Scientist of the Day - Johann Glauber

Johann Rudolf Glauber, a German chemist and apothecary, was born Mar. 10, 1604. Glauber was an interesting figure in the history of chemistry in that he was not a physician or an academic, but an artisan. He earned his living by selling chemical preparations. That in itself is not so unusual – that is what apothecaries did, after all – but Glauber was unique in that he was literate as well, writing dozens of books about chemical matters. Moreover, his books were read and cited by other chemists, which makes him an extraordinary apothecary indeed.

Glauber started his career in Germany, working for a variety of patrons in a half-dozen cities, venturing also to Basel and Paris, before moving to Amsterdam in 1640. He went back to Germany a few times, once fleeing bankruptcy, but finally settled down for good in 1656 in the great Dutch city on the mouth of the river Amstel. He died in 1670.

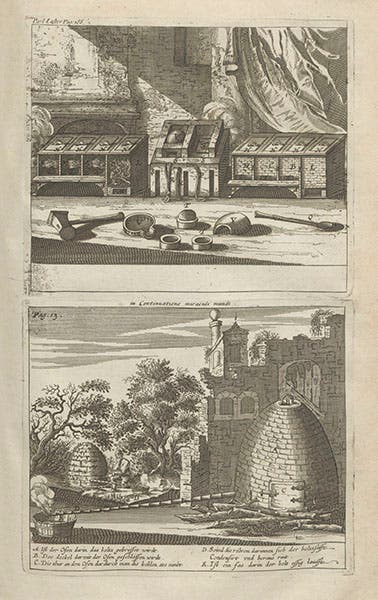

Glauber rarely gave away his trade secrets in his books, since that would have been cutting his lifeline, but he did feel free to discuss his equipment, such as in his popular book on "philosophical furnaces". The laboratories in his house in Amsterdam were so elaborate and well-equipped that his home was often visited by dignitaries, much in the way that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s house in Delft became a necessary destination for any nobleman on a grand tour. We have six books by Glauber in our collections, three of them editions of his New Philosophical Furnaces, in Latin, French, and English (1651-59).

Glauber is best known for discovering a salt that he called "sal mirabilis"; we now know it as “Glauber's salt," or sodium sulfate. The salt is not all that mirabile, since it is found naturally in many locations, and is also a byproduct of the manufacture of hydrochloric acid, but it was a popular medicine of the time, since it served as an efficacious but mild laxative.

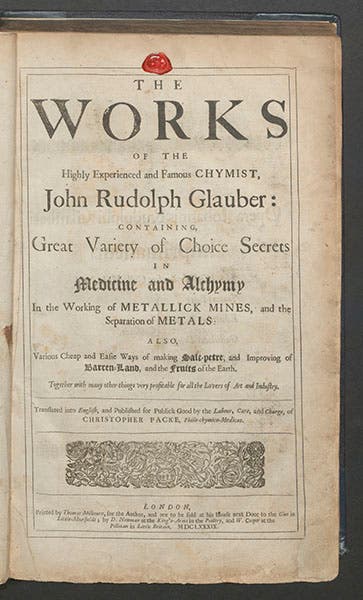

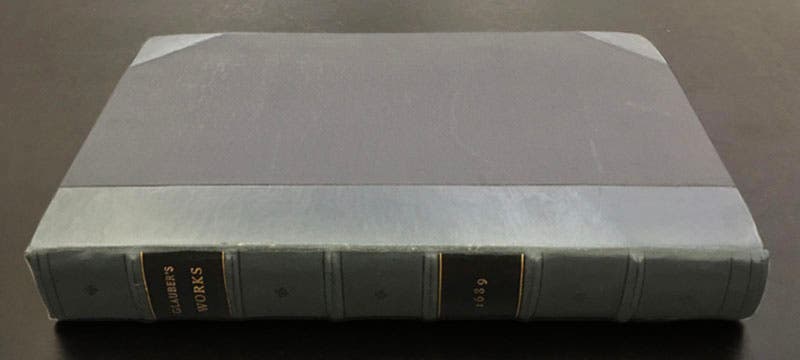

One of our Glauber books, a translation of several of his books into one English volume, is especially handsome, partly because it is a large folio, and partly because, some time ago, it was rebound in a handsome two-tone blue half-calf binding (fifth image).

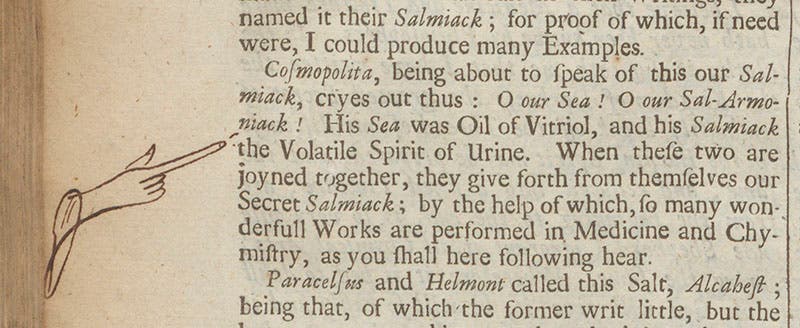

Four of our illustrations today are taken from this edition, showing some of Glauber’s philosophical furnaces (first and fourth images). Our copy was studied carefully by one former owner who was especially fond of “manicules,” those tiny finger-pointing hands in the margins that indicate some well-appreciated word or phrase. We show you one of these from Glauber’s Works, a very well-drawn one, should you collect fine manicules (sixth image).

Five years ago, when writing about a 19th-century nature printer, Henry Bradbury, we noted a connection between a book published by Bradbury and the façade of the Kansas City Public Library Parking Garage. We promised there to discuss this connection more “in the coming months,” and now five years have passed. So let us make good on our promise, with apologies for the slight delay.

When the Kansas City Public Library (KCPL) was rebuilding their downtown location in 2004, the Library Board wanted to make a public statement about the importance of books, and they chose to erect a number of giant book spines as a façade for their parking garage, with the titles on the spines those of classic books nominated by the public and chosen by the board.

Rather than design the spines from scratch, they chose to photograph real rare book spines, on which they would then insert new titles. They selected 22 volumes from the Linda Hall Library’s History of Science Collection to provide these prototypes. We have a record of the photos that were taken, so it is possible to match up the pictures of our books with the final products on the garage wall. Thus we can inform you with some confidence that the spine of The Works of the Highly Experienced and Famous Chymist, John Rudolph Glauber appears on the KCPL garage as Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird (seventh image). Now that’s mirabile!

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.