our library has not yet bought it, for some reason. I show the dust jacket (second image), because it has a better portrait of Kendrew than you can find online, and because it captures him as a model- builder. I have read Designs for Life: Molecular Biology after World War II, by Soraya de Chadsrevian (Cambridge, 2002), in which Kendrew plays a major role.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.