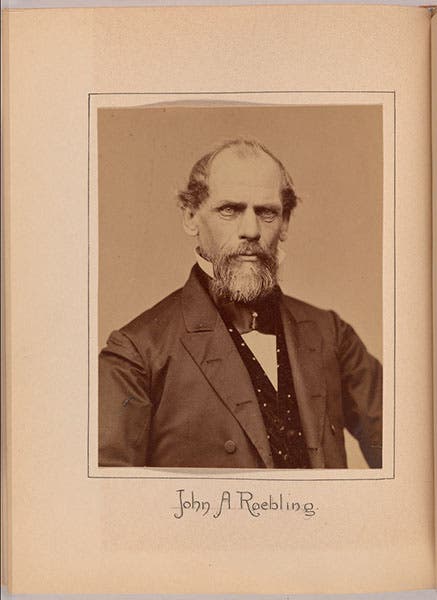

Scientist of the Day - John A. Roebling

John Augustus Roebling, a German/American civil engineer, died July 22, 1869, at the age of 63. Roebling came to the United States from Prussia in 1831, to further his employment prospects, and also to set up a Utopian community for other German émigrés. He settled in western Pennsylvania, and although the utopian plans for Saxonburg went the way of most utopias, Roebling found a niche making wire rope for canal tow cables, and then for small bridges. He became a staunch advocate for building suspension bridges utilizing wire cables, which before long he was manufacturing at his own wire-rope plant in Trenton, New Jersey. Suspension bridges were viewed with disdain by most American bridge engineers (such as there were), and even in Great Britain, where Thomas Telford pioneered the long-span suspension bridge, they were now building tubular bridges instead of suspension bridges, such as the Britannia Bridge over the Menai Straits, designed by Robert Stephenson and built by Edwin Clark.

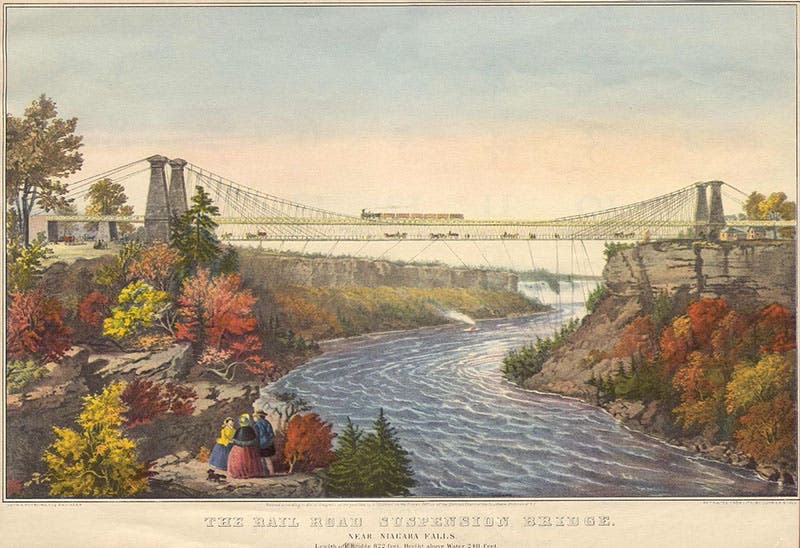

Roebling insisted that suspension bridges utilizing wire cables (Telford’s bridges used forged iron or steel links) were inherently stronger, safer, and cheaper than tubular bridges. He managed to get contracts for suspension aqueducts for canals, and for some smaller suspension bridges. He lost out to Charles Ellet, Jr., in his bid to span the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia, and then to Ellet again in a bid to span the Niagara River with a railroad bridge, just downstream from the falls. But when Ellet withdrew from the Niagara project, Roebling stepped in, beginning in 1851, and by 1855, he had finished a beautiful suspension bridge that was the talk of the engineering world (third image). Many engineers had claimed that a fully loaded train was much too heavy for a suspension bridge, and Roebling proved them wrong.

