Scientist of the Day - Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois

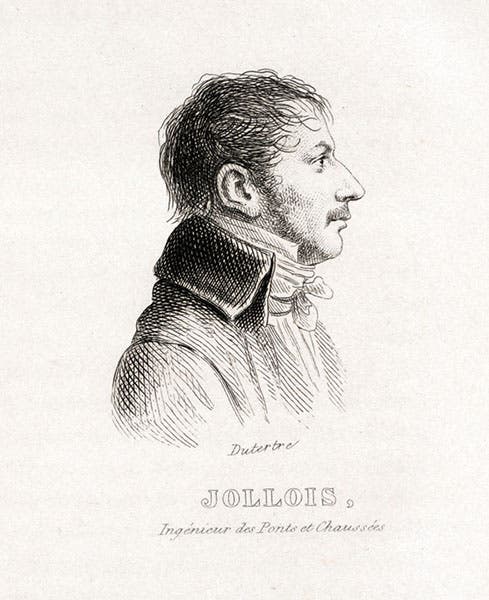

Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois, a French civil engineer, was born Jan. 4, 1776. He was in the very first class of the new Ecole Polytechnique, founded in 1794 to train engineers, and no sooner did Jollois graduate than he was tapped by senior scientists to join Napoleon on his scientific expedition to Egypt in 1798. Jollois was one of what is traditionally said to have been 151 savants – there may have been as many as 167 – who were picked to form a Commission of Arts and Sciences to go by ship to an unknown destination and there investigate the geography, natural history, and modern culture of this country yet to be announced. Jollois, like most of the invitees, accepted, and proceeded to make his way down to Toulon on the Mediterranean, where a flotilla of 400 ships was to be launched. The savants would be vastly outnumbered by the 54,000 soldiers and sailors, who did not think much of the presence of non-military personnel on a military operation.

