Scientist of the Day - Jean-Baptiste Croizet

Jean-Baptiste Croizet, a French geologist and paleontologist, was born in Coumon, a town near Clermont in the Auvergne region of central France. He received much of his education at a seminary in Montferrand, also near Clermont. He was apparently a bright young man, so he was sent to a nearby school to be educated in the sciences, before he settled down as an abbé in Neschers, another commune in the greater Clermont area. It is not clear how he became interested in geology and fossils, but he grew up in one of the geologically most interesting regions in all of France. The Auvergne region is studded with extinct volcanoes, lava flows, and basalt formations, which had only recently (1771) been recognized as such by Nicolas Desmarest. The highest volcanic plug in the area is the Puy de Dôme, which Pascal made famous when his brother-in-law Florin Périer in 1648 carried a Torricellian tube to the top of the mountain to demonstrate that the atmosphere at the top has less weight than down in Clermont.

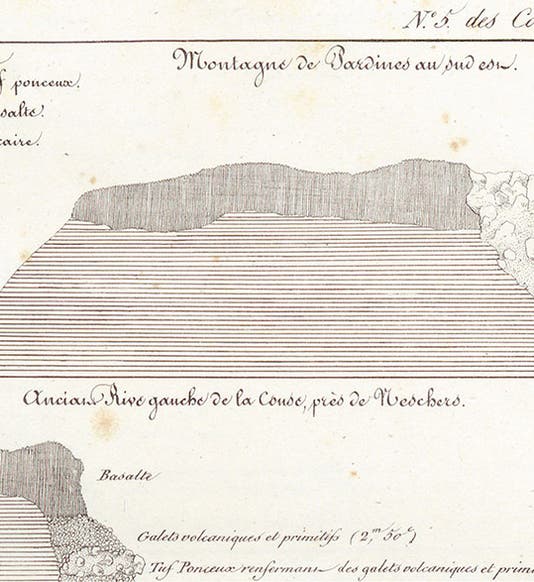

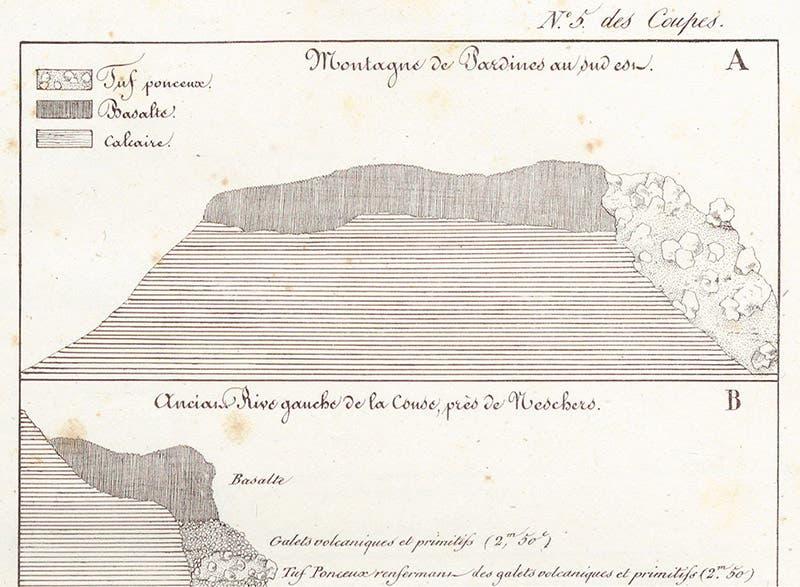

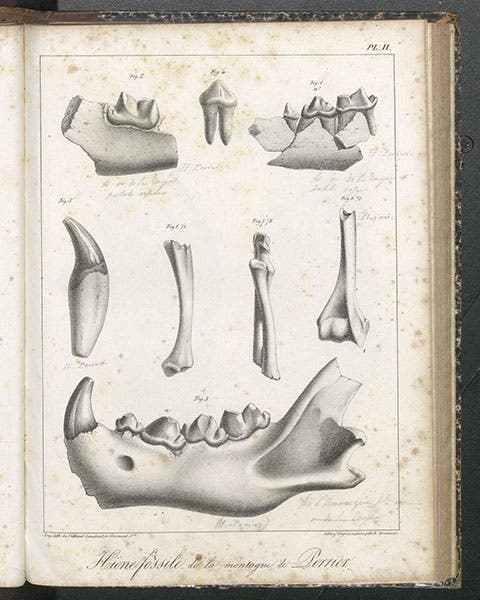

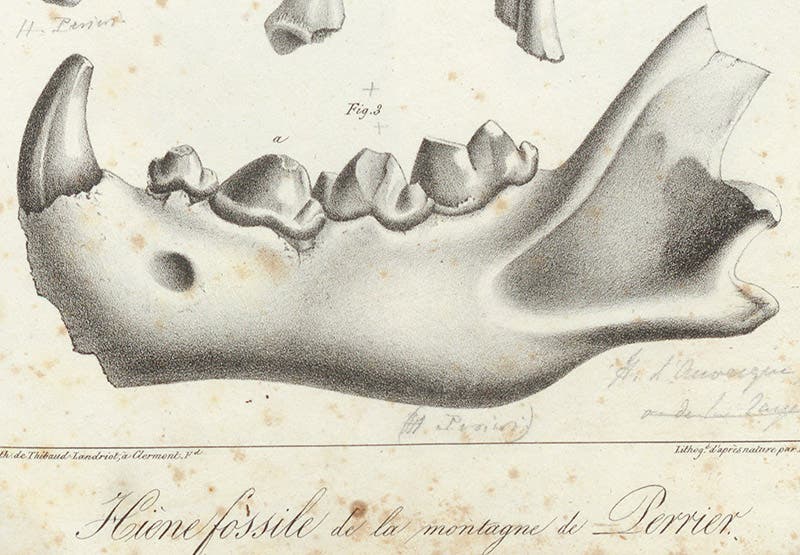

Sometime around 1824, Croizet and a friend, Antoine-Claude Gabriel Jobert, began to examine the area around Clermont, mapping the lava flows as Desmarest had before them, and the outcroppings of columnar basalt that seemed to be everywhere, and which, Desmarest had argued, emerged in a molten state from then-active volcanoes before cooling into distinctive prismatic shapes (first image). They also became aware of fossils that had recently been found near Perrier, another commune south-southeast of Clermont. There were remains of hyenas, hippopotami, rhinos, giant deer, and many other animals that could no longer be found in the area. The prevailing view of such fossil deposits at the time was that of Georges Cuvier, who called such fauna diluvial, meaning they predated one or more cataclysmic floods that removed pre-existing fauna, allowing it to be replaced by modern fauna. William Buckland in England shared those views, having found hyena and bear fossils in caves in England that he dated to the diluvial period.

