Scientist of the Day - Jean-Baptiste Charcot

Jean-Baptiste Charcot, a French polar explorer and physician, was born July 15, 1867. His father, Jean Charcot, was a famous physician in his own right. Charcot early on decided to become a polar explorer, originally intending to sail into Arctic regions, and diverting to the Antarctic region when the Swedish expedition led by Otto Nordenskjöld went missing in 1903 (but then was found later that year). The French had been prominent in exploring the south polar seas in the late 1830s, when Jules-César Dumont d’Urville had taken the Astrolabe and the Zélée as far south as they could go and had sighted (but did not land on) the Antarctic continent. But since that time, the French had yielded the field to the English, the Swedes, and even the Belgians. It was Charcot’s goal to establish a French presence on the southern continent, on which no Frenchman had yet set foot.

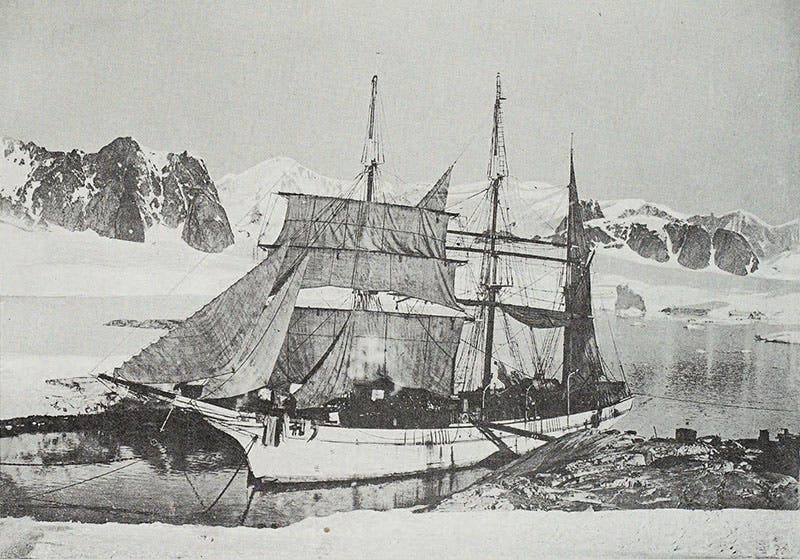

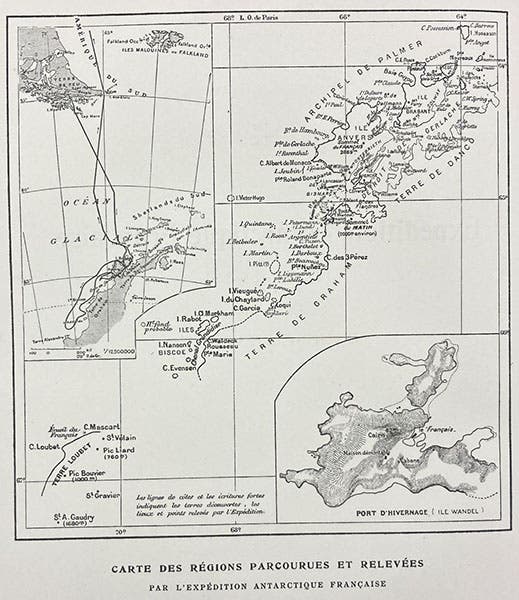

The first French Antarctic expedition, put together and led by Charcot, travelled south on the ship Le Français in 1903 and returned in 1905, overwintering in 1904. Their base away from home was Argentina, from which they descended to explore the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, the long finger of land that sticks up toward Tierra del Fuego, and which had been subdivided into Palmer Land at the tip and Graham Land at the base. There are dozens of islands and island chains along the west coast which had never been visited, much less mapped, and this is where Charcot pointed his ship.

