Scientist of the Day - John Bartram

John Bartram, a colonial American botanist, was born Mar. 23, 1699, in Pennsylvania. Bartram is commonly referred to as the first native-born American botanist, and this country's first horticulturalist as well. Linnaeus considered him the finest natural botanist in the world, whatever that means. HIs parents were Quakers from Derbyshire in England; they emigrated to Pennsylvania, after William Penn offered land to all comers, and set up a farm at what should have been called New Derby, but was instead named Darby, just a few miles west of Philadelphia. Young John had no formal higher education, although the Quakers were pretty good at establishing local schools, and he taught himself most of what he knew about plants, which was a lot. He established his own garden in 1728 at Kingsessing, on the Schuylkill River, where he spent the rest of his life raising plants that he had brought back from forays into countrysides near and far.

In 1733, Bartram swam into the ken of John Collinson, a Quaker merchant in London and an avid gardener himself. Collinson had been trying for years to find an American source for seeds and cuttings, without any luck, until someone at the Library Company of Philadelphia recommended Bartram. Collinson ordered some seeds, Bartram fulfilled the order promptly, and thus began 25 years of uninterrupted trans-Atlantic botanical exchange, with Collinson paying 5 guineas each for boxes of seeds and dried plants that Bartram would pack up himself and convey to trusted ship’s captains. Eventually, Collinson became the middleman for half-a-dozen English gardeners, buying specimens from Bartram and farming them out to his friends. It was a valuable arrangement for both men; it provided Bartram with a livelihood, and it made Collinson's garden, and such beneficiaries as the Chelsea Physic Garden, horticultural hotspots, with their displays of rhododendrons and Venus flytraps, provided by Bartram.

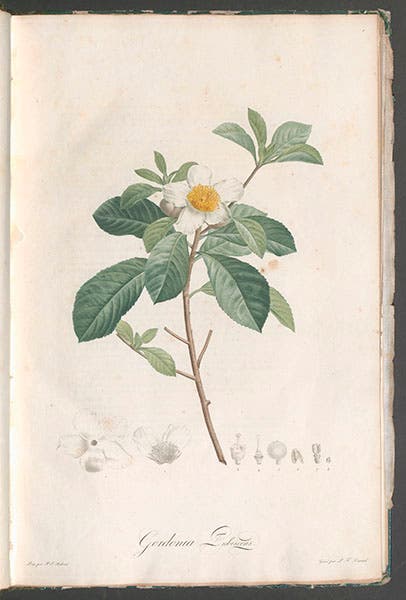

Bartram at first looked for new plants on local explorations, but he eventually cast a wider net, travelling through upstate New York, and then to the colonial southeast. It was while on a trip to Georgia in 1765 that he found a stand of flowering trees new to him; the tree was eventually named Franklinia alatamaha, after his good friend Benjamin Franklin, and Bartram brought back seeds from Georgia which he successfully sowed at Kingsessing. Franklinia turned out to be Bartram's greatest, or at least his most famous, discovery, as the tree disappeared from the wild, so that all modern specimens of Franklinia are descended from stock raised by Bartram in his garden. A Franklin tree was drawn by Bartram's son, William, and sent to John Fothergill, William’s Quaker patron in London; we showed that drawing in our post on Fothergill not long ago. A specimen that ended up in Josephine's garden at Malmaison in France was drawn by Pierre-Joseph Redouté and published in Étienne-Pierre Ventenat's Jardin de la Malmaison (1803-04), under the name Gordonia pubescens (fourth image). I had looked at this plate many times but was unaware until researching this essay that it actually depicts Franklinia alatamaha. We once had a Franklin tree on the grounds of our library, but it was not partial to our winters and moved on to tree heaven. We should try again – these days it might have better luck.

Bartram kept a Diary of a Journey through the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, about his journey to the southeast in 1765-66; it was eventually published in 1942, and frequently reprinted, although for some reason it is lacking from our collectons. Bartram was also an assiduous correspondent, especially to Collinson, and those letters have been edited and published, and we do have those in our collections, along with a large number of contemporary studies and biographies. Bartram is a very popular colonial American figure nowadays.

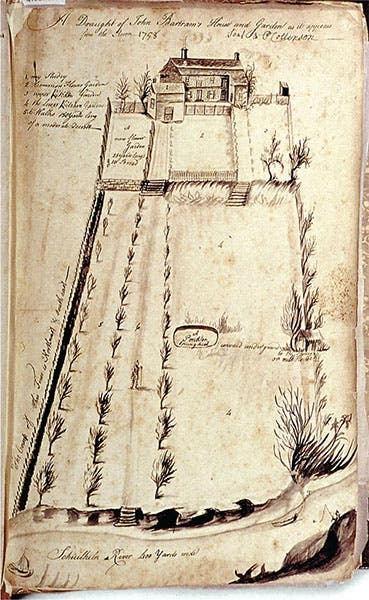

Bartram’s house and garden have been preserved and restored and are open to the public as Bartram’s Garden, in southwest Philadelphia; it is also a National Historic Landmark (first image). Every August, when Franklinia blooms, there is usually a special tour, with images posted on their website; here is an example from a few years back.

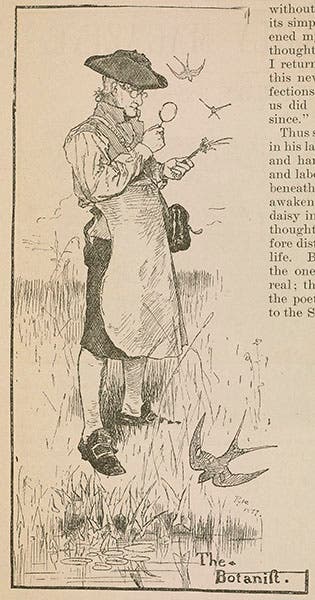

There is no surviving contemporary portrait of John Bartram. The one that everyone uses (including us) is a drawing made by the noted 19th-century illustrator Howard Pyle, and published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Feb. 1880. We show you a print from the Smithsonian Institution Libraries (second image). There is a contemporary map of Bartram’s garden, drawn by his son William in 1758 (third image). It is in the archives of Bartram’s Garden.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.