Scientist of the Day - Jean-Baptiste Lepère

Jean-Baptiste Lepère, a French architect, was born Dec. 1, 1761. Lepère was one of the 151 engineers, artists, scholars, and naturalists who were invited to accompany Napoleon and his army when they invaded Egypt in the summer of 1798. Lepère was 36 years old when they landed. I do not know what Lepère's official duties were during the three years he was in Egypt, but if one were to make a surmise after leafing through the 837 engravings in the thirteen plate volumes of the expedition’s official narrative, Description de l’Égypte (1809-1828), one might well conclude that Lepère was in Egypt for the sole purpose of viewing the ruins at Philae, Karnak, Edfu, and Dendera, restoring them in his mind's eye to their original grandeur, and then committing those restorations to paper for the engravers. Many of the young topographical engineers liked to do imaginative restorations of the temples and tombs they encountered, and we have profiled one of them, Edouard Devilliers du Terrage, but Lepère was by far the most successful at this enterprise, because he did most of the "wow" engravings – the ones that make visitors to our History of Science Collection gasp when you open up one of the super-sized Antiquites folios to a Lepère plate. Part of the reason for the impact of the Lepère engravings is that they tend to be hand-colored, but they were hand-colored because the editor, Edme Jomard, chose them for hand-coloring, because they were such mind-blowing engravings in the first place.

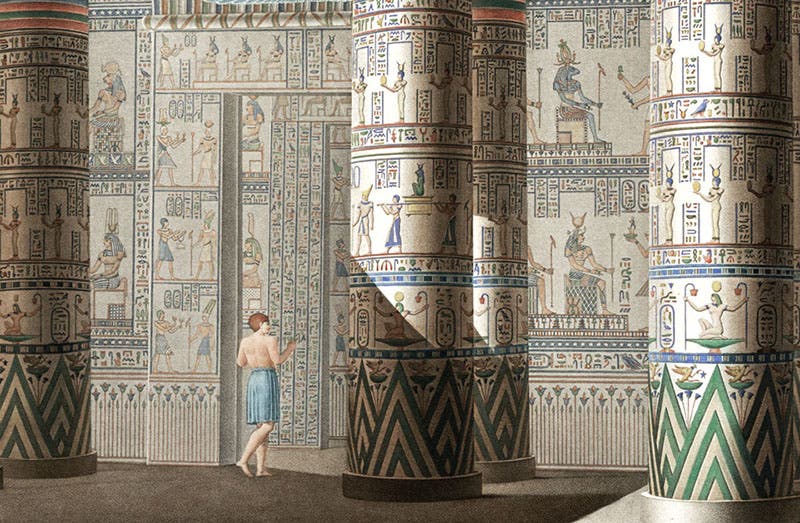

Our first image is a detail of the third – both show the interior of the Hypostyle Hall at the grand temple at Philae, 500 miles up the Nile from Cairo. In the detail, you can see that Lepère peopled his restorations with the figures of ancient Egyptians. In the full view, you might be able to read the beginning of the caption: “Vue perspective…” This was the phrase used by editor Jomard throughout the Description to advise that an image was a restoration. We wrote a post on Jomard just last week, where you can learn more about the publication of the Description de l’Égypte, if you are interested, and see another “Vue perspective,” drawn by Jomard himself.