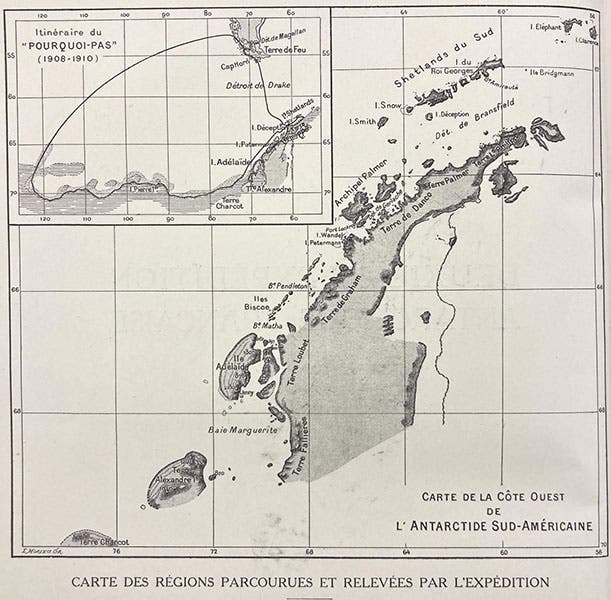

Map and enlarged map of itinerary of the first French expedition to Antarctica, 1903-05, which explored the islands off the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula; the southern tip of South America is at the top; frontispiece to vol. 10 of Expédition antarctique française (1903-1905), by Jean-Baptiste Charcot, 18 vol., 1906-09 (Linda Hall Library)

