Scientist of the Day - John Chapman

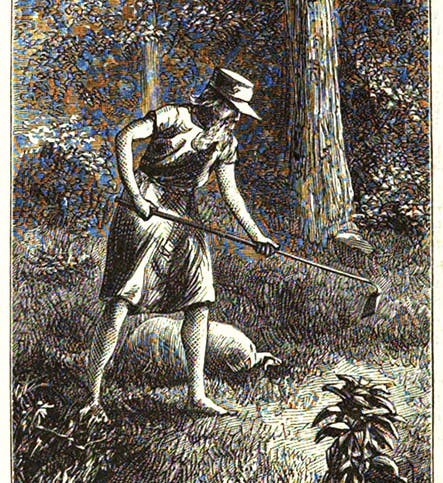

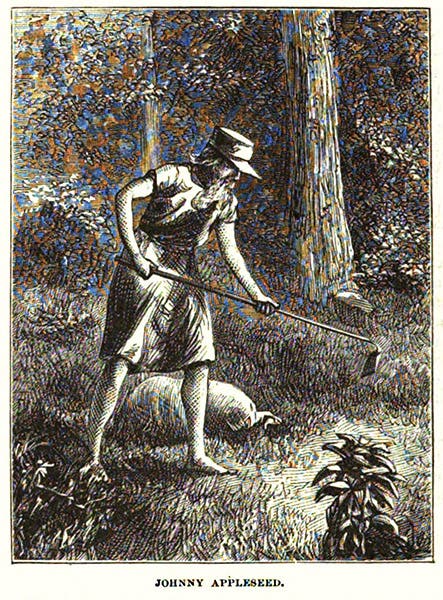

Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman), woodcut in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 43, no. 258, Nov. 1871 (Harvard University copy on hathitrust.org)

John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed, nurseryman extraordinaire, was born Sep. 26, 1774, in Massachusetts. It is hard to sort through the legend of Johnny Appleseed to find the real John Chapman, but several historians have recently managed to make credible attempts. Chapman was a real enough figure, an itinerant who moved west to Pennsylvania, then Ohio, and finally Indiana, acquiring plots of land here and there, where he would plant orchards of apple trees from seed, and sell the sprouts for a penny or two apiece, which is where he got the money to buy land. He lived simply, wore second-hand clothes, disdained shoes, and slept on the ground except in extreme weather, when he had no problem finding a floor by a hearth, since he was a well-loved figure among the settlers.

In addition to sowing apples, Chapman spread the Gospel as he went, as taught by a Christian sect known as Swedenborgians, or the New Church, which seems to have emphasized the oneness of humans with nature. I do not know much about the Swedenborgians, but I do know a little about Jainism, and Chapman sounds like a Jain to me, although a Christian version. He respected all forms of animal and plant life, refusing to kill anything, even insects. Most apple trees were the result of grafting onto a rootstock, but Chapman refused to cut and wound a tree, and so he grew his trees from seeds. It has however been pointed out, cynically perhaps, that grafting is difficult and time-consuming, whereas it is fairly easy to haul around a gunnysack filled with seeds, which could be acquired free at cider mills.

