Scientist of the Day - Jean-Francois Pilâtre de Rozier

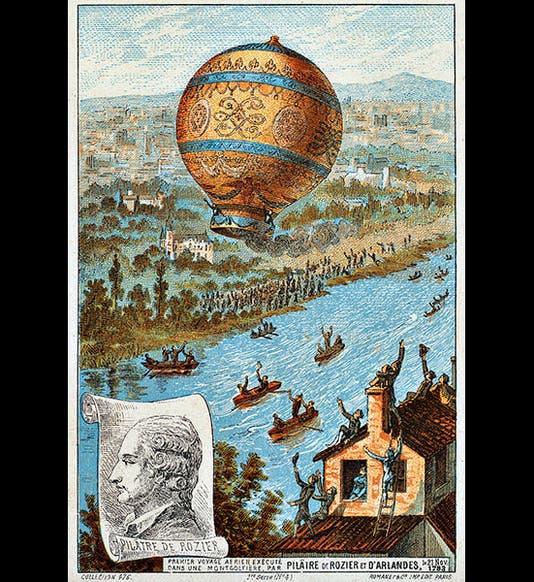

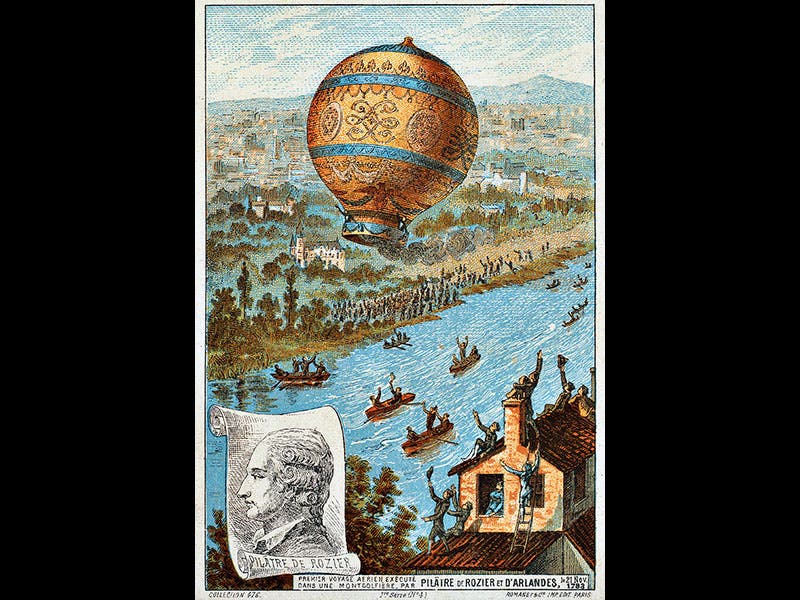

Jean-Francois Pilâtre de Rozier, a French chemist of sorts, was born Mar. 30, 1754. Pilâtre de Rozier was one of two passengers in the first manned balloon flight of Nov. 21, 1783. The hot-air balloon had been built by two brothers, Jacques and Etienne Montgolfier; Pilâtre de Rozier was the scientist on board and he shared the basket with a nobleman, the Marquis d'Arlandes. The take-off was rocky, as the balloon initially deflated and popped a few seams, but the balloon was repaired and successfully re-inflated, and soon ascended to an altitude of a thousand feet or so and moved along the Seine. Benjamin Franklin observed the flight from the terrace of his house in Paris, where an artist drew a sketch that would be the basis for a number of engravings, including the one above (second image). The balloon landed safely in a field after a 5.5 mile flight that took about half an hour. The aeronautical age had begun.

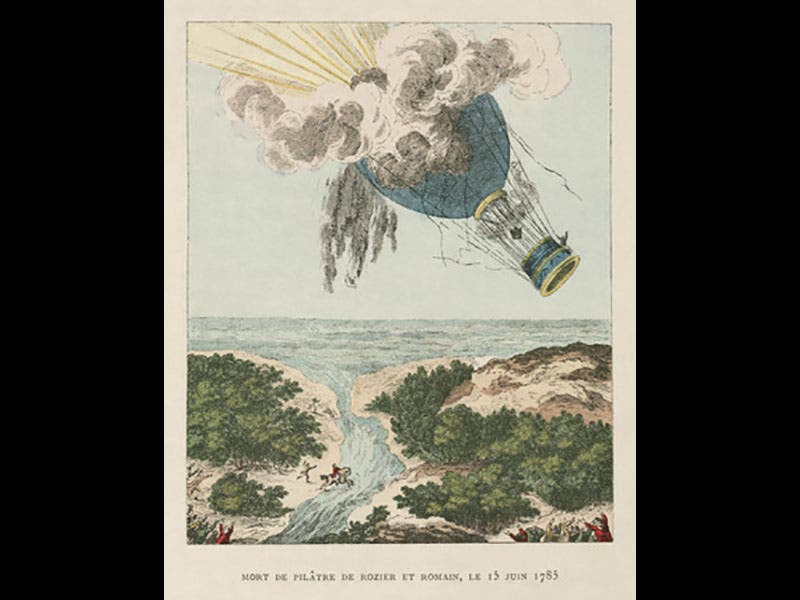

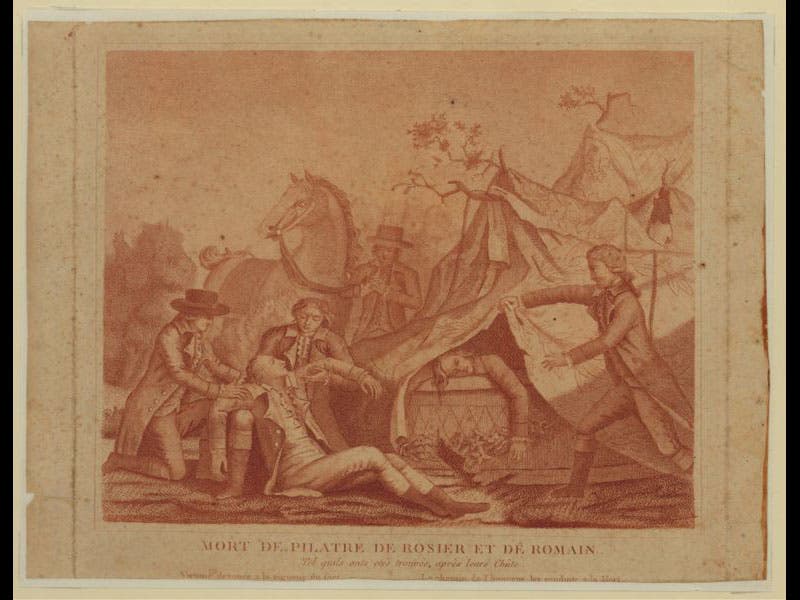

Pilâtre de Rozier did not live to see much of that age. He died in a balloon crash on June 15, 1785, attempting to be the first to fly across the English Channel from France. He was flying in a double balloon--the bottom bag containing hot air and the upper bag holding what was then called "inflammable air"--we would call in hydrogen. The balloon was safely launched, but something soon thereafter sparked the upper bag and it burst into flames. Without the lift provided by the hydrogen, the balloon and gondola crashed to Earth, killing both Pilâtre de Rozier and his companion. Several engravings were made of the disaster, although neither of them really shows us what the double-balloon looked like when aloft. One (third image) rather fancifully imagines the fiery explosion that preceded the crash; the other (fourth image) depicts the dead or dying passengers, with Pilâtre de Rozier on the left.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.