Roebling was soon highly sought after as a bridge builder. He won the contract to build a suspension bridge across the Ohio River, between Covington, Kentucky, and Cincinnati, in 1856. There was little support for such a bridge in the financial community in Cincinnati, so the project was beset with money problems, and progress was slow. Meanwhile, in 1857, sponsors in Pittsburgh asked Roebling to span the Allegheny River, and they had plenty of funds, so work proceeded rapidly. The Allegheny River suspension bridge opened in 1860. Roebling was not an architect, so the bridge looks a bit over-ornamented in hindsight. But structurally, it was perfectly sound. Scientific American ran a story on it ten years later, with a large wood engraving of the bridge (fourth image). Roebling’s bridge was more than adequate for 1860, but within 30 years, it could no longer meet carrying-capacity requirements, and it was replaced (and later, replaced again). So if you go to Pittsburgh and cross the 6th Street bridge, you will be travelling on the latest installment of the original Allegheny River bridge.

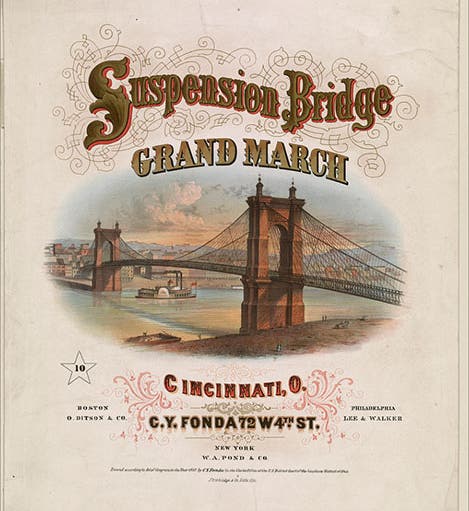

The Cincinnati bridge project, which wasn’t moving ahead very quickly, came to a complete standstill with the Civil War. But in 1864, work resumed, and the bridge was completed and finally opened on Dec. 1, 1866. It was, for a while, the longest suspension bridge in the world, with the central span extending over 1050 feet. And best of all, the bridge is still there, to be admired and driven or walked across. Originally referred to as the Covington-Cincinnati Bridge, it was renamed the John A. Roebling Bridge in 1983. It is a National Historical Civil Engineering Landmark. We show the cover of some sheet music for a march written for the opening ceremony in 1867, with a colored engraving of the bridge (first image), and a modern photograph of the bridge, still wearing its bicentennial-blue coat of paint (fifth image).

