Scientist of the Day - Jean-Antoine Chaptal

Jean-Antoine-Claude Chaptal, a French chemist, industrialist, and government minister, was born June 4, 1756, in southwestern France. Thanks to a wealthy uncle, he received a medical degree from Montpellier and was able to study chemistry in Paris. He returned to Montpellier around 1780 and quickly established a chemical industry there, manufacturing salts, gunpower, and commercial acids. I have sometimes wondered if the hydrogen used by Jacques-Alexandre Charles in his first balloon flights of 1783 was generated by sulfuric acid provided by the Chaptal chemical works.

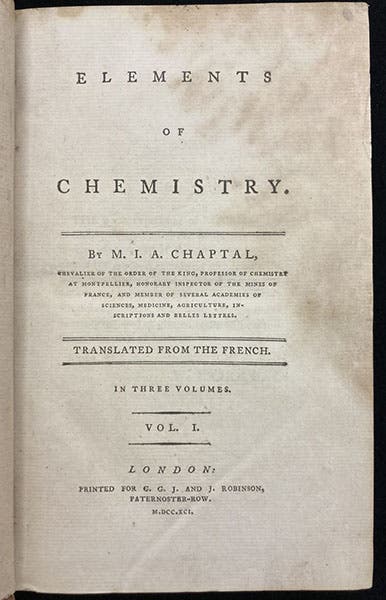

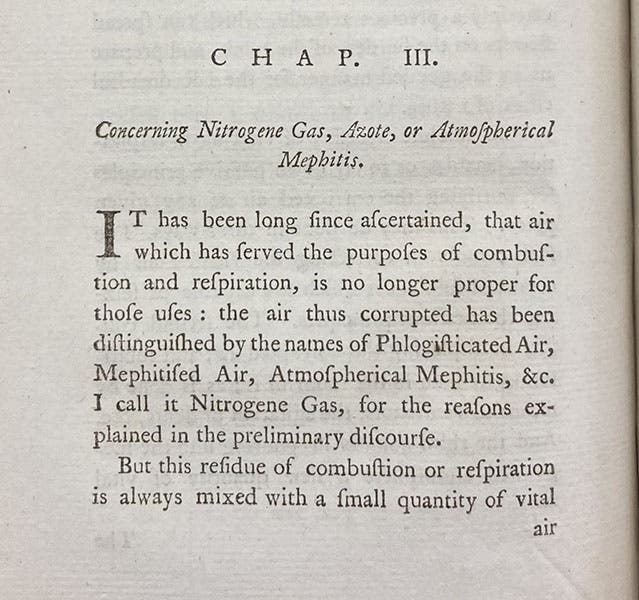

There was a chemical revolution underway in Paris, and Chaptal got to know Antoine Lavoisier, Claude-Louis Berthollet, Antoine Fourcroy, Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, and the others involved, and shared their enthusiasm for reform. Chaptal's successful career of the 1780s was interrupted by the French Revolution of 1789, which cost him most of his fortune, but he was able to physically survive where others, such as Lavoisier, were not so lucky, perhaps because his mastery of chemical industry, especially gunpowder manufacture, was indispensable in times of war, a state in which France found itself from 1789 to 1815. Chaptal did manage to publish, in 1790, before the Revolution was too far advanced, his Elemens de chemie (1790), which was immediately translated into English by William Nicholson. We have the English translation (1791), and we show you the page on which Chaptal first introduces the term nitrogen, for what Lavoisier called azote, and Priestley called phlogisticated air (third image).

In 1799, Napoleon declared himself First Consul and proceeded to reorganize the government. Napoleon, especially since the expedition to Egypt of 1798, was favorably disposed toward scientists, and he chose Pierre-Simon Laplace as his first Minister of the Interior. Brilliant mathematician though he was, Laplace was a dismal administrator and had to be replaced almost immediately. Napoleon's younger brother, his second option, was even worse, so Napoleon, for his third choice, picked Chaptal, and here he lucked out. Chaptal was a superb organizer and proceeded to reform the entire industrial superstructure of France. He established industrial fairs and competitions to encourage invention and innovation, and he established a new association, the Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale, to organize industrial exhibitions and competitions (the Lumiere brothers, nearly a century later, in 1895, presented their first moving pictures to a gathering of this society.) In one of his less appreciated acts, which has nothing to do with science but seems worth admiring, Chaptal, in 1801 established by decree ("Chaptal's decree”), 15 provincial art museums, in places like Lyon, Caen, Rouen, and Nancy, in order to redistribute the wealth of art in Paris, both legitimately acquired and those taken as spoils of war. France, at one fell Chaptalian swoop, had an art museum network, one which is still in place.

