Scientist of the Day - Johann Jakob Kaup

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

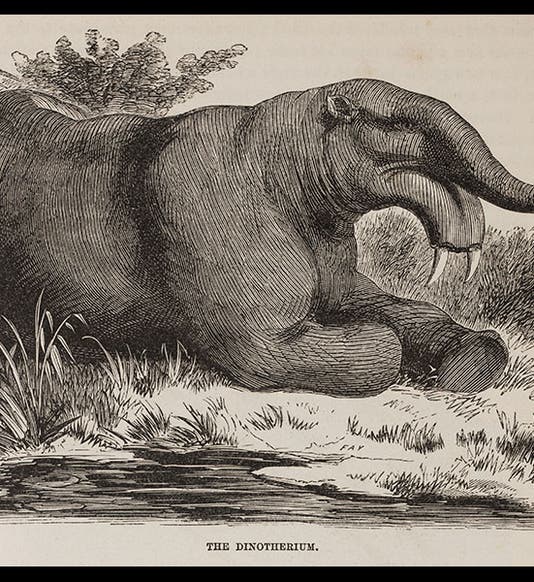

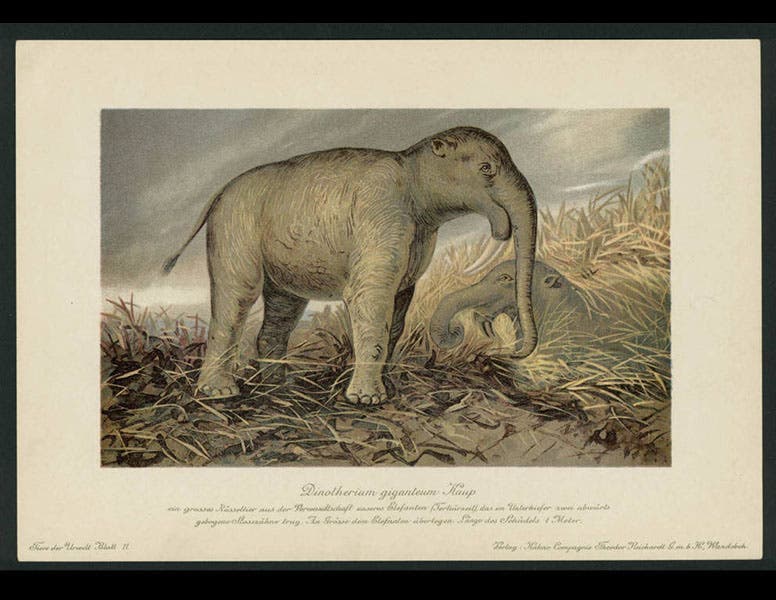

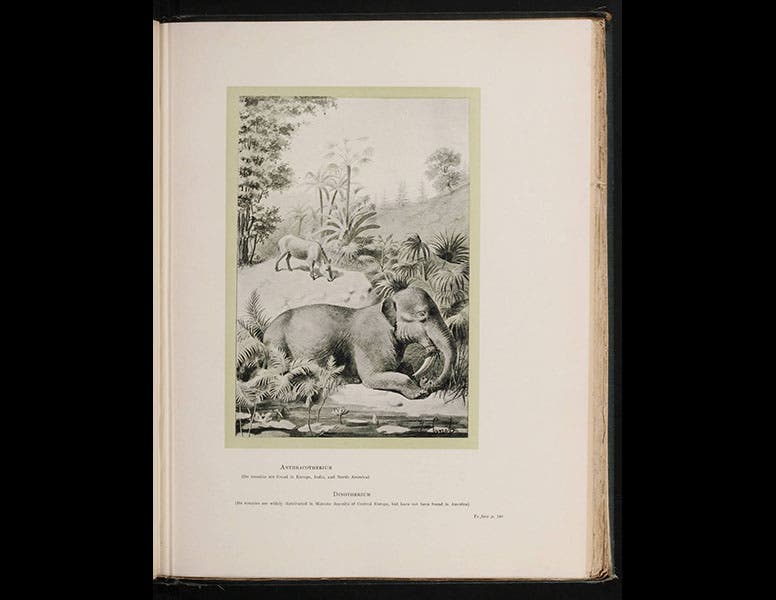

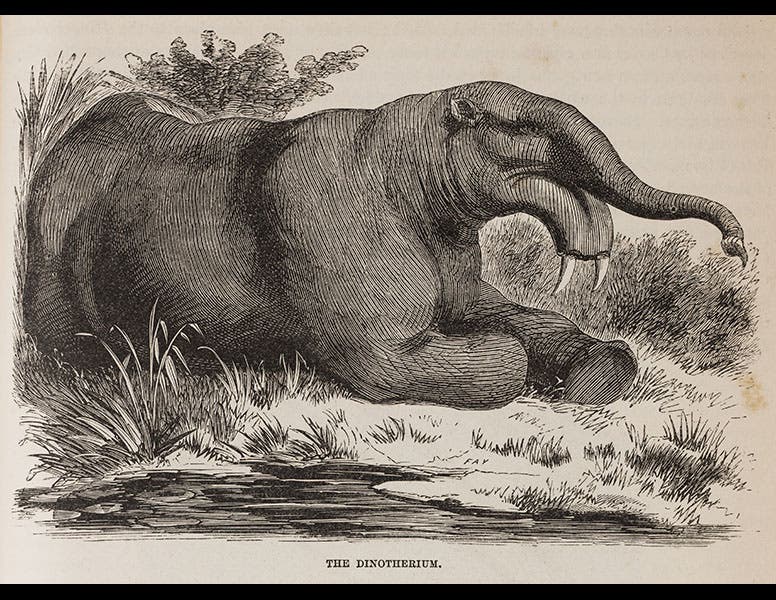

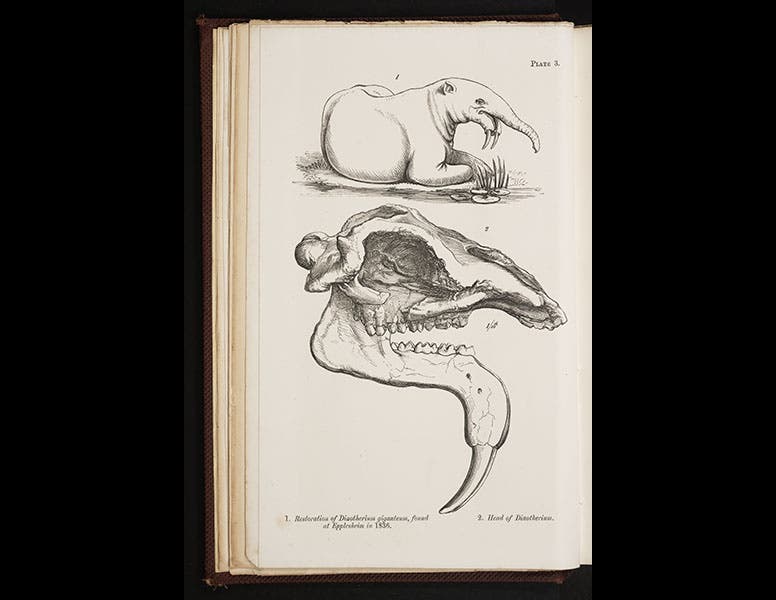

Johann Jakob Kaup, a German paleontologist, was born Apr. 20, 1803, in Darmstadt. In 1829, in a place called Eppelsheim, about 40 miles from Darmstadt, Kaup uncovered the fossil remains of a huge, elephant-like animal. Its most distinguishing features were its gigantic size--bigger than a mastodon--and a pair of enormous downward-facing tusks that grew out of the lower jaw, making it kind of a pachydermal backhoe. He called the extinct creature Dinotherium giganteum, "terrible gigantic beast", and announced it in several publications before 1836. William Buckland in England picked up on it right away; he included a picture of the lower jaw in his Bridgewater treatise, Geology and Mineralogy considered with reference to Natural Theolory (1836), and in later editions, he added a life restoration and an image of the entire skull (second image). The Dinotherium (now spelled Deinotherium, for some reason) soon became a staple of prehistoric lore. Samuel Goodrich included a wood engraving in his Illustrated Natural History of the Animal Kingdom (1859; first image), and other popularizers of the prehistoric followed suit. You can find, for example, a dinotherium on a Reichart Cocoa card, published in the early 20th century (third image), and another in Henry Knipe’s Nebula to Man (1905; fourth image).

