Scientist of the Day - John Auldjo

John Auldjo, a Canadian/English traveler and sketch artist, was born July 26, 1805. Although raised in Montreal, he attended Trinity College, Cambridge, and never returned home. He began a Grand Tour in 1827, climbed Mont Blanc, then visited Naples, where he became part of a social and diplomatic set there that included such visitors as Walter Scott and Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He remained in or near Naples the rest of his life.

In 1831, Auldjo visited Mt Vesuvius, which was then in a moderately active state. He took his sketchpad along, and soon thereafter wrote an illustrated account of his adventures. The account is interesting but not especially novel or illuminating. The illustration, however, are superb – in our opinion, the most attractive and well-laid-out, close-at-hand images of Vesuvius ever published.

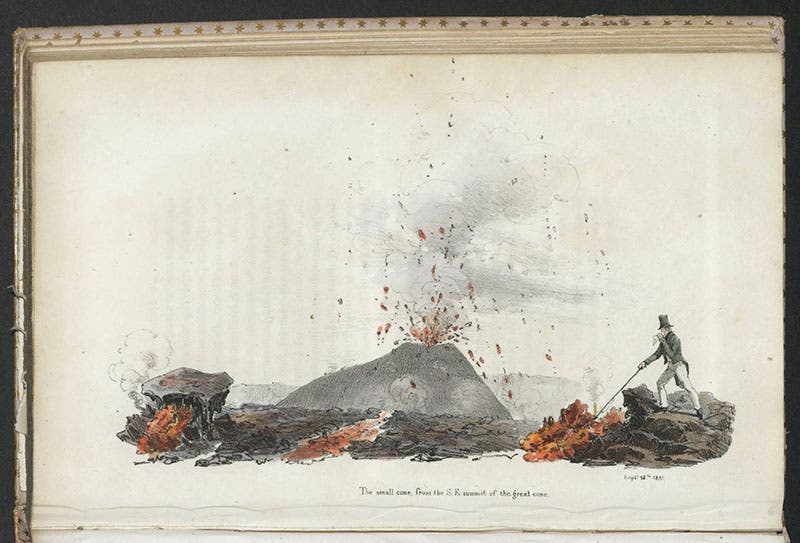

Our second image is a plate that folds out multiple times from the thin octavo narrative. It shows the Vesuvius crater, up to which Auldjo and his party had hiked on Sep 18, 1831, with a small cone spewing lava in the background, and members of the party hiking or standing about. Auldjo himself is in the center, in his white pants and Panama-style hat. We show this center scene in a detail for our first image. Auldjo did the sketches from which all the prints were made. The sketches were printed as lithographs, to which color (mostly red, orange, yellow, and gray) was then added. Lithography for book illustration was still a bit of a novelty in 1832, especially in Italy, where the book was printed.

Another lithograph, this one quite a bit smaller, shows another small lava cone in the Vesuvius crater, with Auldjo again, holding a handkerchief over his nose to thwart the fumes, probing at the lava with his hiking staff (third image).

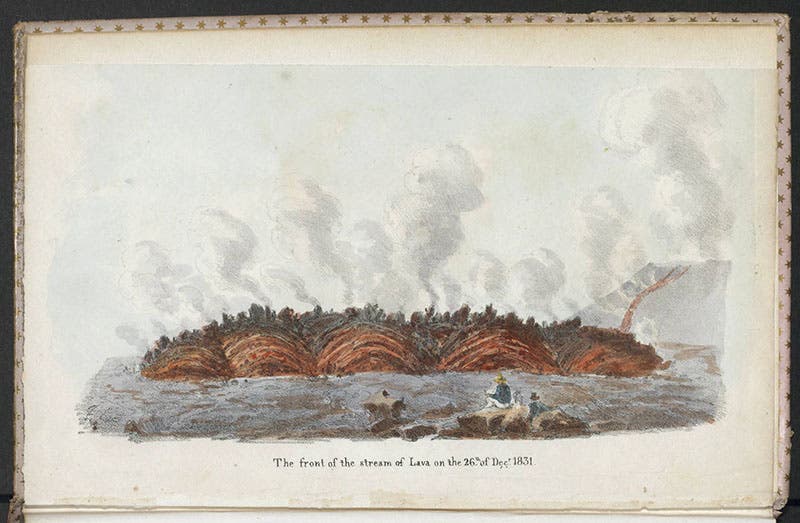

A third lithograph, made on a different occasion some months later, shows a lava flow coming directly at the viewer (fourth image). The man in white trousers is sitting in the foreground, drawing on his sketchpad. The same individual is depicting drawing in several other lithographs, which is why we know it is Auldjo, since he did all the sketches.

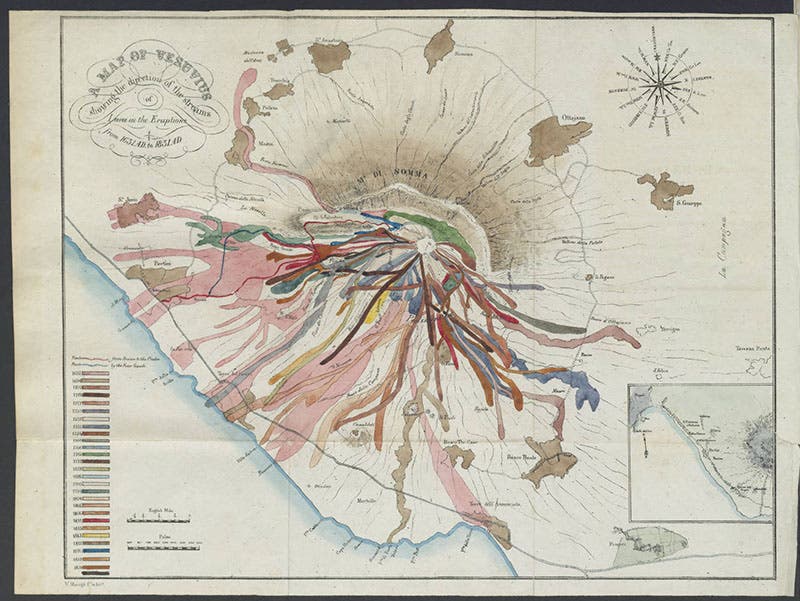

There is also a large folding map in the book, showing all the historic lava flows since 1631 in different colors, with a key, not legible here, at bottom left. There are 27 colors in the key and on the map, all applied by hand (fifth image).

Our final lithograph is a different kind of illustration, a distant view of Vesuvius at night, erupting dramatically (sixth image). The only added colors are red and yellow, but they are quite effective, especially in the reflection in the water.

The last forty years of Auldjo’s life is a bit of a mystery, although we know he had some diplomatic duties in Geneva late in life. It is sometimes said that he died and was buried in Geneva. He may have died there, but he was most definitely buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, Kensington and Chelsea, Greater London. The only portrait we could find is a carte-de-visite, made, we would guess, in the 1860s (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.