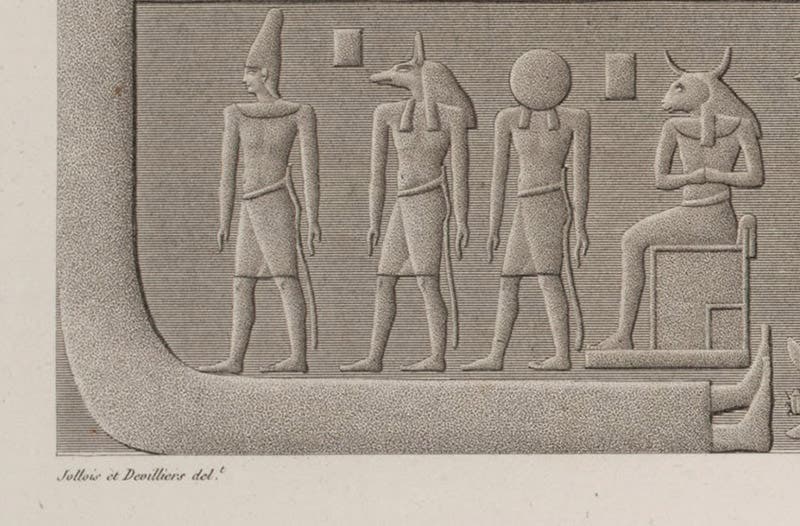

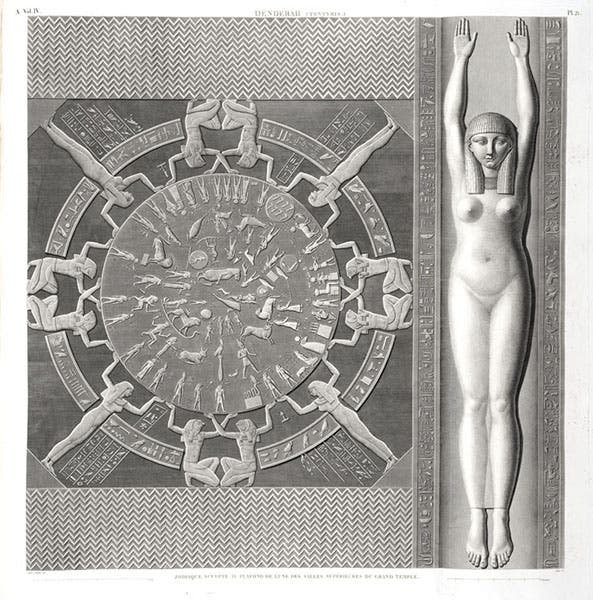

The focus of the invasion was revealed when they landed at Alexandria on July 1, 1798, and slowly made their way to Cairo, overcoming resistance by the armies of the mamelukes. Jollois spent his first few months surveying the remains of an ancient canal in the Sinai area, but then in the spring of 1799, he was assigned to accompany Pierre-Simon Girard, chief engineer, as he made his way to upper (southern) Egypt, following in the wake of military forces pursuing the mamelukes. The job of the young engineers was to survey the Nile and the irrigation systems in use. But when they reached a location near Dendera, everything changed, at least for Jollois. There he met the artist Vivant Denon, who had accompanied the first military invasion into upper Egypt, and who had discovered not only the ruins of a temple at Dendera, but a carved stone zodiac hidden in a small room on the top of the temple. Denon attempted a rough sketch, but he had no time, as his troops moved on. Jollois and a young friend, Devilliers du Tirage, visited Dendera and proceeded to measure and map the site and draw the ruins, including the zodiac, which was on a ceiling in the darkened room and very difficult to see, much less draw, with accuracy.

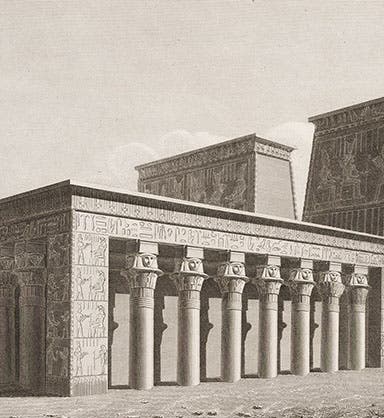

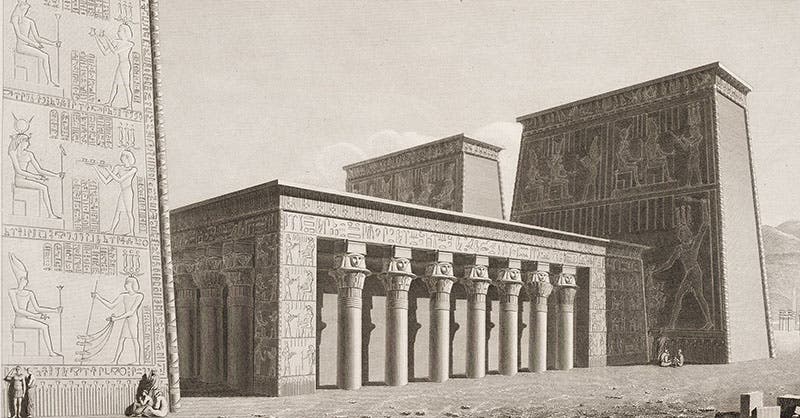

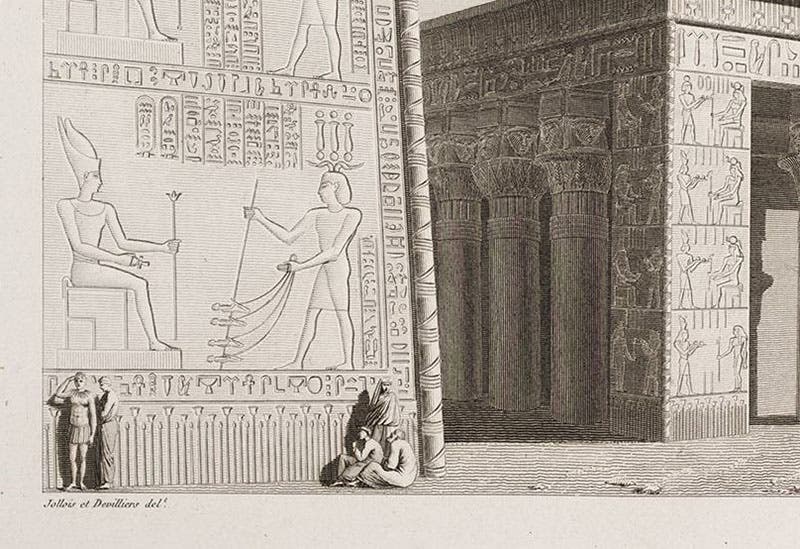

Girard was not pleased with his young charges wasting their time on antiquities, and forbade them to continue such activities, but they pursued them anyway when Girard was not around. As the contingent got to Esna, Edfu, and Kom Ombo, the ruins of more temples were mapped and drawn. After recording the sites as they were now, Jollois and Devilliers liked to image them as they had existed thousands of years ago, and they made many “vue perspectives”, as they called them, restorations on paper, peopling them with ancient Egyptians.

