Scientist of the Day - John Frémont

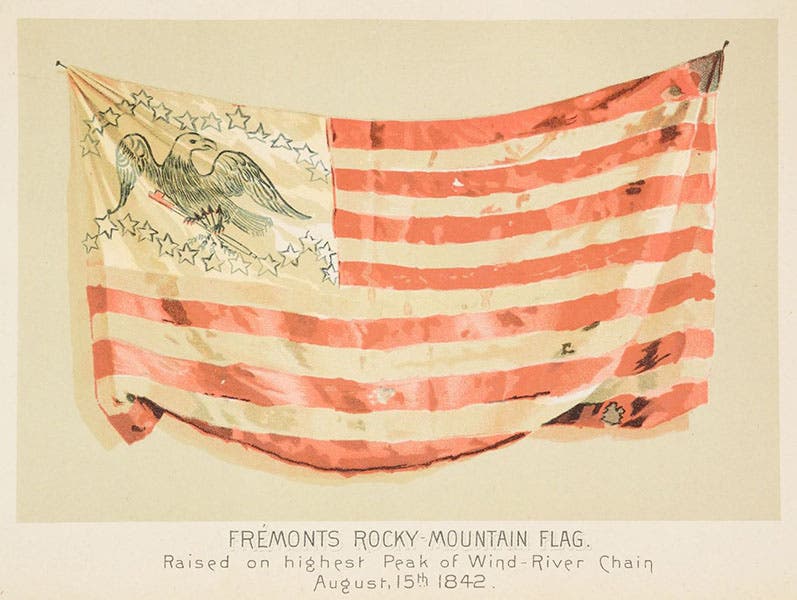

John Frémont, an explorer of the American West, died July 13, 1890, at the age of 77. Nicknamed “The Pathfinder," Frémont was probably the most celebrated of all the Western explorers, even though he did not really deserve that fame. After participating in several trips out west, he led three government expeditions to the Rockies in the 1840s. The first expedition, which included Kit Carson as guide, left St. Louis in 1842, with a commission to survey the Oregon Trail. When they got to the Wind River Range in Wyoming, Fremont climbed a mountain, which he called the tallest in the Rockies, and planted a homemade American flag. The mountain was later named Fremont Peak, and is in fact well down on the list of tall mountains, but no one cared back East. The Pathfinder legend had begun.

Fremont was greatly aided in his quest for fame by his wife, Jessie, who served as his publicist, and by his father-in-law, Thomas Benton, U.S. senator from Missouri. Marrying into the Benton family had led to the commission for his first expedition, and he soon received a second, to return to the Oregon Trail and make an accurate cartographic survey. He took along Charles Preuss, an experienced topographical engineer who had been on the first Frémont expedition, and their maps, which gave the locations of water supplies, possible campsites, and sources for wood, were the finest yet obtained for any western region. Frémont made it all the way out to the Columbia River and Fort Vancouver. After his return, Frémont wrote, with the help of his wife Jessie, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains (1845), which Congress published in tens of thousands of copies, and which guided many a settler through the West, including Brigham Young.

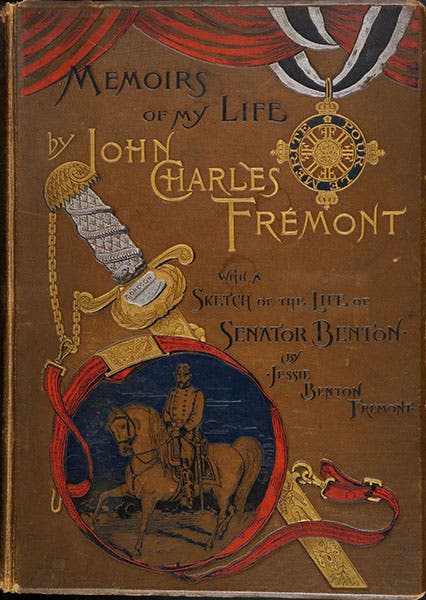

Frémont would lead five expeditions to the West in the 1840s and 1850s, three for the government. Historians regard him as barely competent as an explorer and leader – Preuss thought he was totally incompetent – yet he managed to get commission after commission. Such is the way of political appointments, then and now. His narratives, however, were very well written, mostly because of Jessie, and they are filled with information and enticing illustrations. We have the narratives of the first two expeditions (plus an English edition of the second one), but we take our images today from Frémont’s Memoirs (1887), written mostly by Jessie and recounting all of John's Western exploits. It was a lavish publication, written to make money, although it did not, when income had dried up and John was in deteriorating health. The embossed and colored cover is as decorative as a book cover can get (fifth image), and there are many, many plates, in all sorts of formats – lithographs, line engravings, zinc etchings, even photo-lithographs and photo-engravings. An unexpected treat is a full-page color plate of the hand-made American flag that Frémont waved from atop his soon-to-be eponymous mountain (seventh image).

Four years ago, we wrote a post on Raymond Ostrander Smith, one of our country's first and most gifted postal stamp designers, who happened to be fascinated by exploration and technology. His series of nine commemorative stamps, called the Trans-Mississippi Issue, was released in 1898, and the 5-cent stamp of that issue commemorated the planting of the American flag on Mt. Fremont. You can see it as the second image in our post on Smith.

In 2004, the Library mounted an exhibition, Science Goes West, documenting the scientific exploration of the West in the 19th century, which was curated by Bruce Bradley and myself, and it has always been one of my favorite exhibitions, even though we did not have the resources to print a catalog or even put one online. In that exhibition, we displayed five Frémont items, the four mentioned above, plus, a report on a map of the Upper Mississippi, made by Joseph Nicollet, assisted by a young Frémont. It would be nice to remount that exhibition someday with a proper catalog. I don't think any other rare book Library has ever done anything like it, before or since.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.