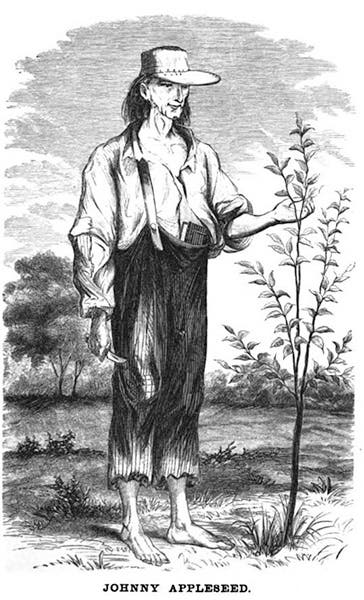

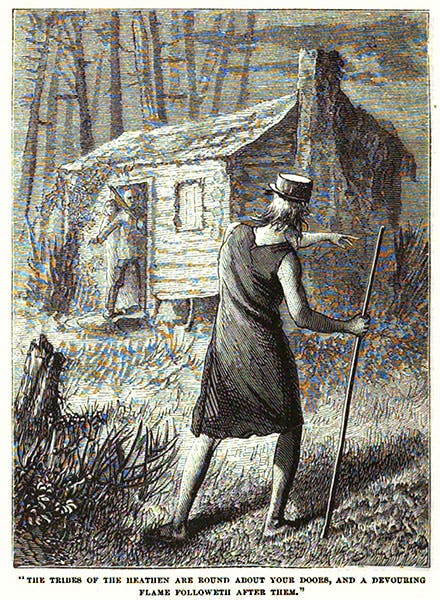

Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman), second woodcut in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 43, no. 258, Nov. 1871 (Harvard University copy on hathitrust.org)

The problem with growing apple trees from seed is that, if you plant the seeds from, say, a MacIntosh apple, you do not get a tree that bears MacIntosh apples. The seeds are unrelated to the apple the contains them. So the apples from Chapman’s trees were generally small and bitter. The fact that they were probably not too tasty may not have put a crimp in Chapman’s business, for the buyers of his two-penny sprigs were unlikely to know what kind of fruit they would bear until after Chapman had moved on. And they probably would not have cared, for the fact is that the reason people wanted apples was not to make America's favorite dessert, but rather to turn them into hard alcoholic cider. In hindsight, we know that Chapman’s habit of growing apples from seed was an ecological godsend, since he managed to leave behind an incredible variety of apple trees and thus inadvertently preserved most of the diversity inherent in the apple genome.

How Chapman morphed into the legendary Johnny Appleseed, who wore a pot for a hat and could communicate with animals, is not altogether clear. The mythical Appleseed probably blossomed from an article in Harper's New Monthly Magazine in 1871, 26 years after his death. The article plays up his simple life, his missionary ways, and his reverence for animals. Recent scholarship has shown that Chapman may have led a simple life, but he was far from simple-minded, being a fairly shrewd and eventually wealthy businessman, who had accumulated quite a bit of valuable acreage and capital by the time of his death.

Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman), third woodcut in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 43, no. 258, Nov. 1871 (Harvard University copy on hathitrust.org)

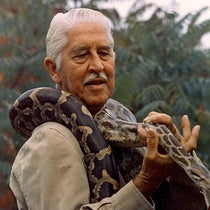

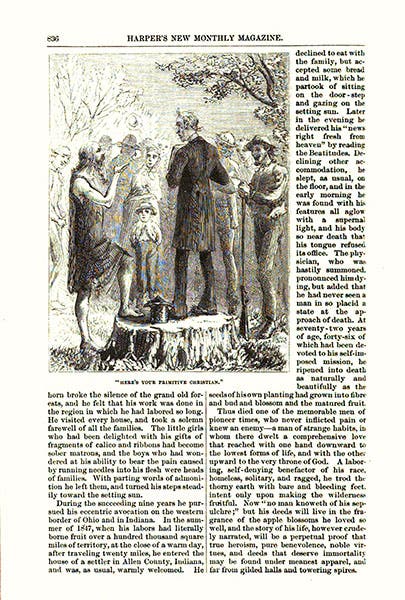

There are only two sets of near contemporary images of John Chapman, and both are posthumous. One is a single woodcut portrait that appeared in an 1862 history of Ashland County, Ohio, which I have no access to, but which is reproduced on Wikipedia, from which we borrow it (second image). An account of Chapman in this book is one of the sources for his tin-pot hat. The other visual record is a set of three woodcuts that were included in the Harper’s New Monthly article of 1871. For want of any other visual aids, I include all three here (first, third, and fourth images), from a copy at Harvard. The third of the Harper’s woodcuts illustrates a story of an itinerant preacher, railing against modern decadence, who cried out, “Show me a primitive Christian,” whereby Chapman stepped forward in response (fourth image).

Of course, if you prefer a pot-for-a-hat version of Chapman, you have your choice of dozens of covers from a variety of modern children’s editions of the Johnny Appleseed story. I cannot in good historical consciousness include one here, but I can provide you with a link, or two.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.