Scientist of the Day - Jan Oort

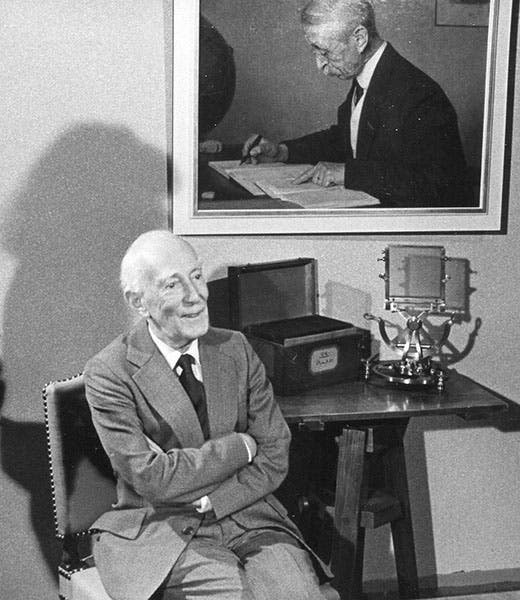

Jan Oort, a Dutch astronomer, died on Nov. 5, 1992, at the age of 92, having been born in the last year of the 19th century, Apr. 28, 1900. He was born in Franeker, in Friesland, and studied physics and astronomy at the University of Groningen, choosing that school because Jacobus Kapetyn worked and taught there. Since Kapteyn studied galactic structure, it was no great surprise that Oort did so as well.

Oort taught at Leiden University in the late 1920s, and there he discovered that the Milky Way Galaxy rotates differentially, just like our solar system, so that the outer stars move more slowly and take longer to circle the galactic center. He also discovered that there is an outer halo of stars that surrounds the galaxy that moves very slowly indeed. This won him a promotion to assistant director of the Leiden Observatory, which he would later direct.

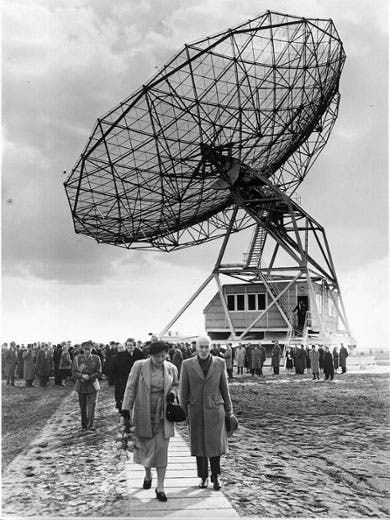

During and after World War II, Oort and some of his students pioneered in building small radio telescopes to "listen in" on the 21-cm wavelength at which hydrogen radiates, first detecting the radiation of interstellar gas clouds, but eventually mapping the Milky Way Galaxy and its "arms", and even detecting radio waves emanating from the center of the Galaxy. Oort is considered one of the pioneers of radio astronomy, along with Karl Jansky and Bernard Lovell. Just last spring we wrote a post on Frank Drake, who in 1959 began looking for extra-terrestrial life, using a radio telescope and searching at the 21-cm wavelength for signals from space.

