Scientist of the Day - John Harris

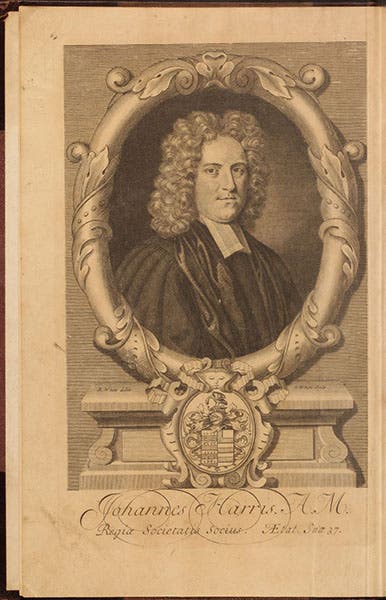

John Harris, an English mathematician and encyclopedist, died Sep 7, 1719, at the age of about 52. Harris is best known for his Lexicon Technicum, the first alphabetical scientific encyclopedia published in English, which initially appeared in a large quarto volume in 1704. Six years later he published a second volume, which also went from A to Z, but, interestingly, did not repeat anything in the first volume.

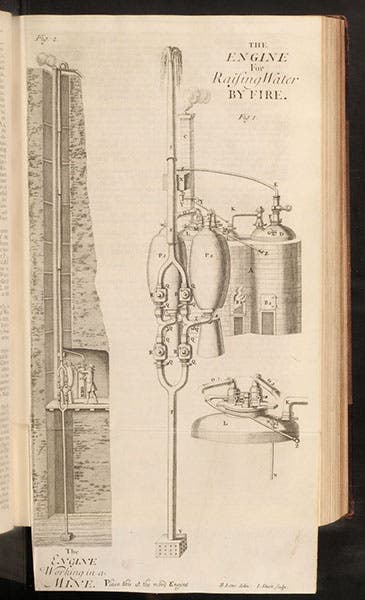

Harris claimed that his encyclopedia was a new kind of reference work, designed not to be read piecemeal, but in large chunks, like a real book, since he took great pains to make the work a coherent whole. Out of curiosity, I tried this, opening volume 1 at random and reading a number of articles in a row. The entries are usually short, sometimes only a line or two, and I learned great deal about heraldry, and the bones of the human body (each one is listed and defined, in its proper alphabetical place, as far as I could tell), and occasionally I ran into a really interesting article, such as the one on “Engine”, where Harris discussed Thomas Savery's brand new steam engine, illustrating it with a large engraved plate (third image). But I must confess, the coherence escaped me, especially since there were no cross references of any kind.