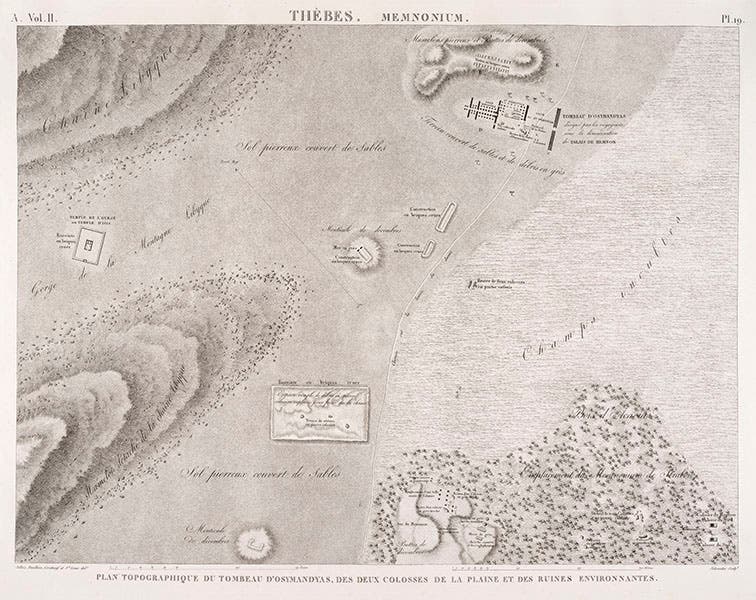

Girard’s contingent finally reached the island of Philae at the first cataracts of the Nile, and the engineers recorded the temples there (the ruins they drew are not longer where they observed them, since Philae was flooded by the rising waters behind the Aswan dam, and all the ruins were moved stone by stone to a substitute island above lake level). After Philae, they returned down the Nile to Thebes, which they had seen only briefly on the way up, and now they had time to map the vast region west of Thebes known as the Memnonium.

Jollois and Devilliers and the other young engineers returned to France in late 1801, as the French invasion army was conquered by the British and most of their collected artifacts were commandeered by the British, so that the Rosetta Stone, for example, was taken to the British Museum, not the Louvre. But Jollois and Devilliers were able to keep their drawings, and when the Description de l’Égypte, the beautifully illustrated account of the work of the savants in Egypt, began publication in 1809, many of the plans, elevations, and restorations by the two engineers were included as large engravings. We can tell who did what since each engraving was signed at lower left by the artists involved.

We include here a drawing of a restoration of the temple complex at Philae (first image), as well as a detail of the lower left, where you can see not only lounging imaginary priests, but the names of Jollois and Devilliers (sixth image). We also include a detail of a ground plan of the ruins at Dendera. The entire engraving is much larger than this, but at that scale, no details are visible, so we show just the part that includes the temple itself (third image).

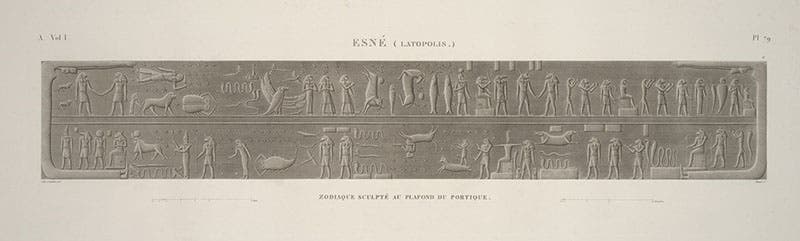

When the engineers were at Esna, they found a second zodiac, this one rectangular rather than circular, and they recorded it as best they could (fourth image). It must have taken many hours to draw and properly locate the constellation figures. The drawing is signed at lower left, “Jollois et Devilliers”; fifth image).

We have written a post on Devilliers du Terrage, and we showed there a detail of the Zodiac of Dendera, and a detail of the ground-plan of the Memnonium at Thebes. We thought for this occasion we would show the entire plates from which those details were taken. Here we see that the Zodiac at Dendera was flanked on the ceiling by the figure of Nut, the sky goddess (seventh image). And on the complete map of the Memnonium, we can better see its extent, including the temple of “Ozymandias” at top right, as well as the two colossal sitting statues of Memnon that jut out of the floodplain, here just a pair of tiny dots below the temple. You can see the two colossi as drawn by Denon in our post on Denon (second image there), while just below it is Denon’s cursory drawing of the Zodiac at Dendera (third image there).

This is our 17th post on one of Napoleon’s savants in Egypt. You can find an account of this monumental scholarly invasion in our exhibition catalog, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt (2006). Here is the page on Jollois and Devilliers, and another on Denon. If you would like more detail, I recommend Mirage: Napoleon’s Scientists and the Unveiling of Egypt, by Nina Burleigh (HarperCollins, 2007), and The Discovery of Egypt: Artists, Travellers and Scientists, by Fernand Beaucour et al. (Flammarion, 1990), which includes many color plates of the original drawings by the engineers used for the engravings, and still preserved in the Louvre or the Bibliothèque Nationale.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.