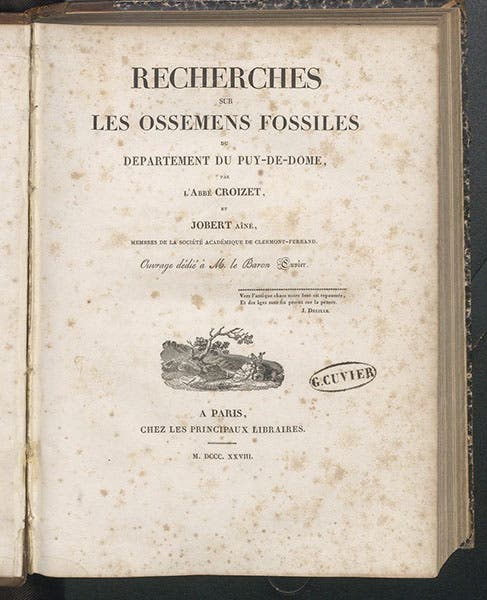

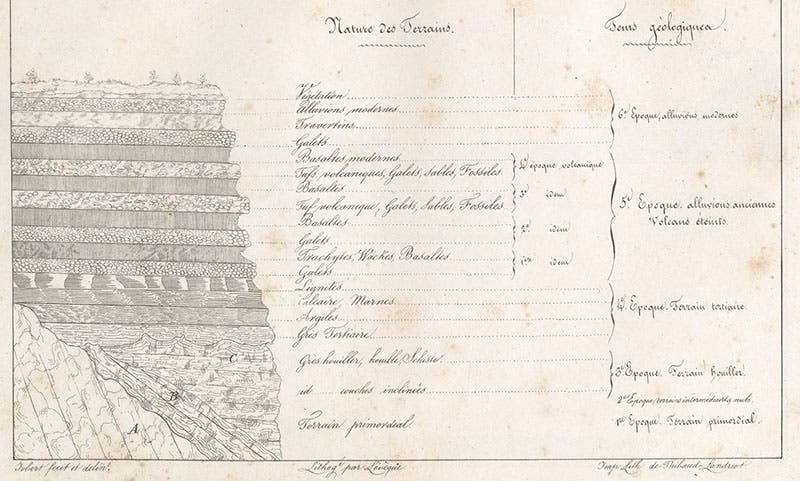

Croizet and Jobert sent specimens to Cuvier in Paris, who was quite impressed, although he still saw the fossils as diluvial. Croizet and Jobert were not so sure. They found no geological evidence of a cataclysmic flood in the Puy de Dôme area, and considerable evidence suggesting that the lava flows and erosion of valleys had been slow and continuous over long periods of time, and that the extinct animals died out gradually, not all at once in some geological revolution. Interestingly, an Englishman, George Poulet Scrope, was touring and mapping Auvergne at the same time as Croizet and Jobert, and he returned home to write a book, Memoir on the Geology of Central France (1827), with a gorgeous atlas containing multi-folded, hand-colored engravings of the formations of the Auvergne (you can see many of these at our post on Scrope), and he came to the same conclusion, that only time and ordinary geological forces had been needed to forge the elaborate formations of the Auvergne. But Scrope did not consider any fossil evidence. So when Croizet and Jobert published their own book the next year, Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles du Département du Puy-de-Dôme, offering fossil evidence for the slow, steady nature of geological process, they were going beyond, and indeed against, Cuvier and Buckland, and setting the stage for Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology (1830-33), which argued that one can explain all of geology using only present-day forces acting over long periods of time – revolutions and cataclysms are not necessary.