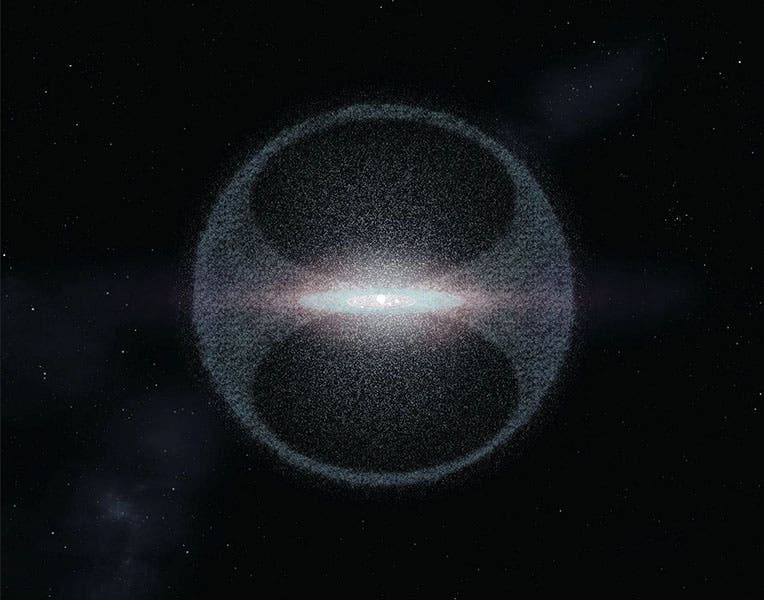

Interestingly, Oort is best known for a hypothesis that has nothing to do with the Milky Way or radio astronomy. In 1950, he published a paper on comets in which he suggested that all comets have their origins in a vast cloud of comet-like bodies – trillions of them – surrounding the Sun, far out beyond the orbits of the planets, and leftover from the formation of the solar system. Occasionally, some of these small aggregations of ice, dust, and gas are disturbed and start to “fall” toward the sun, becoming comets. Oort was led to this proposal because long-period comets, which come close to the Sun on each orbit, lose some of their ice and gas with each passage, so there is no way they could have existed since the origin of the Solar System, 4.5 billion years ago. Consequently, they must be continually replaced from some comet repository. Since many long-period comets go out as far as 20,000 astronomical units, he put the location of his proposed reservoir of comets at this average distance. Since long-period comets can be found in any plane, the reservoir must be a spherical cloud, not a disc.

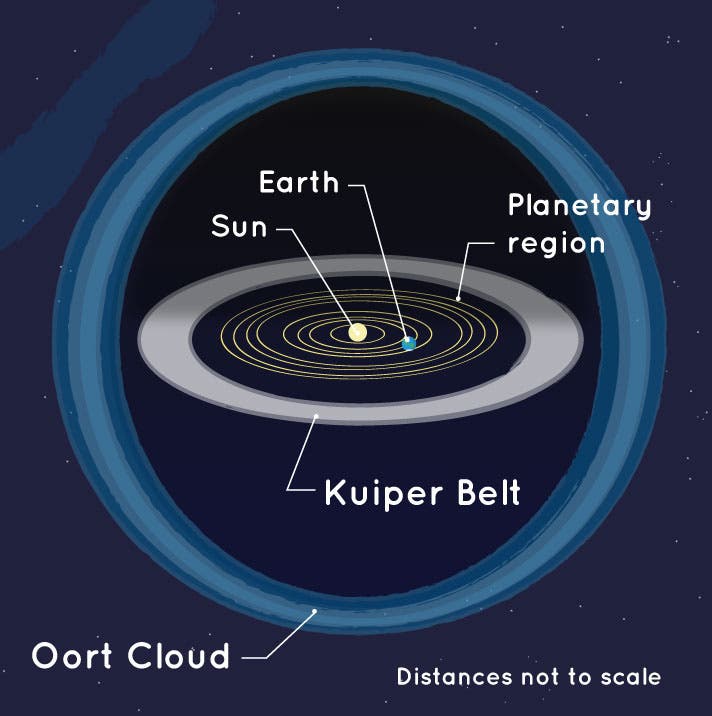

The Oort Cloud, as it is now called, is sometimes confused with the Kuiper belt, the source of many asteroids and short-period comets (and bodies like Pluto), but they are quite different entities. The Kuiper belt is a disc that lies about 50-100 astronomical units from the Sun. The Oort Cloud begins about 400 times further out than the Kuiper belt, is a sphere, and extends all the way into galactic space. I could not find a good online diagram that compares the locations of the Kuiper belt and the Oort Cloud; the image above is the best I could do, and it is woefully out of scale. The existence of the Oort Cloud is impossible to confirm directly, since it is so far away. But no one has found a better way to account for the existence and orbital location of long-period comets, without an Oort Cloud.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.