Scientist of the Day - Johann Zahn

Johann Zahn, a German canon in the order of Premonstratensians, was born Mar. 29, 1641. Zahn had a Jesuit-like interest in natural philosophy, and he is best known for a large folio on optics that he published in 1685, Oculus artificialis teledioptricus sive Telescopium. But since we don't have a copy of that work in our collections, we are going to turn to a Zahn publication we do have, his Specula physico-mathematico-historica notabilium ac mirabilium sciendorum (Physical-mathematical-historical mirrors of notable and wonderful things that can be known, 1696). This too is a large folio, in three volumes (bound as two in our set, with beautiful stamped vellum boards and clasps that are still intact.) The Specula is just about the last of a genre that might be called the Baroque scientific encyclopedia, an invention of the Jesuits, and we have many examples in our collections by the likes of Athanasius Kircher, Gaspar Schott, and Giovanni Battista Riccioli. The first volume of this non-Jesuit work is entirely about astronomy, and we had this volume scanned so that we could show you some of the many full-page and double-page engravings. (Volumes 2 and 3 will be scanned in due course, and will perhaps be the subject of a follow-up post).

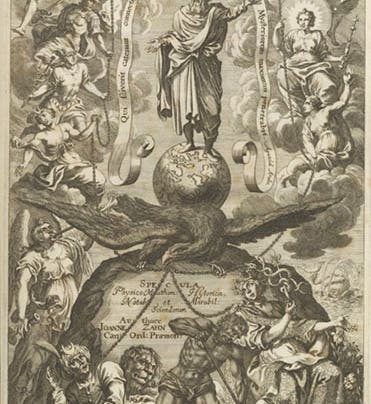

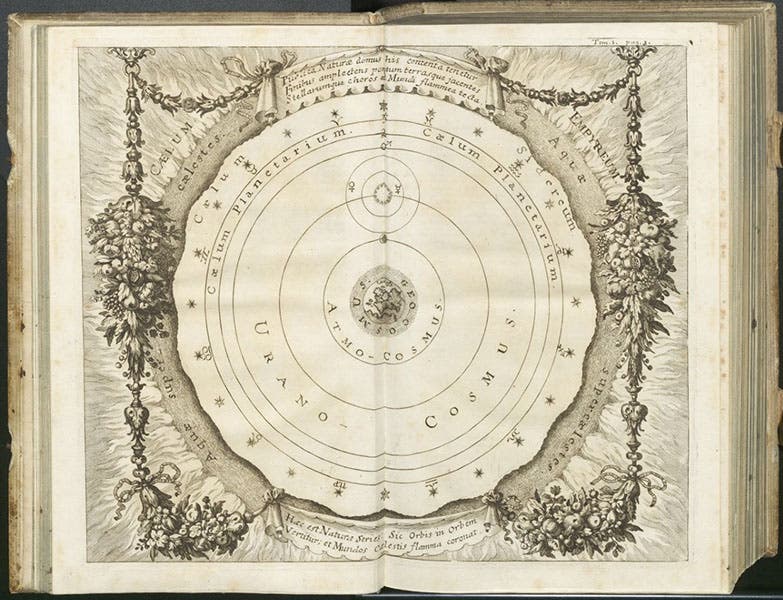

Volume 1 of Zahn’s Specula has a rich engraved title page; we don’t have the room or the inclination to analyze it in detail, so we will only point out that the 7 planets at the top are intended to correspond to the 7 metals down below, in a macrocosm/microcosm kind of way. For a book named Specula, there is a surprising dearth of mirrors in evidence. So we are going to turn our attention to the plates showing the cosmos and the planets. The plate with a diagram of the cosmos is right at the beginning (third image, below), and it shows that Zahn was happy to have Venus and Mercury orbit the Sun, but that is as far as he would go with heliocentric astronomy. The Earth (labelled Geocosm) is at the center, and the remaining planets orbit the Earth. One interesting feature of this diagram, not typical of most portrayals of the cosmos, is that the sphere of stars is slightly scalloped, in order to provide a seabed for the waters above the heavens mentioned in Genesis. Zahn probably got this idea from the engraving of the cosmos in Gabriele Beati's Sphaera triplex (1661), which you can see as the first image in our post on Beati.

