Scientist of the Day - Johannes de Sacrobosco

Johannes de Sacrobosco, an English cleric, astronomer, and teacher, lived in the first half of the 13th century; he was born before 1200 C.E., and died between 1236 and 1256 C.E. We know little about him, except that he taught at the Universiry of Paris, and he wrote three books, all of which were exceptionally popular for hundreds of years. One book was on the newly introduced Arabic number system, and a second was on the need for calendar reform. But today, we are going to discuss his third book, an introductory astronomy text, called simply, Tractatus de sphaera – Treatise on the Sphere. First circulated about 1230 C.E., Sacrobosco’s Sphere became the single most popular university text on astronomy, circulating in manuscript for 240 years, and then being printed again and again from 1476 all the way up to the beginning of the 17th century. We have many significant editions of the Sphaera in our collections. I was originally planning to talk about four of them all in one post, but it then occurred to me that it would be more interesting and fruitful if I discussed them one or two at a time, in perhaps three successive posts. This would allow us more time to understand just what a book on the sphere is, and also include more images from the splendid early editions that are represented in our Library.

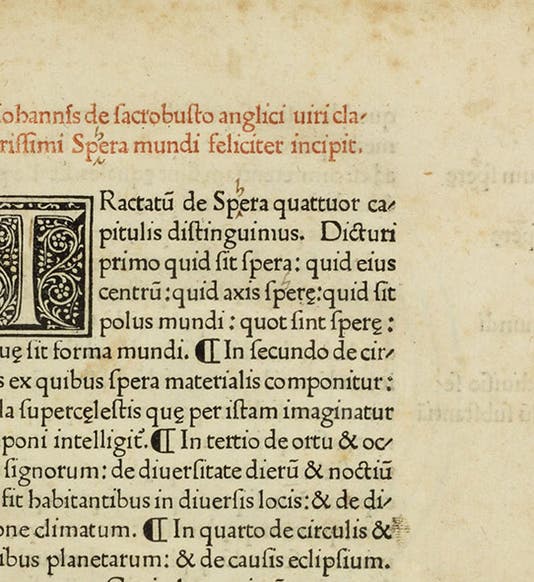

We will begin with the earliest edition we have, and the second oldest book in our collections. It was published in 1478 in Venice by Franz Renner, a printer from Heilbronn in Germany who had moved his shop to Venice. This is really a beautiful specimen of early printing, with lots of space between the lines of print, and an opening page, functioning as the not-yet-invented title page, printed in red and black (first image). You can find the author’s name, in the form of “Johannss de Sacrobusto,” and the title, “Spera mundi,” in the introductory red section. An early owner wanted an “h” in his Spera, as you can see.

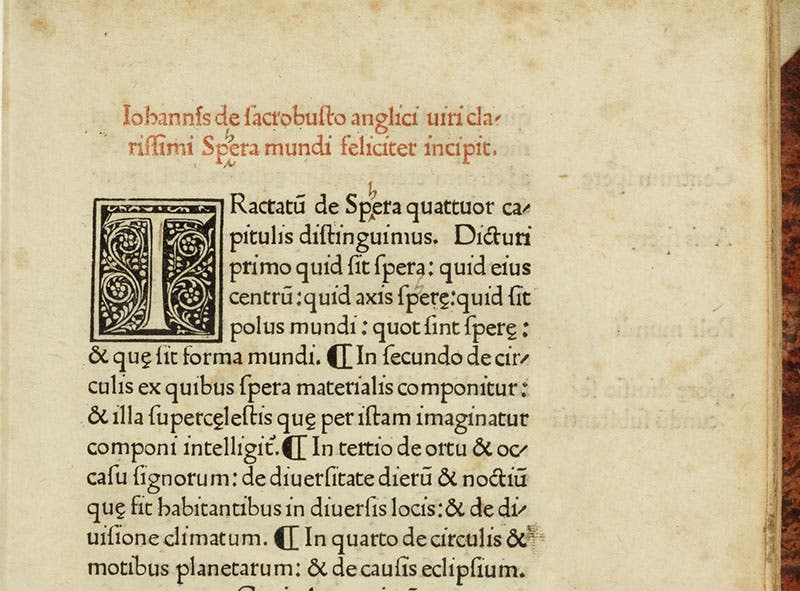

Sacrobosco’s “sphere” was in fact the cosmos, divided up into 9 individual spheres – the empyrean realm, the sphere of stars, and seven spheres for the seven planets. There is a woodcut early on that shows the sphere of spheres, with the Earth at the center (second image, above). However, the book is mainly concerned with the circles on the sphere – the equator, the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, the ecliptic, the meridian and horizon. It is often said that the book is a simple version of Ptolemy’s Almagest (140 C.E.), but there very little of what we call Ptolemaic astronomy in it – a single mention of epicycles and deferents, with no indication of how to use them to predict planetary motion.

