Scientist of the Day - Johann Theodor de Bry

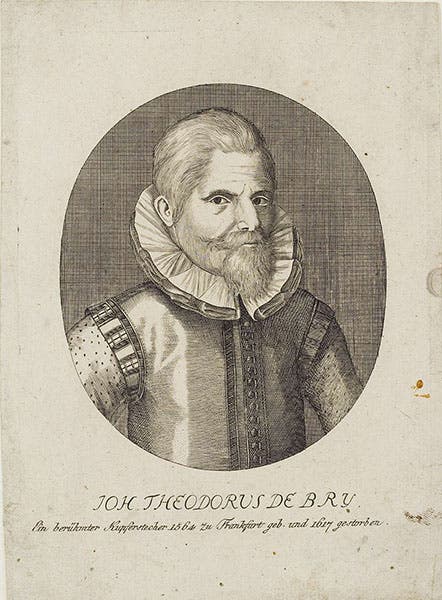

Johann Theodor de Bry, a German engraver and printer, died Jan. 31, 1623, at the age of 61. His father, Theodor de Bry, was also a printer and engraver, whose best-known publishing effort was the America series, also called the Grand Voyages, which began in 1590 with Thomas Harriot’s A Briefe and True Report on the New Found Land of Virginia, with engravings by de Bry based on drawings by John White. The series continued on for 13 volumes. We do not have Harriot's book, or any of the America series, in our Library, although there is a beautiful set not far away, in the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. We did a post on White just last year, where you can see some of the engravings the elder de Bry executed and printed. Johann Theodor helped his father with some of the engravings for the early volumes, and when Johann died in 1598, the younger engraver and his brother (who died in 1609) took over and completed the set.

The younger de Brys also published another set, the Petite Voyages, containing narratives of travels to the East Indies (called petite, not because the voyages were smaller, but because the volumes were shorter). Johann also published a very popular Florilegium (1612), with splendid engravings of flowers, which we do not have in our collections (florilegia were distinguished from herbals in that they were not concerned with the medicinal properties of plants, but rather with the visual appeal of the flowers). I have seen several copies of the Florilegium; it is a beautiful work especially when uncolored, so that the engraving stands out.

Johann Theodor continued to engrave and print books at the family establishment in Frankfurt. HIs daughter married a young man named Matthaeus Merian, and the son-in-law, also a talented engraver, joined the firm. Around 1617, de Bry and Merian were drawn into the circle around Frederck V, the young Elector of the Palatinate of the Rhine, one of the constituent states of the Holy Roman Empire, with a court in Oppenheim. This was at a time when two anonymous treatises appeared touting a secret society called the brothers of the Rosy Cross, or the Rosicrucians, which was (so the treatises tell us) steeped in mysticism, alchemy and the cabala. Rosicrucianism was apparently popular at the Electoral court.