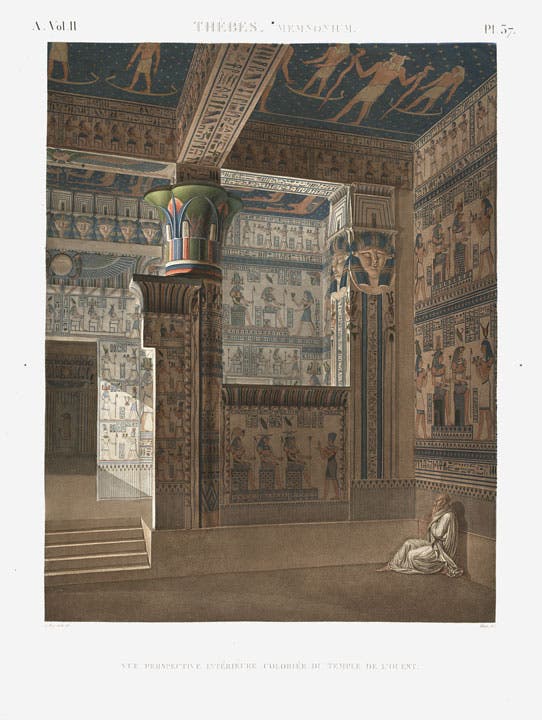

A second colored engraving shows the interior of the Temple of Hathor at Thebes, as restored by Lepère, and peopled with a lone priest (fourth image). In a detail of the ceiling, you get some idea of the richness and splendor of these engravings (fifth image). We used a different detail of Lepère’s engraving of the Hypostyle Hall at Philae for the front cover of the catalog for an exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt (2006), and a detail of the Temple of Hathor for the rear cover. The print run of that catalog has now, alas, been exhausted, although you can find the engraving of the hypostyle hall at Philae on the home page of the online version of the catalog.

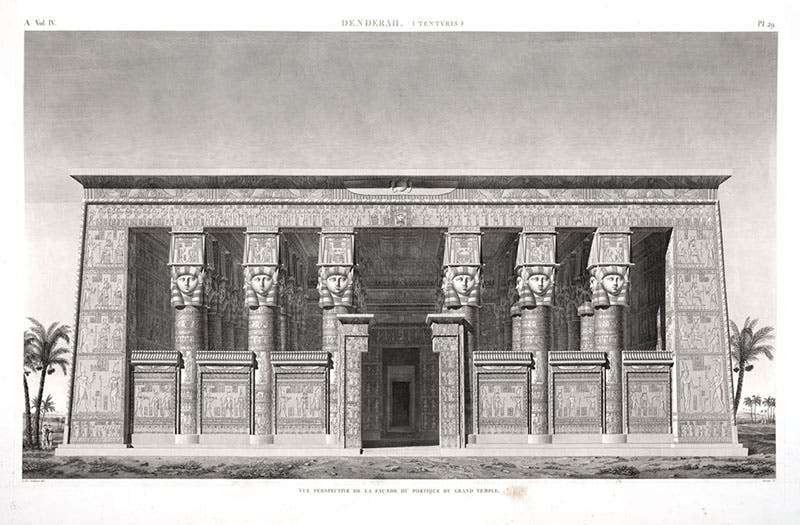

Lepère’s drawings did not have to be colored to be arresting. His “perspective view” of the temple at Dendera, is wonderfully done (sixth image). This depicts the building where the famous Zodiac of Dendera was found, in a small room up on the roof, which you can read about in the online exhibition catalog. Lepère also made a separate drawing of one of the columns, with its Hathor-headed capitals, which became the basis for yet another hand-colored engraving. We show here just a detail of that engraving, zooming in on the capital (seventh image).

We know what Lepère looked like at the time of the Egyptian expedition because one of the artists, Andre Dutertre, took it upon himself to sketch every one of the engineers and scholars, and some of the military officers, and these were later published in a history of the expedition (1830-36). We use Dutertre’s sketch of Lepère as our second image.

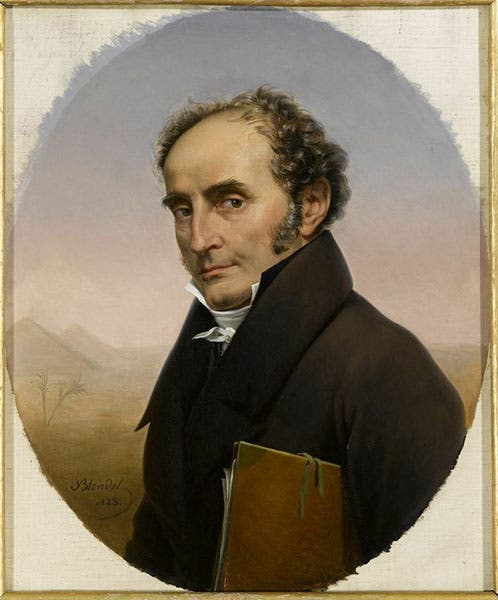

Lepère lived another 43 years after returning to France from Egypt, practicing architecture, but this part of his life doesn’t seem to have made much of a historical dent – at least, I could find out little about his architectural career. But I did discover a wonderful portrait of Lepère, now in the Louvre, painted by Merry-Joseph Blondel in 1823, when Lepère was 61, looking remarkably fit (eighth image). He is framed against the pyramids at Giza.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.