Scientist of the Day - James Smithson

James Smithson, an English chemist and mineralogist, died June 27, 1829, in Genoa. Smithson was born in Paris around 1765, birthdate unknown, the illegitimate son of Hugh Smithson (later Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland) and Elizabeth Macie. The child was named Jacques-Louis Macie; he was not acknowledged by his father. He moved to England while quite young, and his name became James Louis Macie. He went to Pembroke College, Oxford, and received his MA in 1786. While still in school, Macie accompanied Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, a Frenchman, on a geological tour of Scotland and the Hebrides, and actually made the perilous boat-trip to Staffa to see Fingal’s Cave that we talked about just two days ago, in our post on Thomas Pennant. We also published a post on the Hebrides journey of Faujas-de-Sant-Fond.

In the early 1790s, Macie began publishing papers on chemistry and the chemical analysis of minerals. HIs first paper was on a substance known as tabasheer, mysterious pellets found in the joints of bamboo and popular in India as an aphrodisiac and general panacea. Specimens of tabasheer had been sent to the Royal Society by Patrick Russell, an Englishman in India who would soon publish a notable book on snakes. Why Joseph Banks selected Macie to analyze the specimens is not known, but one can guess that Macie must already have had an excellent reputation as a chemical analyst to be so chosen. Macie found that tabasheer is not vegetal but rather a “siliceous earth,” which was a surprise. His paper appeared in the Philosophical Transactions in 1791; we show the first page of the paper (second image). Macie would publish many more papers on similar specific chemical analyses. All papers published after 1801 appeared under the name James Smithson, the name he came to adopt and that is familiar to us today.

Smithson spent considerable time on the Continent, where being illegitimate did not carry quite so great a stigma, and would eventually move to Paris to live. He was often in poor health. When it came time to write his will, which he signed on Oct. 23, 1826, he left all his fortune (inherited from his mother) to his nephew, with the proviso that should his nephew die without issue, the estate should go to the United States to found “a Smithsonian Institution,” "an establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men." Why Smithson chose the United States as a beneficiary is unknown; he had never been to the United States. Perhaps he was just partial to governments born in the throes of revolution – he was certainly sympathetic to the French Revolution. Anyway, Smithson died on this day in 1829; his nephew squandered away his annuity for six years and then died without heirs, and President Andrew Jackson was notified in 1835 that an Englishman unknown to the United States had given its government over half a million dollars to found a national scientific institution in Washington. It took a while for the government to figure out what to do, but in 1846, Congress established the Smithsonian Institution, with Joseph Henry as its first Secretary, and paid the bills with 11 crates of gold coins brought from England. The Smithsonian is now the largest scientific research institution in the world

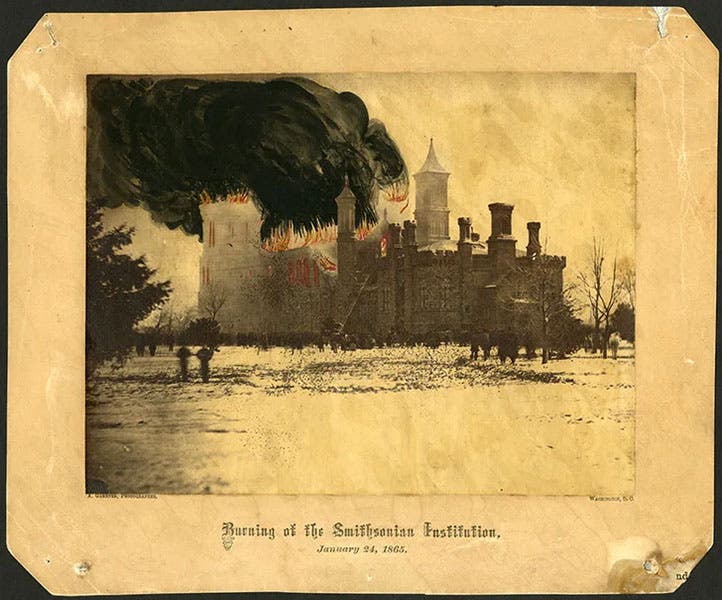

The United States inherited not only Smithson's fortune, but his notebooks, diaries, and personal possessions, which to a modern scholar would probably have yielded a great deal of insight into Smithson's motivations in funding an American institution with English soverigns. Unfortunately, all his personal papers except his library were destroyed in the great Smithsonian fire of Jan. 24, 1865 (third image), so there are many questions about Smithson's life that may never be answered. Fortunately, much can still be ferreted out by a diligent scholar, and that has been done by Heather Ewing, who published, in 2007, The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. It is a terrific book; if you would like to know more about the benefactor who gave us the Smithsonian Institution, there is no better starting point.

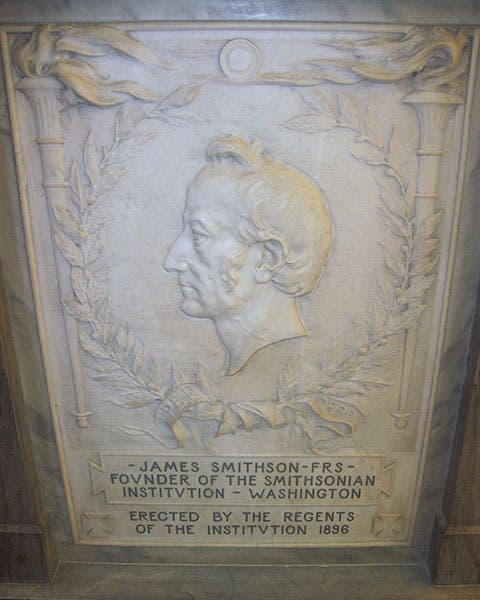

Smithson died in Genoa and was buried there. In 1904, on the occasion of the relocation of the cemetery, his remains were removed and escorted back to the United States by none other than Alexander Graham Bell, and moved into a special crypt in the basement of the Smithsonian Building, where it may be seen today. We show here the memorial stone that is mounted near the sepulcher, and from its date of 1896, we surmise that it had originally been installed by the Smithsonian in Genoa and was brought back along with Smithson’s remains (fourth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.