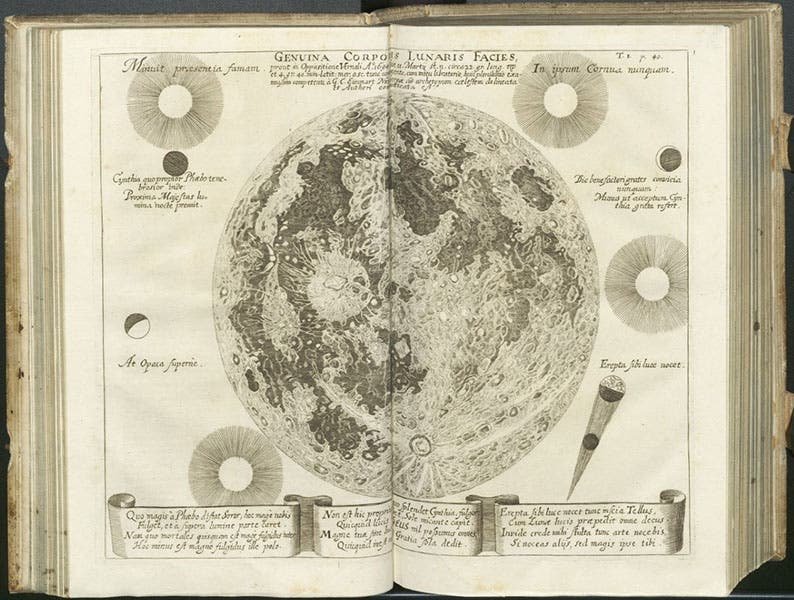

There are two maps of the Moon in this volume, neither original to Zahn. One is a map by Johannes Hevelius, carefully copied from his Selenographia (1647); we do not show it here, because it is identical to the engraving in Hevelius’ book, which we featured in a post on Hevelius (the sixth image there). But the other lunar map is worth reproducing, because as far as I know, it was published in Zahn’s book for the first time, and was never published again. The map was the work of George Eimmart, a German cartographer, who must have been known to Zahn (fourth image, below). Eimmart's map is not great as a map, since many of the craters are misplaced and some are missing entirely. But if you view it as an impression of the Moon, rather than a map, it is quite successful, since the Moon when full does indeed seem to shimmer with light, and looks much more like Eimmart’s moon than Hevelius’s map.

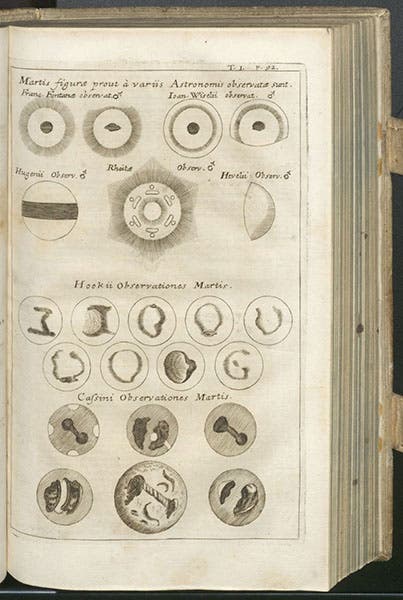

Each planet except Mercury has its own engraved plate, and we show several of those here. It is important to note that Zahn does not claim to have been an astronomer himself, so his plates show the planets as others saw them, and that is the one of the chief virtues of the book, since it gathers together in one place a variety of separate 17th-century observations. For example, the plate on Mars (fifth image, below) shows, at the top, drawings by Francesco Fontana, Christiaan Huygens, and Hevelius, while at the bottom we see the sequential observations of Giovanni Domenico Cassini and Robert Hooke, which were copied from a plate in a very early issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

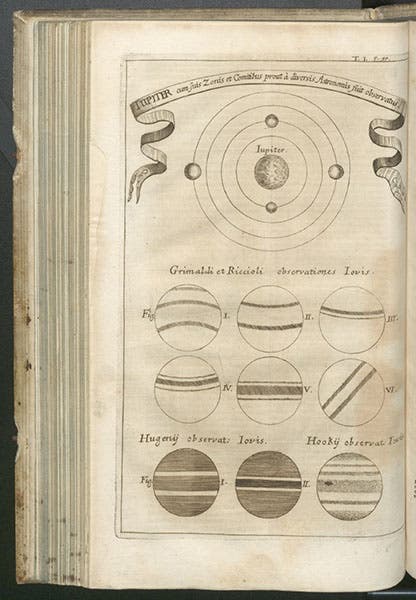

The plate of Jupiter (sixth image, below) shows the Jovian observations of a variety of contemporary astronomers. The first six views at the bottom were made by Franceso Grimaldi and Riccioli and appeared, looking very much like this, in Riccioli’s New Almagest (1651). Below those are two observations by Christiaan Huygens, taken from his System of Saturn (1659; you can see his engravings of Jupiter, and Mars, at our post on Huygens, next-to-last image), and one by Robert Hooke, showing Jupiter’s red spot. The top part of the engraving, however, contains a novelty – circling around a sketch of Jupiter borrowed from Hevelius, the four Galilean moons are shown as orbs, and of different sizes. I am guessing, given his track record, that Zahn borrowed this concept from somewhere, but I confess I do not know where that might have been.

Rather than show the plates depicting Venus and Saturn, I thought I would use our last image – a detail of a larger engraving - to remind us that Zahn was a canon in the Catholic Church. One of the first plates in the volume tells us where the cosmos with its variety of planets came from, as God says: Fiat! Let there be light! And there was light.

There is no portrait of Zahn that I have been able to find. All the Jesuit encyclopedists have portraits; it is a pity that the Premonstratensians did not make more of an effort to provide an image of their only encyclopedist of note.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.