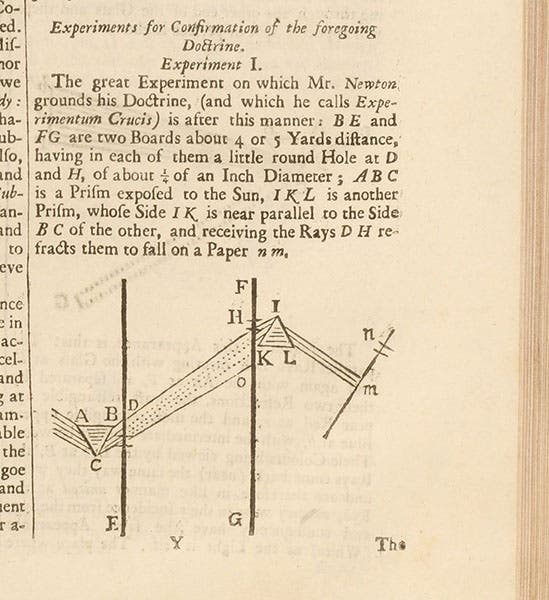

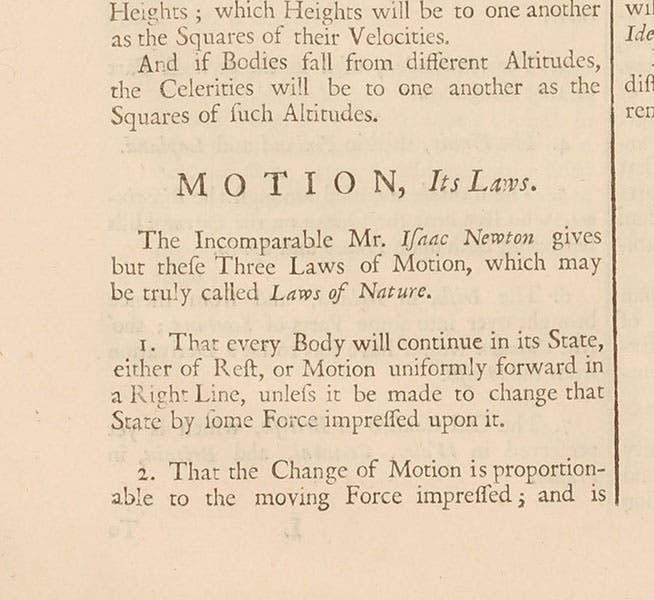

Nevertheless, I was impressed; Harris was as up on Isaac Newton as anyone at the time, and accurate references to Newton are liberally sprinkled throughout the work. We show here two passages, one where Harris accurately describes Newton’s experimentum crucis, where Newton broke light down into its constituent colors with a prism, and then showed that it was impossible to break the colors down further with an additional prism (fourth image), and another where he presents Newton’s three laws of motion, translated from Newton’s Principia (1687) (the presentation continues in the next column, not shown here) (fifth image).

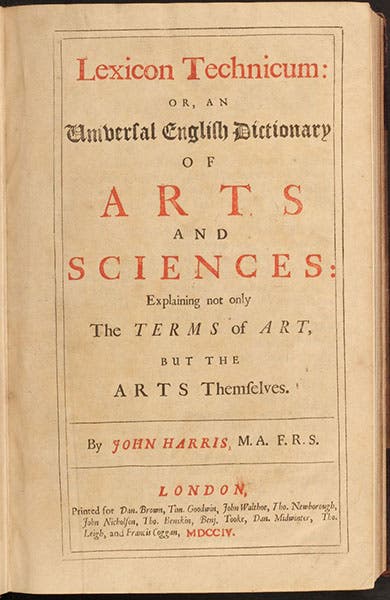

We also learn something important about the Lexicon from its full title: Lexicon Technicum: or, An Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences; Explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves. Harris’s goal was not just to explain the nomenclature of physics, but physics itself, making it far more than just a dictionary. Harris proudly says in the preface, that he compiled his entries, not from other reference works, but from the original sources, to ensure its reliability.

Aside from simple diagrams, there are not many real illustrations in volume 1 of the Lexicon; in addition to Savery’s steam engine (which he copied right out of Savery’s The Miner’s Friend, which had been published just two years before, in 1702), there are two engravings of the air pumps of Robert Boyle and Francis Hauksbee, and one depicting a microscope by John Marshall, and that’s it. Everything else is text – lots of text.

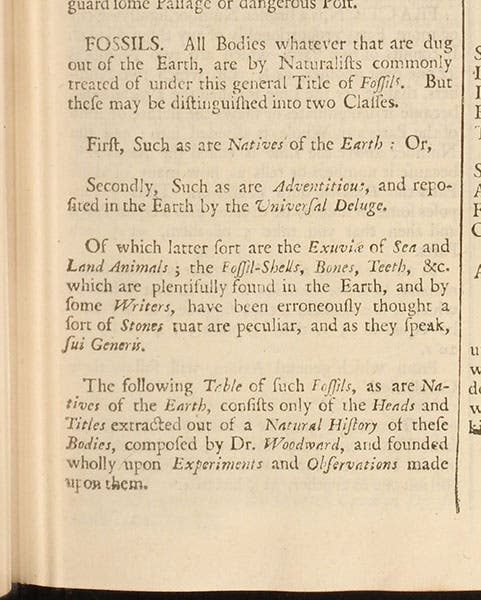

Another area of interest for Harris was fossils. He was a good friend of John Woodward, who had written A Natural History of the Earth (1695), in which he argued that fossils were the remains of living organisms that had been deposited in the Earth’s crust by a universal deluge, i.e., the flood of Noah. You can see Harris’s adherence to Woodward in his entry on “Fossils” (sixth image). Some years earlier, Woodward’s book had been attacked by an anonymous critic, and Harris had leapt to Woodward’s defense with his own treatise, Remarks On some Late Papers, Relating to the Universal Deluge: And to the Natural History of the Earth (1697), which we also have in our collections (seventh image). We displayed both books in our exhibition, Theories of the Earth (1984), the very first exhibition I curated for the Library.

The first volume of Harris’s Lexicon was reissued in 1708, and most libraries that have the first edition have this second printing paired with the 1710 first printing of volume 2. We are fortunate to have the original 1704 printing of the first volume. We also have a fourth edition of the Lexicon, published in 1725. Harris's Lexicon directly inspired Ephraim Chambers Cyclopedia (1728, which did add cross-references), and Chambers in turn helped shape the later Encyclopedié (1751-72) and the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768-71).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.