Geological section showing idealized superposition of formations in the Département du Puy-de-Dôme, detail of larger lithographed plate, Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles du Département du Puy-de-Dôme, by Jean-Baptiste Croizet and Antoine-Claude Gabriel Jobert, plate 1, 1828 (Linda Hall Library)

We have a copy of Croizet's book in our library, and if you look at the title page (third image), you will see there the stamp of Cuvier – this was the copy he had in his Library, probably a gift from Croizet and Jobert. It is a magnificent book, with many plates showing geological sections, basalt outcroppings, and the fossils. All of the plates are lithographs, which was a new technique for scientific illustration, and uniquely suited for depicting fossils, as you can see in our detail of the plate showing a hyena jaw (eighth image).

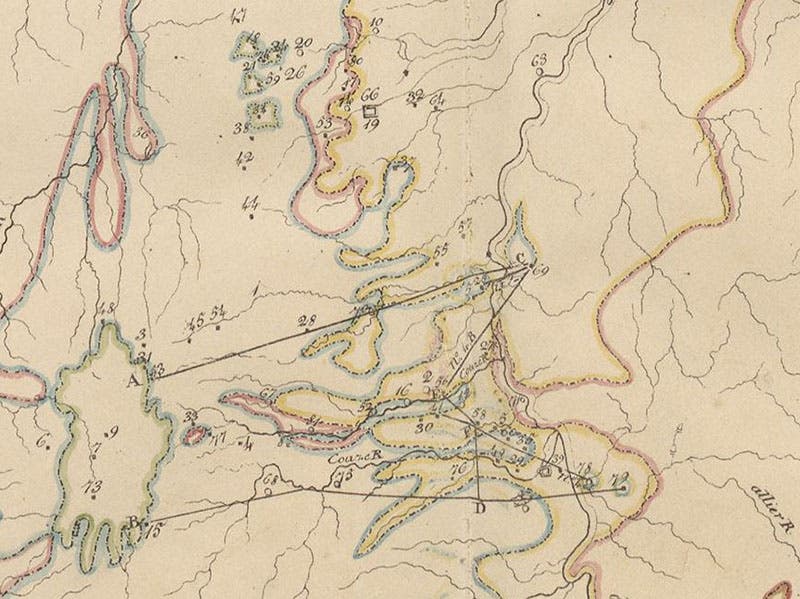

The finest illustration in the book is a lithographed map of the Department of Puy de Dôme. I have never seen it reproduced – indeed, I did not even know of its existence until I unexpectedly ran across it while preparing this essay It identifies over 80 features by numbers tied to a key on either side, so that one can locate not just the Puy de Dôme, but Pardines and Perrier, where the fossils were found. We show both the complete map and a detail (sixth and seventh images).

![Hydrographic map of the Auvergne region, with volcanoes identified, and location of sections indicated, folding hand-colored lithograph, in Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles du Département du Puy-de-Dôme, by Jean-Baptiste Croizet and Antoine-Claude Gabriel Jobert, plate [0], 1828 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/2e701920-c754-4476-b921-527d8d1f337c/croizet6.jpg?w=800&h=520&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Hydrographic map of the Auvergne region, with volcanoes identified, and location of sections indicated, folding hand-colored lithograph, in Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles du Département du Puy-de-Dôme, by Jean-Baptiste Croizet and Antoine-Claude Gabriel Jobert, plate [0], 1828 (Linda Hall Library)

Croizet achieved a certain eminence in natural history circles in Clermont, and published quite a few more books, but less ambitious than the Recherches. At any rate, we do not have any of them except the Recherches. But while Croizet has received his due, I worry about Jobert. He was the artist of the two, and he did all the drawings for the plates in Croizet’s book, including the map. But he is a totally unknown figure, even in France. He surely deserves improved billing.

Finally, I would l like to acknowledge the valued help provided by the most magisterial history of geology book ever written, Martin Rudwick’s Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform (2008). It is not for the faint of heart, or the scant of lap, with its 614 pages printed on heavy coated paper, but there is nothing else like it in geological literature in terms of scope, accuracy, and insight, except perhaps for its predecessor, Rudwick’s Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (2005). I could not write this column without them both.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.