Scientist of the Day - James W. Abert

James W. Abert, an American soldier, explorer, topographer, and artist, was born Nov. 18, 1820. James' father, John James Abert, was the head of the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers, a new organization formed in 1838 to supervise the mapping of the American West, and J.J. was in charge from the start. The Corps was a unique branch of the Army, because it had no enlisted men, only officers, 36 of them, and every one, I do believe, was a West Point graduate. The younger Abert, James William, joined the Corps in 1843, fresh out of the Academy, and in 1845 he headed out from St. Louis with John Frémont, also a topographic engineer, and already quite a famous western explorer, known as “the Pathfinder.” They were headed for New Mexico, and after that, San Diego and southern California. Abert, however, did not make the California trip – instead he was ordered to explore the headwaters of the Canadian River in Oklahoma.

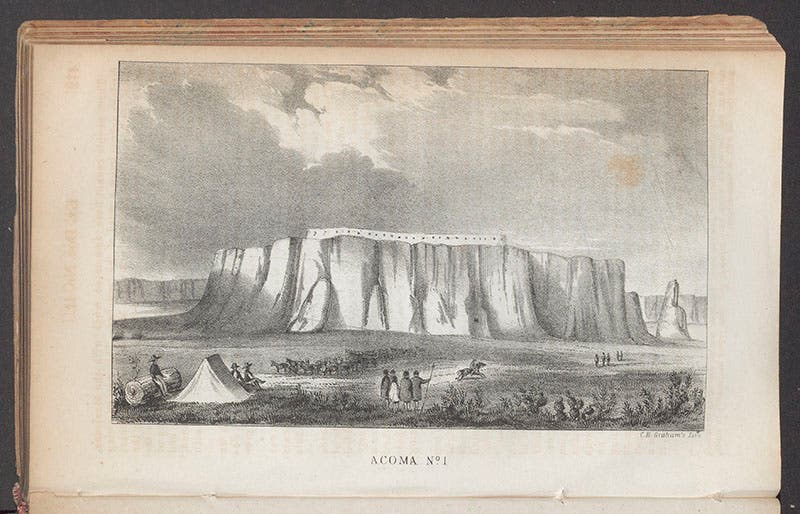

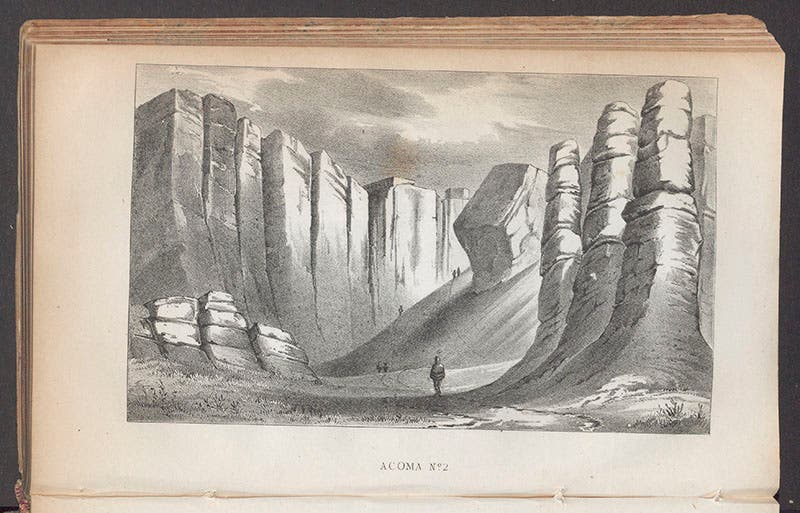

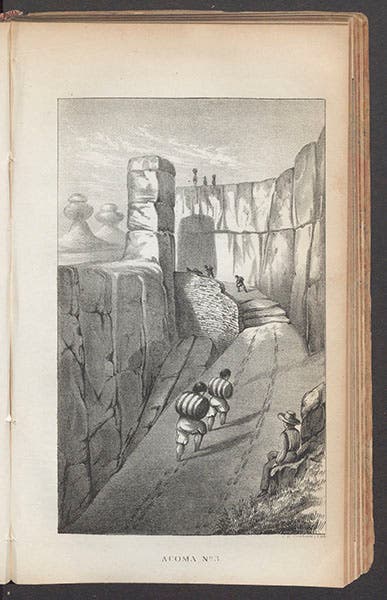

The next year, 1846, he joined the Army of the West, which left Fort Leavenworth in Kansas under General Kearny, off to fight in the Mexican-American War, which had just broken out. Abert’s job, however, was not to fight, but to reconnoiter and map. He was left behind at Bent’s Fort in southeastern Colorado for a considerable time with a life-threatening fever, but he recovered, and once back on his feet, he and another young engineer spent a year travelling through New Mexico. He visited most of the pueblos, including Acoma, Santo Dominigo, and Sante Fe, and being a talented artist, he made sketches along the way, of the countryside, the settlements, and the native Americans. He also paid attention to the flora and fauna, and the geology. Although too young to be an experienced naturalist, he nevertheless managed to discover a few new birds and animals, such as a new species of towhee, and a rodent. We now call them, respectively, Abert’s towhee and Albert’s squirrel.