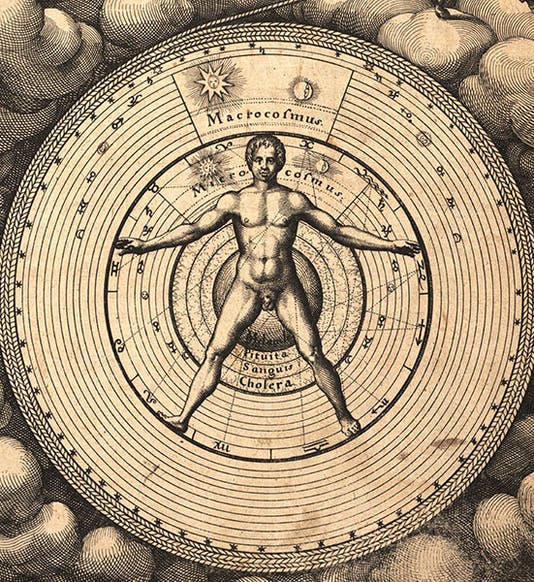

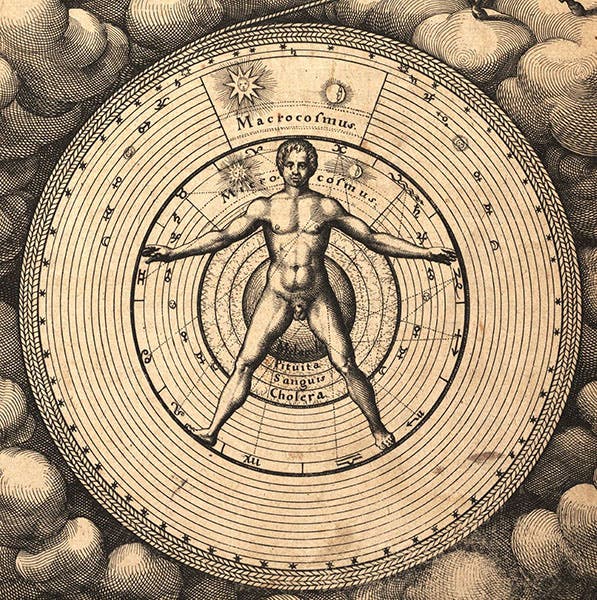

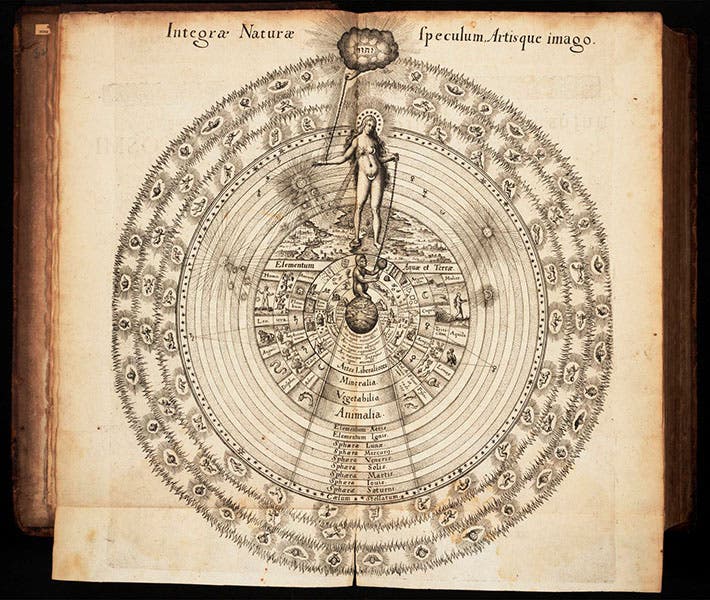

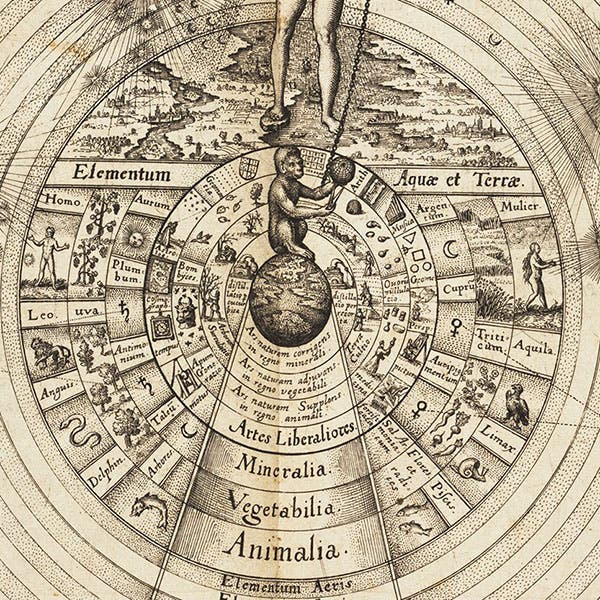

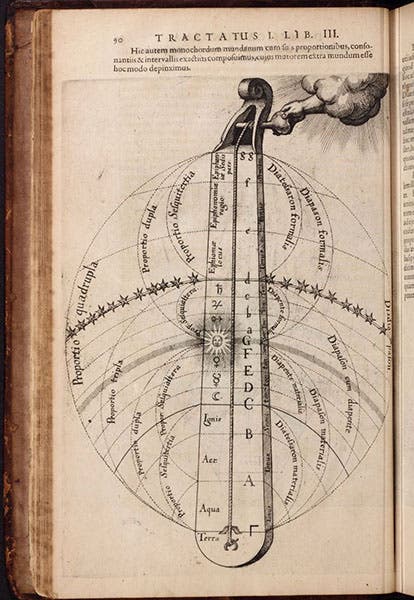

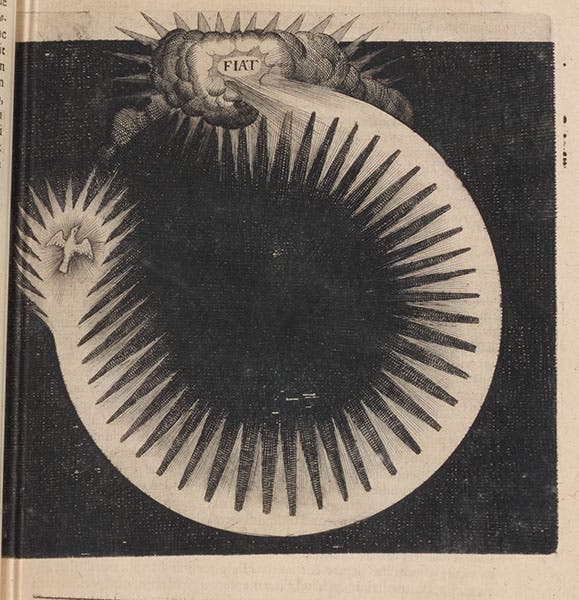

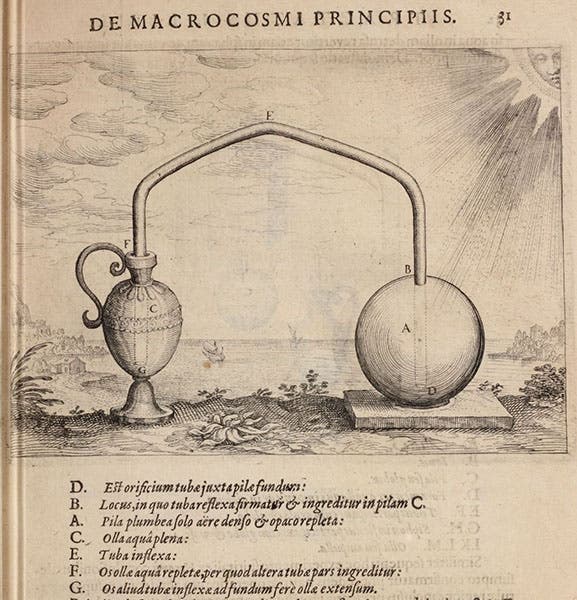

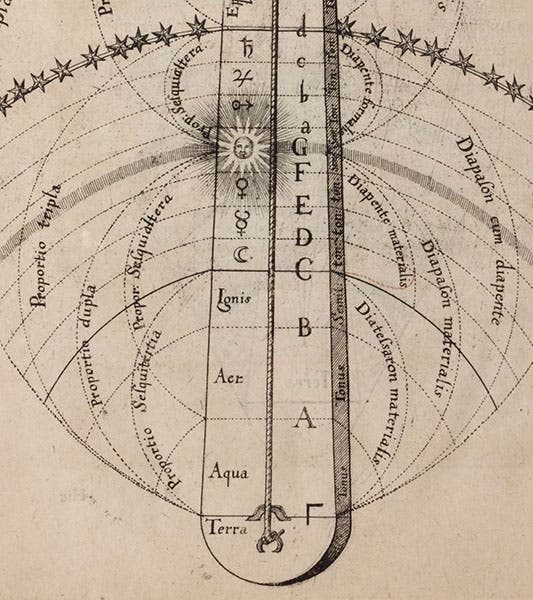

We don't know exactly how Johann Theodor became involved with Frederick V, but he moved his establishment to Oppenheim in the Rhineland and proceeded to engrave and print one of the most celebrated books touting the virtues of the Renaissance magical world view, with its emphasis on numerology, alchemy, astrology, and musical proportion. The book was Robert Fludd's Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica … historia (History of the Macrocosm and Microcosm, 1617-26), and its many engravings, initially all by Johann Theodor, depicting earth-centered macrocosms, human or elemental microcosms, cosmic monochords, and magical machines are commonly used to illustrate discussions of Renaissance magic, even though it was published when that world-view was rapidly being replaced by the work of Johannes Kepler (a vocal opponent of Fludd), Galileo Galilei, and the mechanical philosophy of René Descartes.

Detail of fifth image, showing the “tunings” that connect the elemental and celestial realms; diatessaron, diapente, and diapason mean musical intervals of a fourth, a fifth, and an octave, respectively, engraving by Johann Theodor de Bry, in Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris … historia, by Robert Fludd, Book 1, p. 90, 1617-21 (Linda Hall Library)