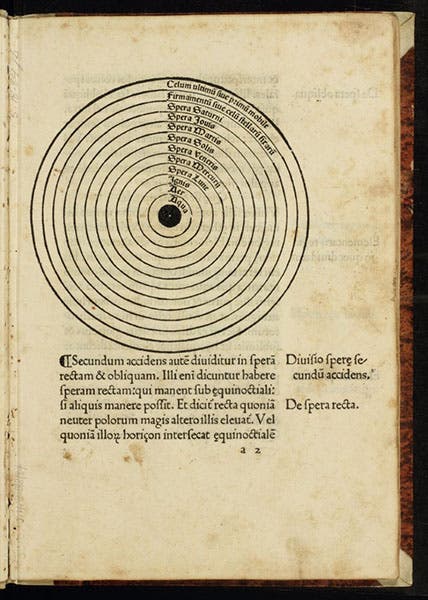

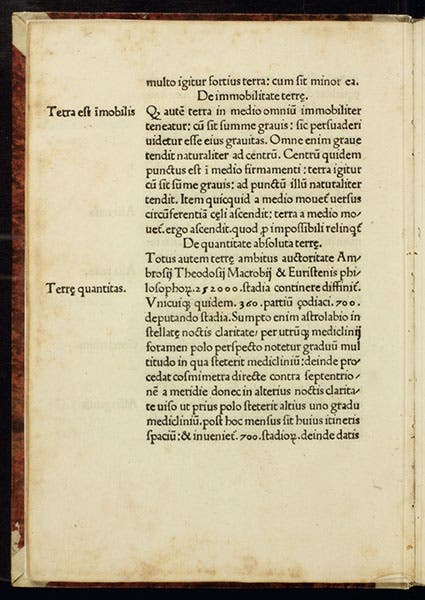

For modern readers who have come through American secondary schools and have learned that, before Columbus, everyone thought the Earth is flat, the section on the shape of the Earth is of interest, since Sacrobosco argued every which way from Sunday that the Earth is a sphere (third image, above). And given the fact that Columbus later sailed under the misapprehension that the circumference of the Earth is about 19,000 miles, it is intriguing that Sacrobosco used the figure of 252,000 stadia, calculated in Hellenistic Greece by Eratosthenes, for the Earth’s circumference, which (using a typical value for a stadium) comes to 25,000 miles, close to the modern figure (fourth image, just above).

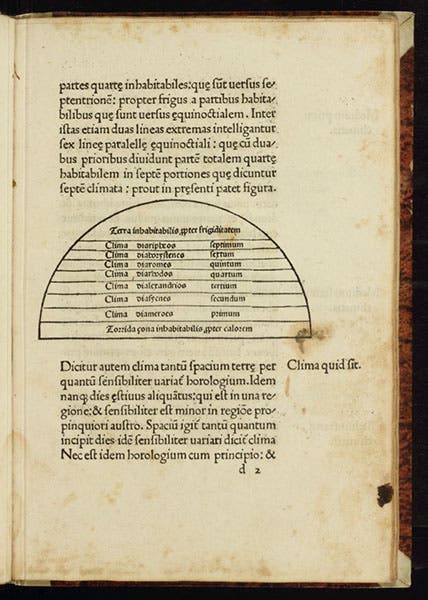

In addition to the geocentric cosmos, there are a few simple woodcuts in the printed Sphaera. We show one that presents the seven “climes” of the Earth, distinguished by the maximum length of the day, where humans can be found, excluding the equatorial and polar regions, which were considered uninhabitable (fifth image, above).

