Scientist of the Day - Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith and printer, died in Mainz on Feb. 3, 1468, at an age of 70 or less. He was also born in Mainz, although we don't know the date, or even the year, although it is often put at 1400, a convenient round number. Although Gutenberg is almost universally acknowledged as the father of printing with moveable type and the printing press, we know surprisingly little about the man and the path he took in developing his method of printing. If it weren't for the fact that Gutenberg was prone to being sued by partners and lenders, and that the German courts have always been very good at keeping records, we would know absolutely nothing. But it is generally agreed that by 1452, when Gutenberg began printing the famous 42 line Bible, Gutenberg had pieced together: 1) a method of casting type, using individual, flexible, and reusable molds that produced type of a uniform height, which also involved: 2), perfecting an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony that could be easily cast but that was hard enough to resist wear; 3) a technique for quickly assembling type into larger units, called formes, for printing; 4) a press capable of exerting great pressure but which, even though driven by a screw, would not twist and smear the print, and 5) a new ink, made of lampblack and linseed oil, that would stick to the metal type. Paper was already available, thanks to the Chinese. It is quite amazing that Gutenberg was able to bring all this together, and not only complete his beautiful Bible by 1455, but provide printing materials and techniques that, for the most part, would continue unchanged for 300 years.

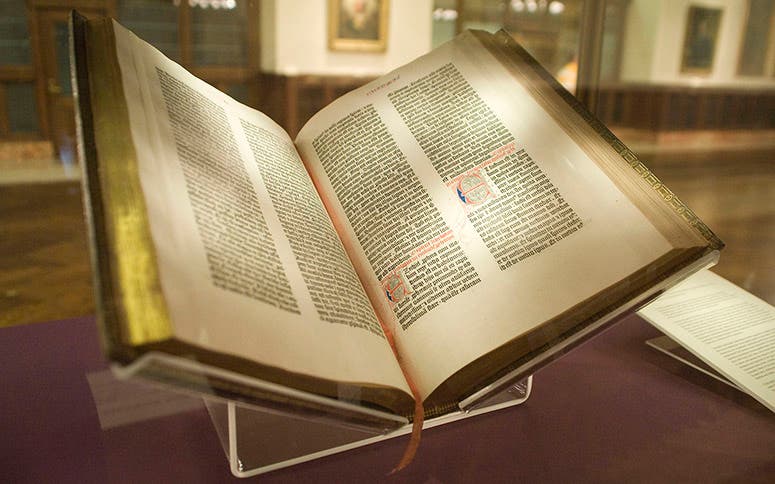

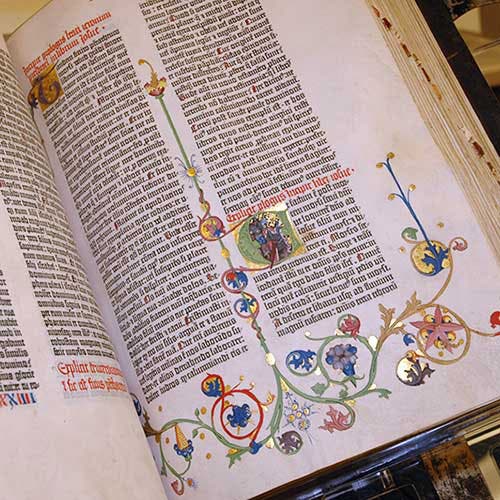

The Gutenberg Bible is of course his greatest legacy; almost 1300 pages long and bound in 2 volumes, it had a print run of about 180, with thirty of those being printed on vellum. Of those, 48 survive today in varying states of completeness, of which 12 are on vellum. As far as I know, the last time a copy sold at auction was in 1987, and that was the first volume only, which brought $5.4 million. A complete copy sold today would probably bring a hundred million dollars to the seller, if not more. Most libraries that own copies have them on continuous display and often engage in a ritual of turning the pages daily. I have seen the copies at the Beinecke Library at Yale, the New York Public Library (second image), the Morgan Library, and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Some of the copies have unadorned pages, just as they came off the press, like the one at the Library of Congress; others, especially those printed on vellum, such as the copy at the Huntington Library (third image), were beautifully illuminated after printing to look like manuscripts. Since it is the most famous book in the world, you should make it a point to see a Gutenberg Bible someday, if you have not already.

