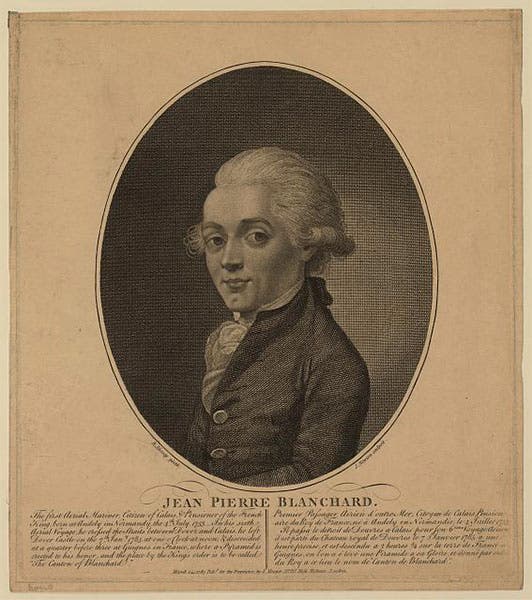

Scientist of the Day - Jean-Pierre Blanchard

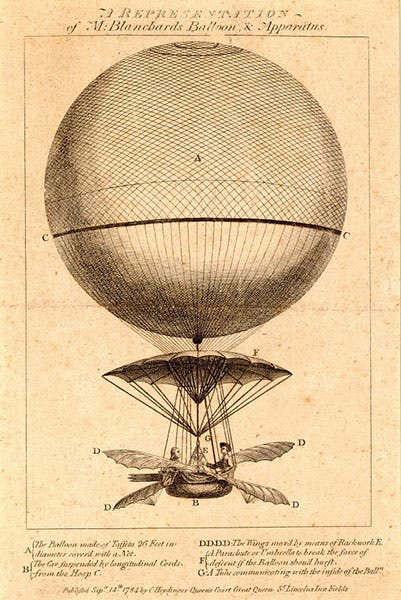

Jean-Pierre Blanchard, a French balloonist, was born July 4, 1753. The Golden Age of Ballooning began on Nov. 21, 1783, when Pilâtre de Rozier and François d'Arlandes soared aloft in a hot-air balloon made by the Montgolfier brothers. They launched from the Château de la Muette just outside Paris and floated for some 5 miles. Just over a week later, Jacques-Alexandre Charles and Nicolas Robert ascended to 3000 feet from the Tuileries in Paris, this time in a hydrogen balloon. Blanchard was caught up immediately in balloon frenzy, designed his own hydrogen balloon, complete with "oars" to swim through the air and an always-open parachute to slow descent should the gas bag spring a leak, and headed for the skies (third image). He made his first ascent in a hydrogen balloon on Mar. 2, 1784, lifting off from the Champ de Mars. If there is a surviving contemporary image of that ascent, I have not seen it.

The difference between Blanchard and the Montgolfier brothers and Jacques Charles is that Blanchard was in it for the money. He was the first barnstorming balloonist who charged admission for his ascents and seems to have given the public (who showed up by the thousands) their money's worth, especially on the first ascent, when a military student demanded to come along and attacked Blanchard and the balloon with a sword when he was refused. The somewhat bloodied Blanchard proceeded with the flight anyway, which I am sure delighted the crowd.