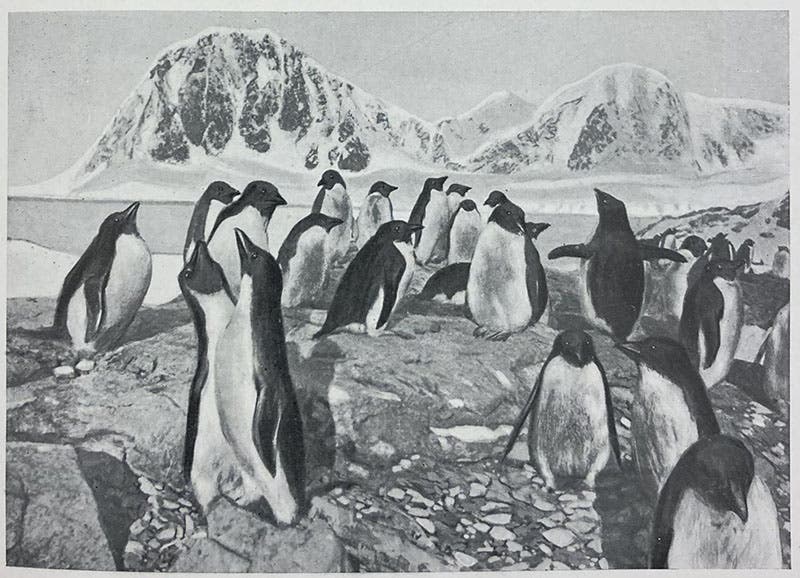

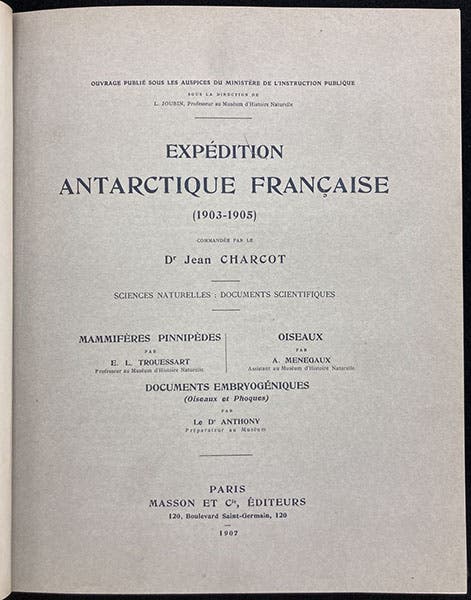

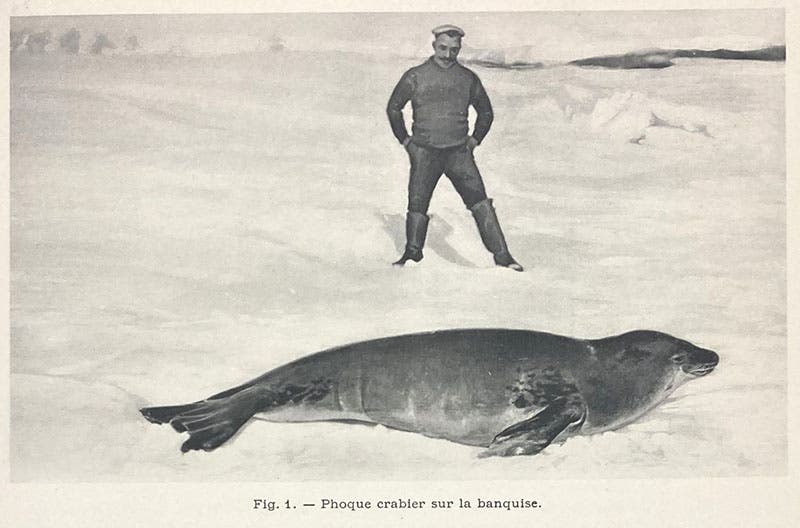

The expedition was successful, in an undramatic way, as a thousand miles of unexplored coastline was mapped, and a variety of marine life was studied and collected by the half-dozen scientists on board. When they returned in 1905, Charcot was greeted as a maritime hero, and he promptly took on the task of editing the scientific results for publication. The Expédition antarctique française (1903-1905) was published in 18 volumes between 1906 and 1909 (with one late volume in 1924), which sounds like a lot, and is, but not as much as you might imagine, as many of the volumes, such as one on hydroids, are only a few pages long. We have the complete set in our collections. The volume on mammals and birds is the thickest, with many photographs of seals and penguins, of which we show several here (first and fifth images). The man with the basking crab-eating seal almost looks like a young Charcot, without the goatee, but I think the sailor’s cap probably argues against that.

Charcot had spent a large portion of his own inheritance in fitting out the Français, but he got financial help from the government when he wanted to organize a return expedition. He had a new ship built, the Pourquois-Pas? (Why not?), which was actually the fourth by that name, although the “IV” is usually omitted (sixth image). Charcot chose the same area to explore, except that they went further south and then west along the Antarctic coast, as you can see in the map (seventh image). The expedition left in 1908 and returned in 1910, without mishap, having charted another 1200 miles of previously unexplored coastline. Once again, Charcot sat down to edit the proceedings, which this time amounted to 24 volumes, published between 1911 and 1917, with World War I slowing things down a bit, but not much. We have this complete set in our collections as well. Charcot wrote a more popular book, Le Pourquoi-Pas? dans l’Antarctique (1910), which included the photograph of his ship, but we do not have this account in our library.

Charcot retired from the Antarctic, but not from the Pourquoi-Pas?; it would have been better if he had, because he was onboard when the Pourquoi-Pas? was wrecked near Iceland in 1936, and only one soul survived, and that was not Charcot, although the ship was recovered and is, I believe, on display in a French maritime museum. Charcot was buried with great ceremony in Montmartre Cemetery in Paris.

Charcot’s two Antarctic expeditions are usually eclipsed by the more dramatic, and in some cases calamitous, adventures of Ernest Shackleton, Road Amundsen, and Robert Falcon Scott, and Charcot is often not even mentioned in accounts of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration. However, each of Charcot’s expeditions did merit a chapter in Let Heroes Speak: Antarctic Explorers, 1772-1972, by Michael H. Rosove (2000), a book I own and can recommend. The “1772” in the title refers to the second voyage of James Cook, which we discussed just last week.

Each of the 24 paper covers of the proceedings of the second French Antarctic expedition has a small logo of a ship, presumably the Pourquoi-Pas?, with two penguins, in the upper right corner. I don’t know the story behind it, but with its simple lines, it appeals to me, and I reproduce it here, greatly enlarged, so you can appreciate it as well (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.