Scientist of the Day - Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, a French politician and financial advisor to the King, was born Aug. 29, 1619. With the death of Cardinal Mazarin in 1661, Colbert became Louis XIV's most trusted adviser and eventually his Minister of Finances, a position he held until his death in 1683. He merits inclusion as a Scientist of the Day because, in December of 1666, he founded the Academie Royale des Sciences, the world’s second oldest, still flourishing scientific society, outranked only by the Royal Society of London, chartered in 1662.

Paris had seen the rise of several scientific academies in the 1650s and early 1660s, such as the Montmor Academy, which was formally organized in 1658, or the Thevenot Academy, founded in 1662. These were groups supported by private patrons, but they included many of the ablest scientists in France. They seem to have been inspired by the group that met in the cell of Marin Mersenne in Paris in the 1640s and included René Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Giles de Roberval, and Pierre Gassendi. This group continued to meet after Mersenne’s death in 1648 and eventually morphed into the Montmor Academy. The Academy closed in 1664, and apparently some of its members gave Colbert the idea for a national academy, and a royal one, supported by the King. Louis XIV agreed to the proposal, and Colbert then had to figure out whom to include as his first academicians. He invited Christian Huygens to come down from the Netherlands to be one of the academy mathematicians, rather a slap in the face to the many mathematicians in Paris, but then he also invited some local talent, such as Jean Picard, astronomer and geodesist, and Roberval, and Adrien Auzout, another astronomer and an alumnus of Montmor's academy. Soon he added a good friend, Claude Perrault, an architect, and another friend, his personal physician, Samuel Cottereau du Clos. And then Colbert reached out again to foreign lands for two more distinguished scientists, the astronomers Giovanni Domenico Cassini of Bologna, and Ole Römer from Copenhagen; both were asked to come to Paris to help design an astronomical observatory.

Unlike the Royal Society, which had scores of fellows, the Paris Academy had only 7 academicians at first, and the number never got much above 16. There were other differences – the fellows of the Royal Society had to pay dues for the privilege of belonging; the Paris academicians were paid a stipend from the Royal coffers, and their expenses in the form of laboratory materials were covered as well. The Royal Society had no permanent meeting place at first; the Paris Academy met in rooms in the King’s Library, or at the Jardin du Roi (the King’s Garden), or at Versailles.

However, the members of the Paris Academy also wore a yoke: they were expected to pursue matters that served the crown, not their own interests. Members of the Royal Society had no constraints – if someone wanted to study why plums are blue, or wished to bring a two-headed calf to a meeting, that was perfectly acceptable. The French academicians were told to pursue such matters as constructing an accurate map of France, or solving the problem of determining longitude at sea, or enlarging and organizing the King’s Garden and Menagerie. Those were important problems, worthy of scientific attention. But they were not pursuits that the academicians themselves selected.

Another limitation imposed on the academicians was secrecy, a problem that always seems to arise when the state gets involved in scientific matters. In the heady days of the early 1660s, everyone knew what everyone else was doing. Provincial scientists would come to Paris to learn about the hot topics of study, would get all excited, and return home to inform and inspire their colleagues. After 1666, such traffic ceased, for there was nothing to learn in Paris anymore. No one was talking. Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society in London, who had been so excited to hear about plans for a French Royal Society, was baffled when no one would even tell him who had been invited to join, much less what they were doing. Unlike the Royal Society of London, which began publishing its Philosophical Transactions in 1665, the Paris Academy had no journal to tell the world about their activities, nor would Colbert have ever permitted such revelations.