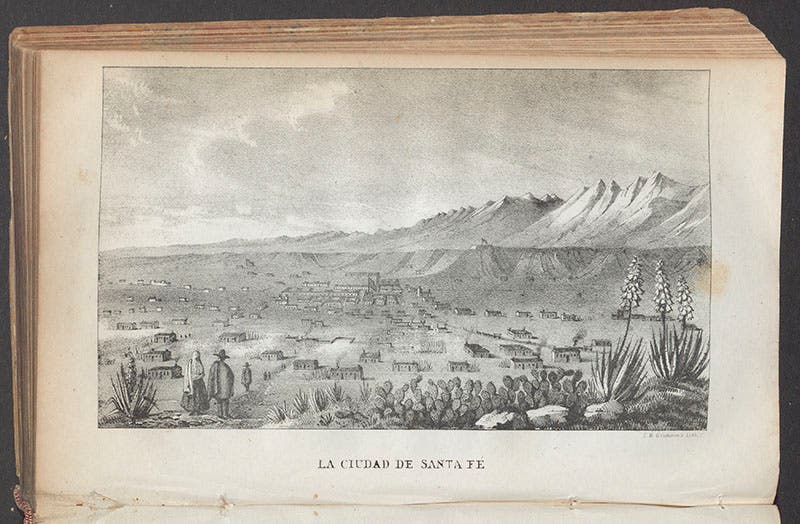

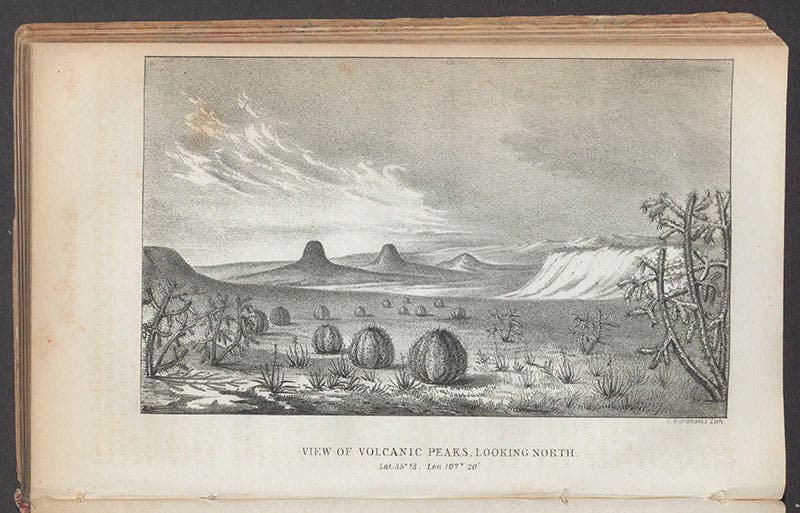

Abert finally made it back to Fort Leavenworth (just barely – he chose to travel across Colorado in the dead of winter), and then to Washington, D.C. to write up his Report of his Examination of New Mexico in the years 1846-'47, which appeared in 1848, wedged in the back of another report, by William Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, the title page of which doesn't even mention that Abert's report follows within. Abert’s is a wonderful narrative, like most of the reports of the adventurous topographical engineers, and his is enriched by what must be twenty lithographs after sketches that he himself drew. We have the Emory/Abert report in our History of Science Collection, and we selected six of Abert's drawings to showcase here. It is hard not to show all three views of Acoma Pueblo – from the bottom of the mesa, on the way up, and at the top (second, third, and fourth images).

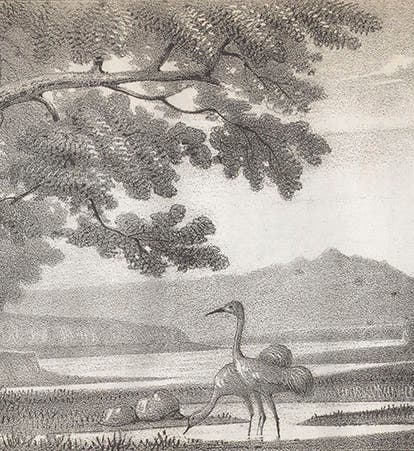

There is a view of a sparse Santa Fe surrounded by army troops that most current residents will find unrecognizable (fifth image). We also find a lovely drawing of the Bosque del Apache that includes several sandhill cranes, which Abert was the first to describe and picture, and which we chose for our lead image. Bosque del Apache is now a National Wildlife Refuge.

We included the Abert/Emory volume in our 2004 exhibition, Science Goes West, but we displayed a plate from Emory’s report, not Abert’s, and you can see why, since it is a pretty spectacular first look at the Saguaro cacti of the Gila area of New Mexico.

Unlike many of his fellow engineers, Abert survived the Civil War, and then lived a long life working at various jobs, including a stint as a professor of English literature at the University of Missouri. He died in Kentucky in 1897.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.