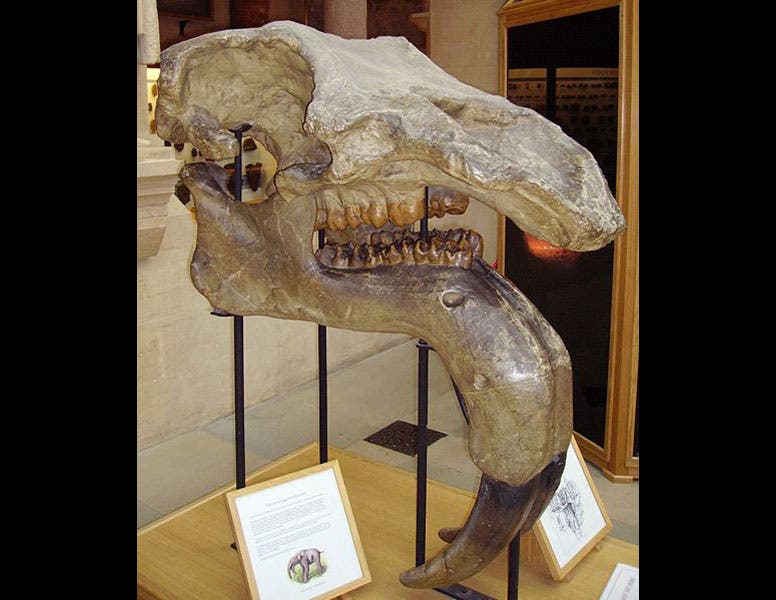

You can also find Deinotherium skulls in many natural history museums, where they will surely impress you with their size and those unlikely downward-thrusting incisors. There is one in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (fifth image), and another, perhaps Kaup's original find, at the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt (sixth image).

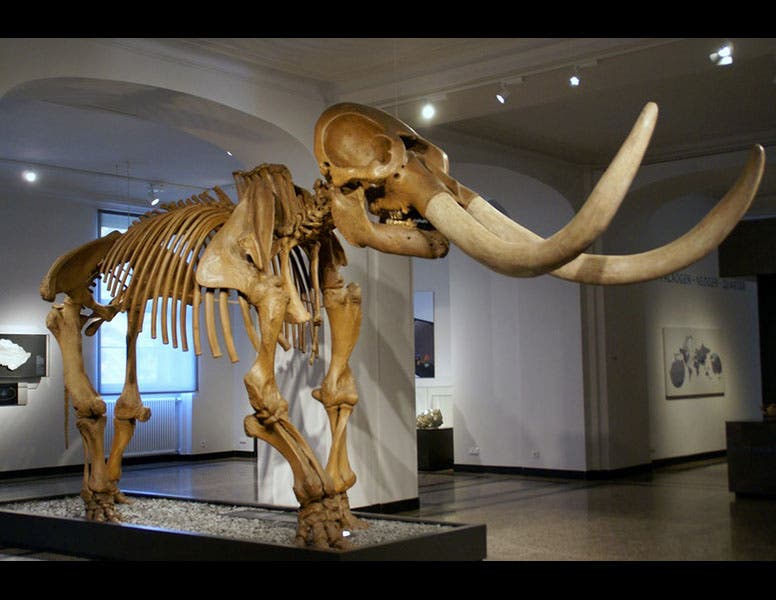

Kaup has one other claim to fame, one that is, for historians, perhaps of even more consequence. When the Peale Museum was being broken up in 1854, Kaup purchased Peale’s mastodon, which was the second-earliest extinct quadruped ever mounted, thus saving it from a second extinction. It is now on display in the Darmstadt Museum, not too far from the Deinotherium skull (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.