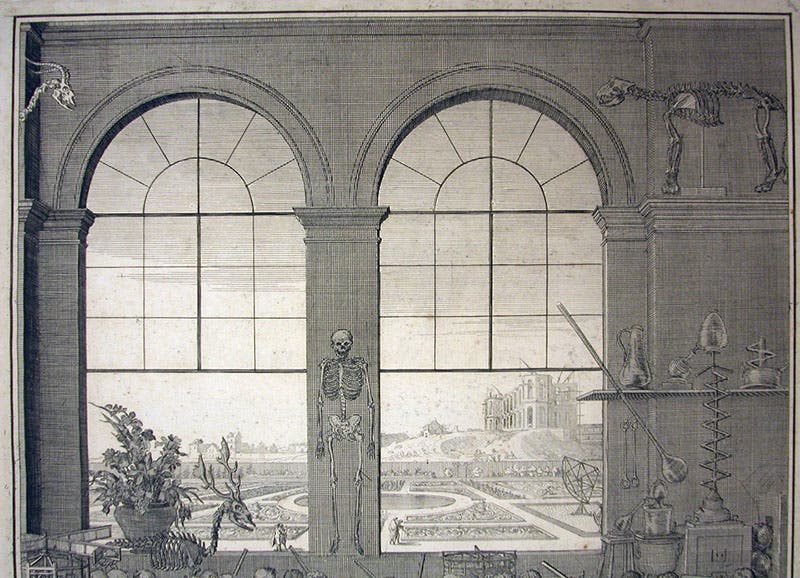

Louis XIV, happy at first to have his own network of scientific advisors, soon lost interest in what his academicians were doing, and left matters to Colbert. When the Academy published its first book, Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire naturelle des animaux (1671), by Perrault, they included a frontispiece by their artist, Sebastien Le Clerc, which depicted Louis XIV and Colbert visiting an Academy meeting (second image). It is a glorious scene, but entirely fabricated. Louis did not visit the academy until 1681 (to witness the dissection of an elephant), and the observatory, which you can see through the windows ot the meeting room (fourth image), cannot in fact be seen from any of the places where the academy convened. But we include a close-up detail of the central group anyway (third image), because it provides portraits (which were real) of Louis, wearing the hat, and Colbert, at the far right. That is Perrault staring out at the viewer between them.

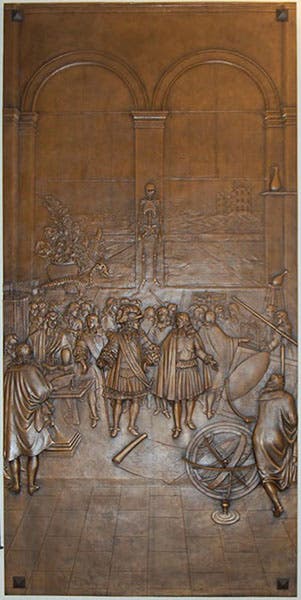

Louis XIV and Jean- Baptiste Colbert visiting the Royal Academy of Sciences, bronze wall panel modelled on Le Clerc’s frontispiece of 1671 (second image), by Bruno Bearzi, Linda Hall Library auditorium (Linda Hall Library)

Perhaps Colbert’s greatest achievement relative to the Academy was getting the Observatory built and supplied with instruments. Although he invited Cassini and Roemer to help with the design, he began without them, asking Perrault (architect of the east wing of the Louvre) to design the building, even though Perrault was not an astronomer. So Cassini had to do a lot of re-design when he got there, and the location was not really convenient. But many famous French astronomers would call in home over the next three and a half centuries. And it is still there, now primarily a library and museum, and worth a visit on your next trip to Paris. The meridian of Paris runs right through its middle.

Colbert has been in the news of late because of his supposed role in the writing of the Code Noir, the guide to proper practices for French colonial slaveholders that was issued to satisfy mandates by Louis XIV in 1685. Colbert’s statue in Paris (sixth image) has been defaced several times by protesters. But Colbert had come down with painful abdominal problems in 1681, and would die of kidney stones in 1683, and it is doubtful that he had anything to do with the Code Noir, except to pass along Louis’s demands to colonial administrators.

Colbert was a warden of the Church of Saint-Eustache in Paris, a wonderful old cathedral whose exterior style has been labelled “Flamboyant Gothic,” and Colbert bought a chapel there. After his death, an elaborate funerary monument was designed by Antoine Coysevox and Jean-Baptist Ruby and put in place in 1687. It includes another memorial statue of Colbert (seventh image)

Our library has six historical bronze wall panels that were commissioned for the building exterior in 1964 and installed in 1967, fashioned by the eminent Florentine foundryman Bruno Bearzi. You can see all 6 at our post on Bearzi. One of them showed the famous if fictitious visit of Louis XIV and Colbert to the Academie des Sciences, from the 1671 frontispiece. This panel had to be moved inside when a new wing was added, and it was refinished for some reason, removing the beautiful verdigris patina of the other exterior panels. Nevertheless, you can see it much more easily than the ones outside, as it now hangs on the front wall of our auditorium (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.