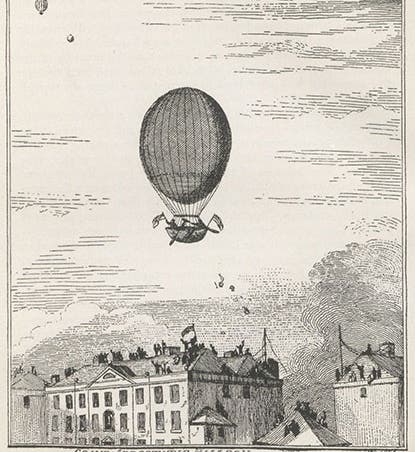

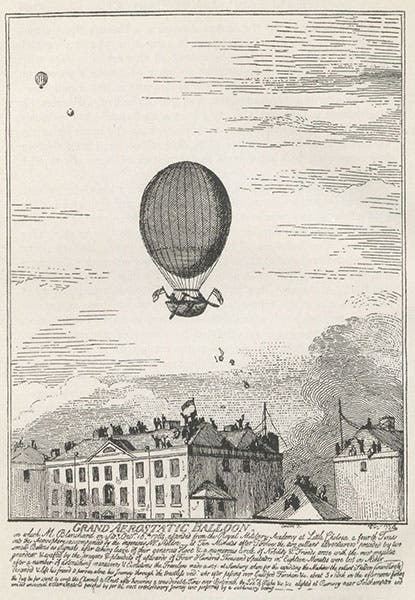

Seeking larger paydays, Blanchard travelled with his balloon to England in August of 1784 and began to organize public ascents there. He made one ascent from Chelsea, for which (so it is recorded) 400,000 people showed up. He made the ascent with an English physician, who was added to the gondola to increase local interest. An engraving recorded the event, which took place on Oct. 16, 1784 (first image). Blanchard then ascended with another physician, John Jeffries (an ex-American, actually), on Nov. 30, 1784, and this time they wafted all the way from London to Kent.

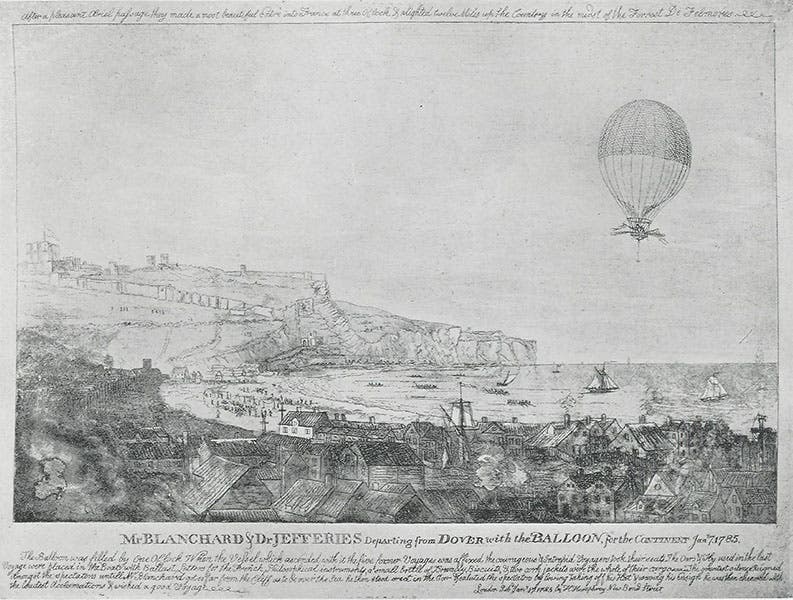

The departure of Blanchard’s hydrogen balloon on Jan. 7, 1785, in the first crossing of the English channel by aeronauts, engraving of Jan. 17. 1785, reproduced in The History of Aeronautics in Great Britain, from the Earliest Times to the Latter Half of the Nineteenth Century, by J. E. Hodgson, 1924 (Linda Hall Library)

This set the stage for Blanchard's goal all along, to balloon across the English Channel. Pilâtre de Rozier had the same idea; he was sitting on the other side of the channel with his hydrogen balloon, waiting for favorable winds to take him westward to Dover. Blanchard won the battle of the winds. He and Jeffries took off from Dover on Jan. 7, 1785 (fourth image). They almost ended up in the sea, as their bag of hydrogen was providing insufficient lift, and they threw nearly everything overboard, including most of their clothes, to maintain altitude. But the balloon for some reason recovered its buoyancy, and they made it to Calais and beyond, landing at Guines, to the great excitement of the local populace. Pilâtre was greatly disappointed, of course, that he was not the first, but he played the good sport and accompanied Blanchard and Jeffries to Paris, where they were greeted by the King and Blanchard received a small royal pension. Pilâtre got his chance five months later, on June 15, when the winds turned, and he and his balloon-mate took off from Calais, headed for Dover. Unfortunately, the hydrogen in his balloon caught fire just after reaching altitude, and the balloon plummeted to earth. Pilâtre was killed, the first victim of a ballooning accident. You can see several images of the fiery crash, fanciful though they are, at our post on Pilâtre de Rozier.

