Scientist of the Day - Joachim Camerarius the Younger

On May 8, 2017, we featured Andrea Alciato as our Scientist of the Day. Alciato invented the emblem, a clever combination of image, motto, and epigram that proved to be very popular in 16th-century humanist circles. Alciato included a few animal and plant emblems, and when later emblem writers added many more natural objects, it had a decided impact on the way contemporaries viewed the natural world, so much so that the period from 1550 to 1650 has been called the era of emblematic natural history. We mentioned in our Alciato essay that the most important emblem book devoted to animals and plants was the Symbola et Emblemata of Joachim Camerarius, and we offered to look more closely at Camerarius when his birthday rolled around on Nov. 6. That day is now upon us.

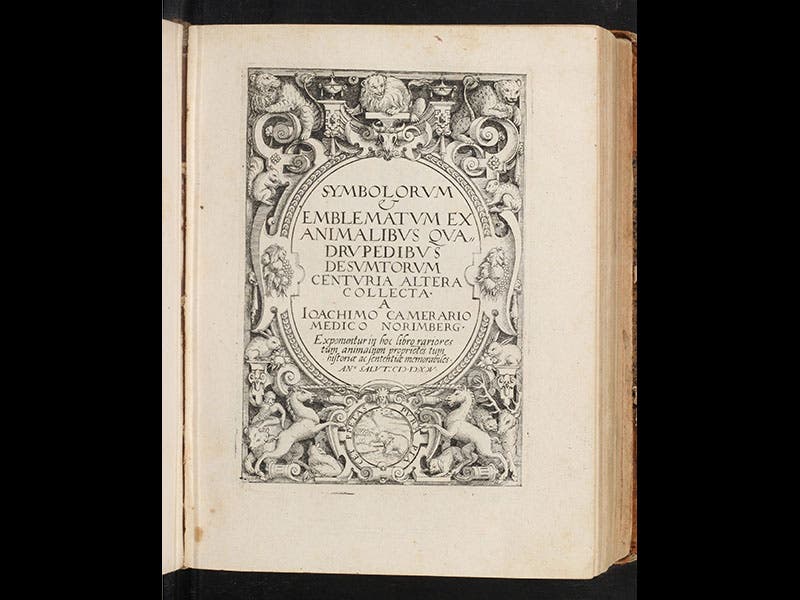

Joachim Camerarius, a German botanist, physician, and humanist, was born on Nov. 6, 1534. Camerarius the Younger, so known because his father, Joachim the Elder, was a prominent humanist during the days of Martin Luther and Philip Melanchton, issued his emblem book in four parts, or centuries, each with 100 emblems. The first century was devoted to plant emblems, which was not surprising, given that Camerariuis was a gardener of note and had just published an illustrated guide to plants, the Hortus medicus et philosophicus (1588; we have this work in the Library, along with the Symbola et Emblemata). The plant emblem volume came out in either 1590, if you believe the title page, or 1593, if you are swayed by the date of a prefatory letter. The second century (1595) was concerned with quadrupeds, mostly mammals, with a few reptiles thrown in. Century three (1596) provided 100 bird emblems, and century four (which came out in 1605, after his death) dealt with emblematic fish and water-dwelling animals.