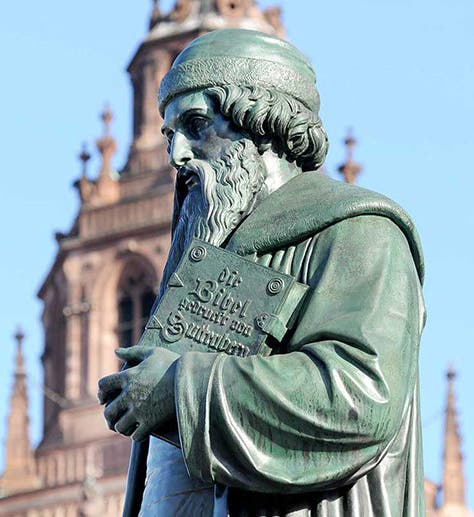

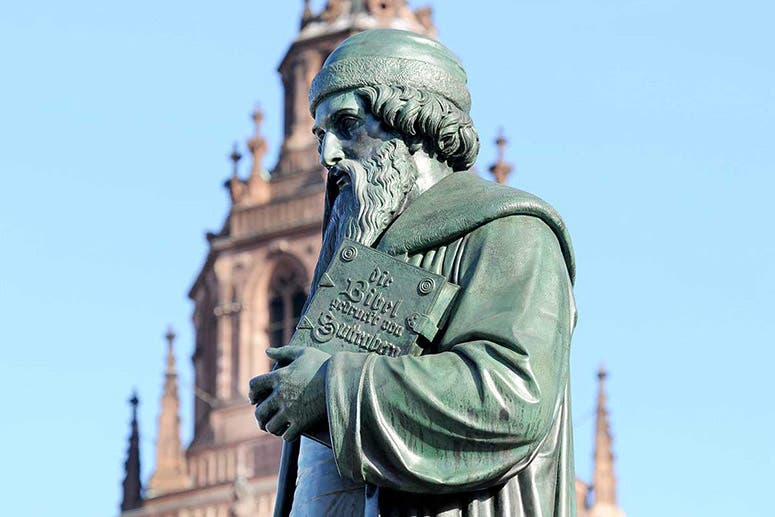

Because Gutenberg was born and died in Mainz, and printed his Bible there, the city of Mainz has a special claim on their most famous resident; there is a Gutenberg Museum there, right on Gutenberg Plaza, where they have a fine replica of an original Gutenberg printing press on display, and outside there are several statues, one of which was commissioned from the 19th-century Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and unveiled in 1837 (first and fifth images). We have written a post on Thorvaldsen, since he also sculpted one of the finest statues of the astronomer Nicholas Copernicus, on display outside the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

But Gutenberg lived other places, and each of these has erected its own statue or portrait plaque in honor of its most famous resident. Gutenberg spent some time when young in Eltville, Germany, where there is a sculpted relief portrait, and he lived in Strasbourg from about 1437 to 1444, where he must have built his first press and cast his first type, and where this is now a grand statue by a sculptor as acclaimed as Thorvaldsen, David d'Angers, put in place in 1840, just three years after Thorvaldsen’s (sixth image). It is curious that we have no idea what Gutenberg looked like, yet all the later engravings and statues show essentially the same man, with his forked beard, for which there is no evidence whatsoever.

There have been many candidates proposed for the most significant invention in the history of humankind, beginning with the wheel and fire and continuing with the magnetic compass, gunpower, and even the transistor, but it is hard not to award the grand prize to Gutenberg and moveable-type printing. Even though we may be moving out of the Age of Print after 570 glorious years, it is hard to imagine what the eras of the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment would have been like without printing, or even if they would have existed at all.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.