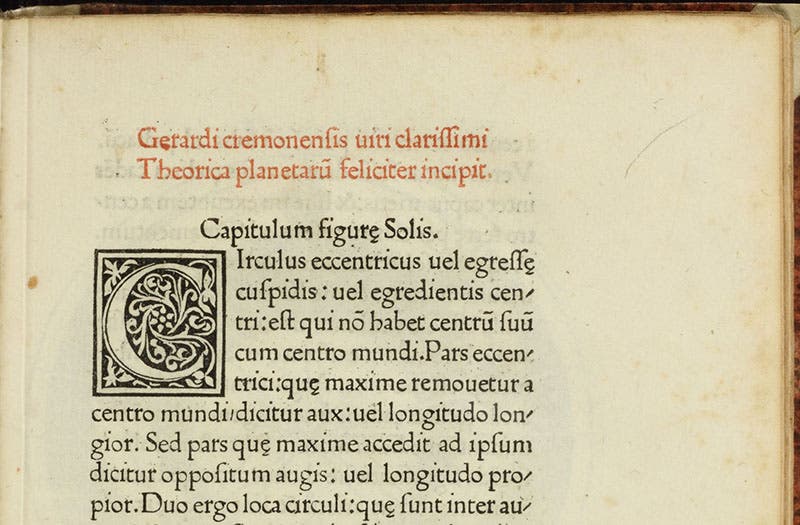

Since Sacrobosco did not explain the Ptolemaic planetary epicycle-deferent models, a separate treatise appeared in medieval times that did so. It was called Theorica planetarum – Theory of the Planets – and it was usually attributed to Gerard of Cremona, although we now know that Gerard did not write it. The Theorica was often added to medieval manuscripts of Sacrobosco, and when Renner printed the Sphaera, he appended the Theory of the Planets to it. We see here the first page of the Theorica, also printed in red and black (sixth image, above)

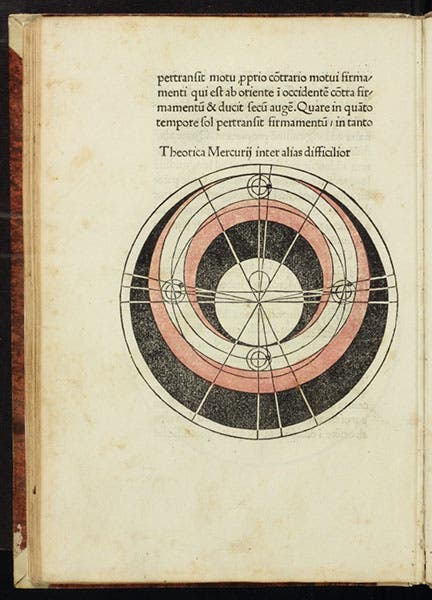

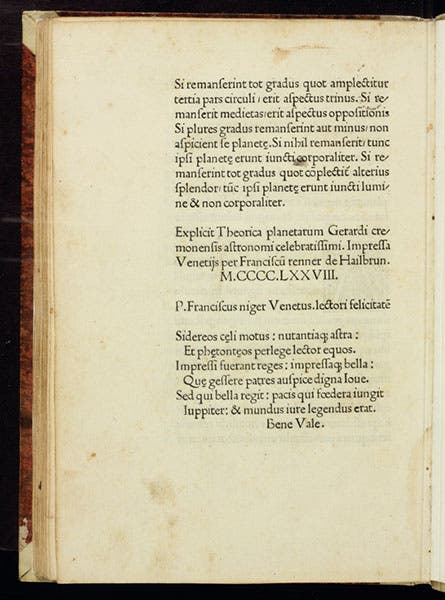

Since the Theorica has quite a few woodcuts presenting the planetary models of the Sun and Moon, the superior planets, and the maverick Mercury, as well as solar and lunar eclipses, this is the showy part of the volume, and we sometimes forget (at least I do) that these are not part of Sacrobosco’s Sphere. We show a woodcut presenting the Mercury system of epicycles and deferents, which has been gently hand-colored (seventh image, above). And finally, we display the last page of the book, with the colophon, which tells us who printed the book, and where and when (eighth image, below).

In our next installment on Sacrobosco, we will look at two slightly later editions of the Sphaera, both quite handsome, printed by Erhard Ratdolt and Ottaviano Scoto in 1482 and 1490 respectively, for which frontispieces were added, the medieval Theorica was replaced by a Theorica nova, and hand-coloring gave way (at least on this occasion) to printing in color.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)