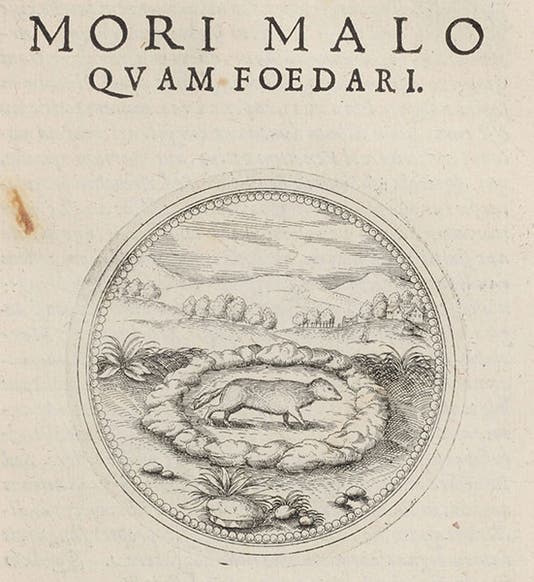

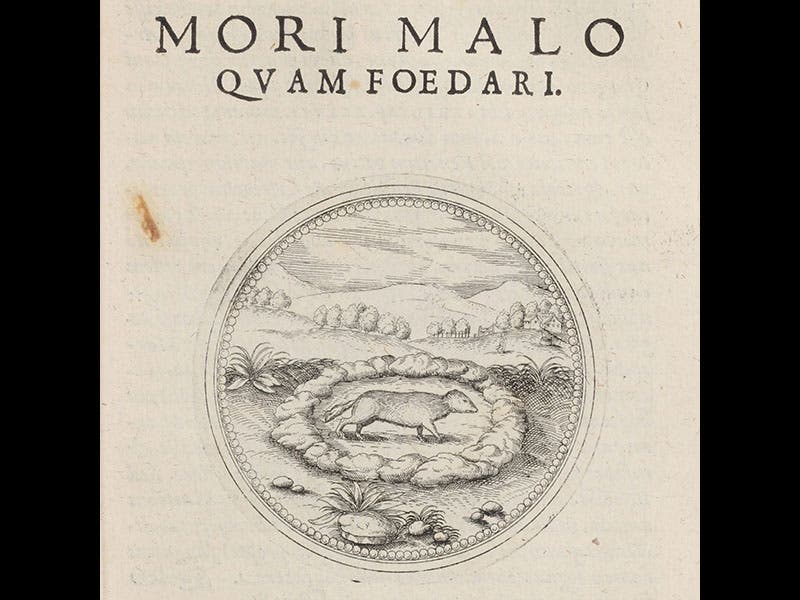

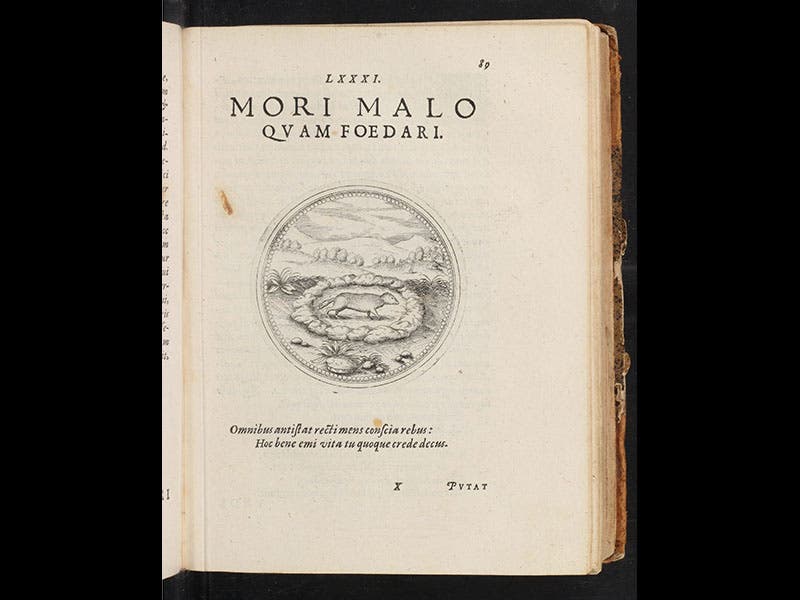

We have chosen our examples today from the volume on quadrupeds. Our first emblem (shown twice, full page (third image) and in detail (first image)) depicts an ermine pacing about inside an enclosure. The ermine knows that when its fur turns white, hunters will try to kill it, and it also knows that if it urinates on its fur, its coat will be ruined and the hunters will look elsewhere, but the personal cost of this desecration would be great. The motto shows the ermine's conclusion: "Mori malo quam foedari"--"better to die than be dishonored". From this time forward, the ermine will represent a moral dilemma--when do we make a stand for our beliefs, and when do we sacrifice them for our continued existence?