Fludd, an Englishman, was more than happy to have his book published in Oppenheim by de Bry. He had discovered to his dismay that English publishers were going to demand hundreds of pounds up front to defray the cost of engraving; de Bry was happy to pay Fludd a fee and take on the cost of engraving himself. The partnership certainly worked out for both. We have published a post on Fludd.

The court at Oppenheim was short-lived. Frederick was elected King of Bavaria in 1618, and then just as rapidly removed, as the Thirty-Years War broke out, and de Bry moved his press back to Frankfurt. He published one other Rosicrucian-style book, the alchemical emblem book, Atalanta fugiens (1617), by Michael Maier, with splendid engravings my de Bry and Merian. We do not have that book in our collections either. Since we know little else about de Bry, we show here some of his handiwork, engravings from our copy of Fludd's History of the Macrocosm and Microcosm. We included some of these in our post on Fludd, so for this occasion, we have provided details of a few engravings, so that you can appreciate de Bry's engraving style.

Johann's Theodor's final claim to fame is that his son-in-law, Matthaeus Merian, was in turn the father of Maria Merian, the artist responsible for the lovely Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam (1705). Maria, an intrepid and talented woman, has become by far the most famous member of her distinguished family, but she owes a real genetic debt to her grandfather, Johann Theodor de Bry.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.