Blanchard avoided a similar fate, at least for another 23 years. He took his balloon anywhere that he could find a paying crowd. He even came to the United States, and on Jan. 9, 1793, he made the first American balloon ascent, lifting off from a prison yard in Philadelphia and setting down in New Jersey. Today is the anniversary of that flight. It is said that the ascent was observed by George Washington, who was U.S. President at the time, and by John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, who were waiting their turn (to be president). It is usually added that Blanchard carried a letter on his first U.S. flight, marking the advent of air mail, but if so, it must have been addressed "to whom it may concern," since no one knew where a launched balloon was going to end up.

Blanchard married Sophie Armant in 1804. When Jean-Pierre had a heart attack while aloft in 1808, and fell from his balloon, sustaining injuries that resulted in his death a year later, Sophie took up the ballooning profession, and she made a number of public ascents until July 6, 1819, when some fireworks that she unwisely deployed while aloft ignited her balloon, and she was ejected from the gondola and fell to her death. We wrote a post on Sophie some years ago.

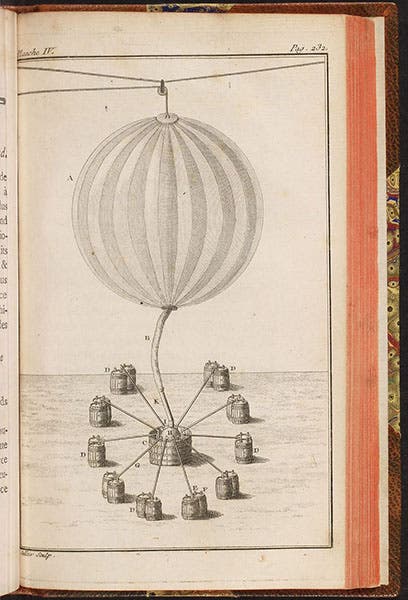

Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond wrote one of the first accounts of the origins of ballooning in 1783-84, and one of his engravings (sixth image) shows the apparatus invented by Messiers Vallet and Alban of Paris to generate hydrogen gas by immersing sheets of iron in barrels of sulfuric acid and collecting the gas produced in the (rather violent) reaction. They used 10 pairs of barrels, arranged in a circle around the balloon. According to Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, the apparatus was invented specifically to supply hydrogen for the balloon of Jean-Pierre Blanchard.

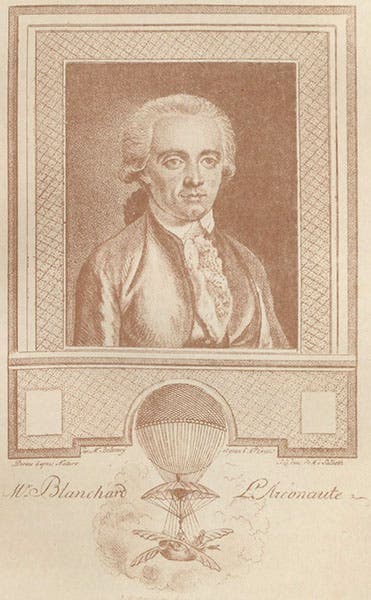

We have many other well-illustrated books on the origins of ballooning in our collections, most of them much more recent, including one of my favorites, The Montgolfier Brothers and the Invention of Aviation (1983), by Charles Coulston Gillispie. Today we have drawn three of our images from another favorite, The History of Aeronautics in Great Britain, from the Earliest Times to the Latter Half of the Nineteenth Century, by J. E. Hodgson (1924). This book, an oversize quarto, reproduces many original ephemeral engravings that are now impossible to find, and happily, it is now out of copyright. One of these provides a second portrait of Blanchard (seventh image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.