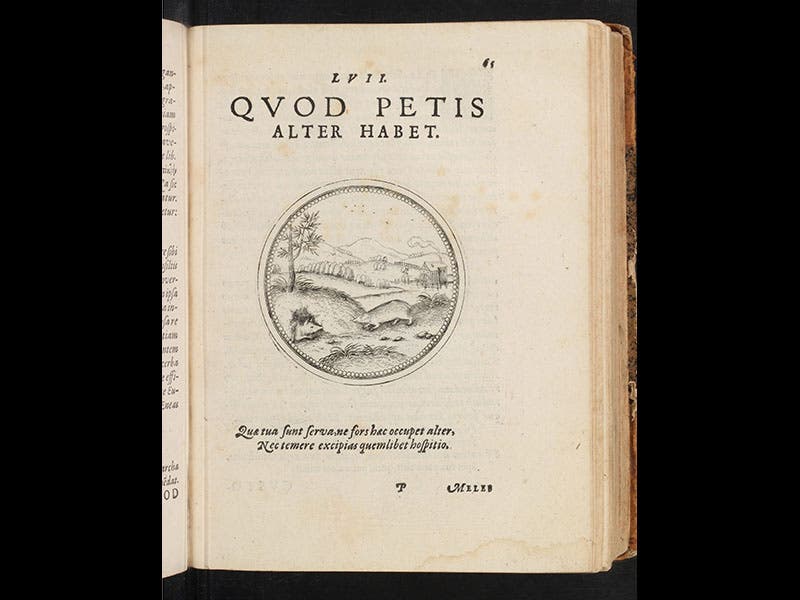

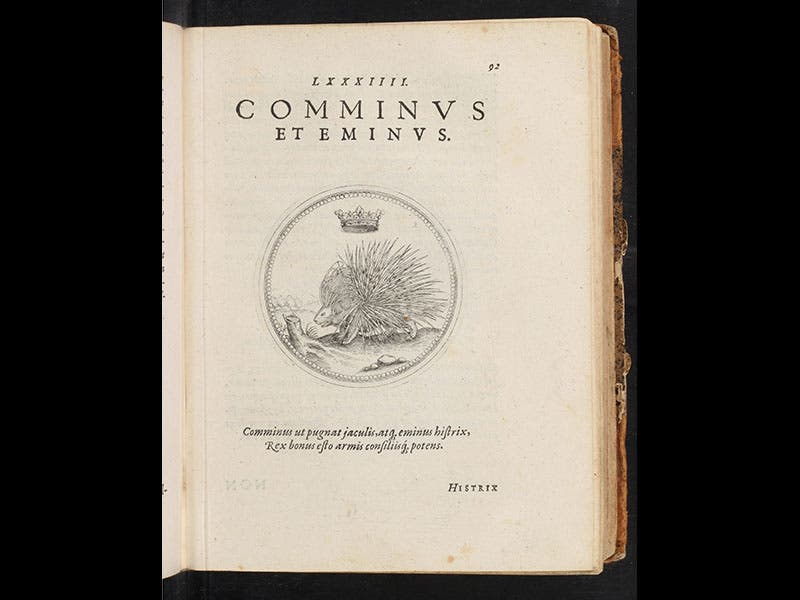

Another emblem (fourth image) depicts a badger coming home to his den, in which now sits a fox. Pliny tells us in his Natural History that a fox, wanting to avoid the labor of digging its own den, will often appropriate the lair of another animal. The motto is: "What you desire, another has". Or, as the Rolling Stones put it, "You can't always get what you want." Our third emblem (fifth image) shows a porcupine, with an abstruse motto: "Cominus et eminus"--"hand to hand and from afar." This is actually an impressa that Camerarius appropriated, the personal device of King Louis XII of France. Louis was convinced by his impressa designer that a porcupine was a fine symbol for leadership, because it could defeat its enemies in a close encounter and also from a distance, by flinging its quills, just as a proper king could prevail via hand-to-hand combat and through diplomacy from afar.

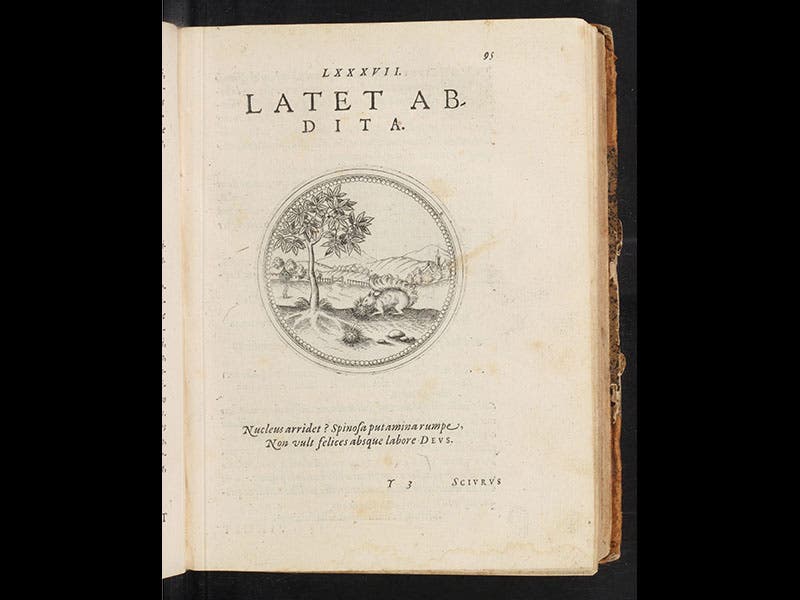

The last emblem above (sixth image) shows a squirrel trying to get through the husk of a chestnut to reach the meat within. The motto – “it lies concealed”--means that sometimes hidden treasures are worth the effort.

Camerarius’s proposal that every animal, bird, fish, and flower has a hidden meaning was very attractive to natural historians, and it is telling that Ulisse Aldrovandi, who compiled a dozen folio volumes on animals that appeared between 1599 and 1648, included every one of Camerarius’s animal emblems in his descriptions. For Renaissance natural historians, animals and plants were part of an intricate network of meanings and signs, and emblems were an important element of that world-wide web.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.