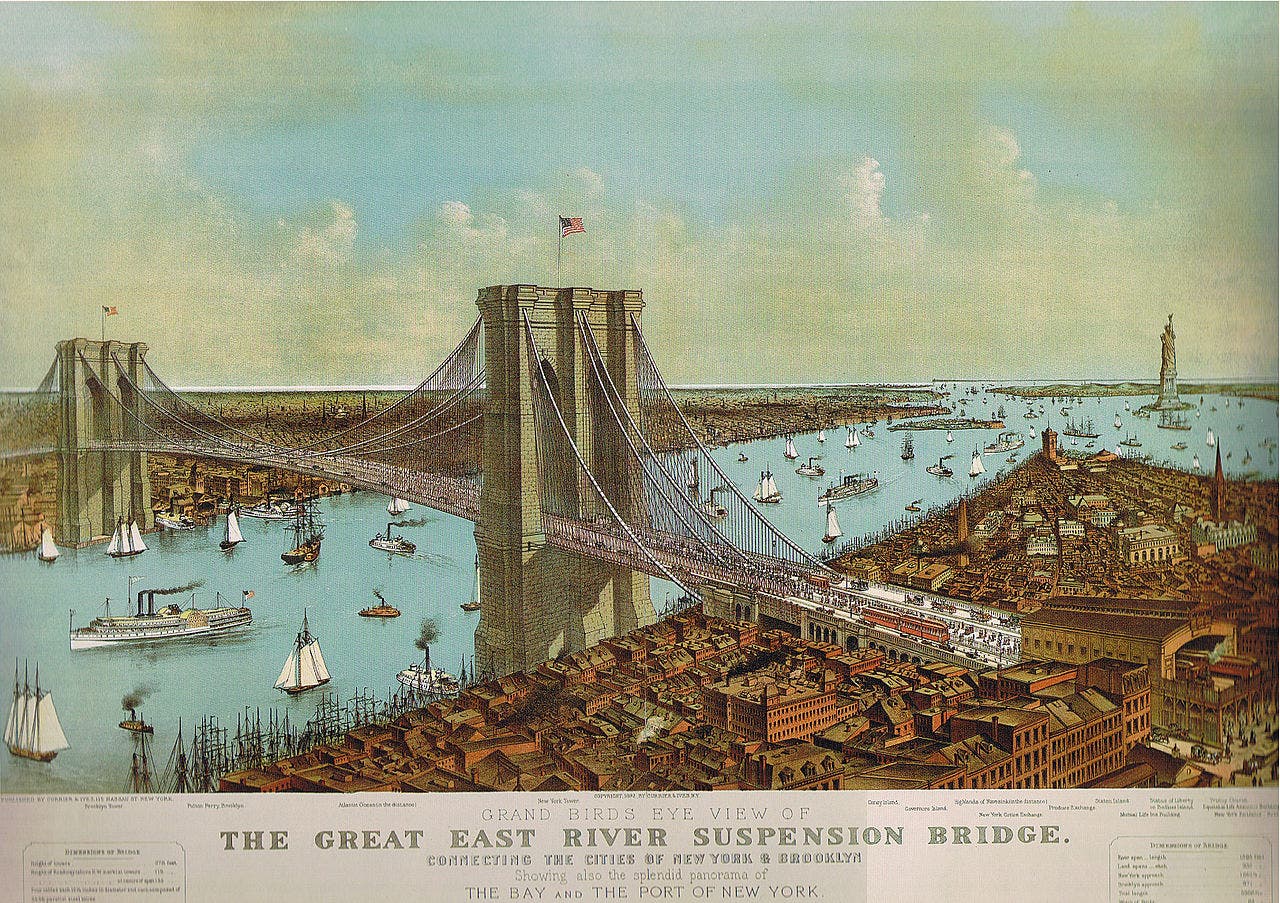

Roebling’s most famous bridge is the one that spans the East River between Brooklyn and Manhattan, now referred to as the Brooklyn Bridge. This is probably his most successful design, with its massive Gothic stone towers, lack of ornament, and those long, beautiful cables, which were strung on site. Construction was begun in 1869, and the Bridge would not be completed until 1883, opening to the public on May 24 of that year.

Roebling had to fight the ferryboat interests’ tooth-and-nail to get his project approved, and it is thus somewhat ironic that one day in the summer of 1869, while standing on a pier and surveying the river he was planning to span, his foot was crushed by an errant ferry. His toes were amputated, but tetanus set in, and he died, in the most agonizing way, three weeks later. Bridge construction was taken over by his son, Washington Roebling, who had trained with his father, and even though Washington was nearly incapacitated by caisson disease in 1872, he managed to bring the project to completion, greatly assisted by his wife, Emily. We have not yet written a post on Washington, but we have published one on Emily, where you can learn a little more about the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. It became at once an icon of Americana, and it remains so today (sixth image).

Roebling was buried in Mercer Cemetery in Trenton, and then his body was removed and reburied in Riverside Cemetery in Trenton, for reasons unknown to me. But that means he is one of the few people to have two entries on findagrave.com. The entry for Mercer Cemetery interestingly shows an empty plot of grass, where his grave used to be. We show instead a photo of the Riverside Cemetery plot, with its monument and family headstones (seventh image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.