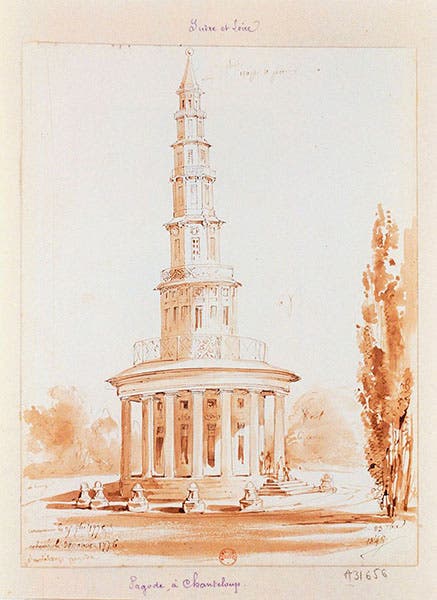

Chaptal resigned as Minister in 1804 to return to scientific pursuits, much to the disappointment of Napoleon. Chaptal had purchased an estate in 1802, the Château de Chanteloup, near Amboise, where Leonardo da Vinci had lived his last few years, had died, and was buried. Somewhere along the line, Napoleon made Chaptal a count, for he is commonly referred to after 1810 as the comte de Chanteloup. The Château de Chanteloup was not quite as extensive as the Château de Amboise, but it had one thing Amboise did not – a large pagoda, built in 1777, that still stands (fourth image). Chaptal turned the management of his factories over to his son, and this worked well for 20 years, until his son over-extended himself and was financially ruined, so that Jean-Antoine, in 1822, had to sell his estate.

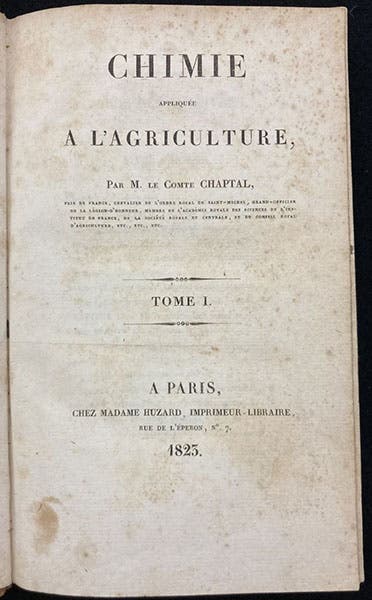

But before that, Chaptal practiced scientific farming at Chanteloup, raised Merino sheep and sugar beets, and wrote books in which he virtually founded the fields of applied chemistry, industrial chemistry, and chemical agriculture. We have two of those works in our collections, his La Chimie appliquée aux arts (1806) and Chimie appliqueģe a l'agriculture (1823; fifth image).

As we have mentioned and illustrated from time to time in this series, the names of 72 French scientists, all male (we pointed that out in our post on Sophie Germain), are engraved on a frieze on the Eiffel Tower, just below the first balcony. Chaptal was one of those so memorialized. If you look at the tower from the northwest, from the Trocadéro (sixth image), Chaptal is at the far right of the 18 names on this side, as we see in a detail that begins with Lavoisier and ends with Chaptal (seventh image).

Chaptal died on July 30, 1832, and was laid to rest in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris; the class of 1832 at Père Lachaise also included Georges Cuvier and Jean-François Champollion, decipherer of hieroglyphics. Since I could find no good photo of Chaptal’s monument online, I show instead a second portrait, with which I came face to face just a month ago, when I visited, for the first time, the splendid Cleveland Museum of Art. The oil portrait by Antoine-Jean Gros, was painted in 1824.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.